[Author’s note: I had nearly finished this post in January 2020, but during the ensuing pandemic chaos, I pushed it aside until now. This is essentially a pre-COVID time capsule, though I’ve added a post-COVID epilogue.]

A few years ago, I underwent peer evaluation of my teaching as part of a reappointment review. While being observed by a colleague, I was quite thrown off my game as he frequently stood up in the back of an auditorium full of seated students. I was baffled about what he was doing. Later, he explained that he was standing to see how many students were using their phones. Most of them, apparently. How did my course arrive at this point?

This was my first time teaching this large course (175 students) that I took over from a colleague. I felt prepared, but my focus was consumed by keeping pace with the next lecture or lab while also teaching another new course. I was pleased with how this course went overall, and the student evaluations were solid (though not exceptional). However, that comment about the phones stuck with me. Aside from some small tweaks, what I really wanted to improve was the course atmosphere. The phone use was a symptom of limited engagement by my students.

After that term’s conclusion, I read Ken Bain’s amazing What the Best College Teachers Do and James Lang’s Small Teaching. Both emphasize the importance of setting a course’s tone immediately. In that first term of teaching the course, I had actually thought about this. I began the first class session with:

- A talk on effective learning strategies (unsurprising to readers of this blog)

- Handing out and walking through the syllabus, emphasizing how the course was very deliberately designed (e.g., clickers, online checkup quizzes) to support effective learning strategies

This was not an unreasonable approach, but I was missing two key ingredients. The first, emphasized in Bain’s and Lang’s books, was activating students’ curiosity. My brief outline of the topics to be covered and a summary of the syllabus was not exciting in any way. It didn’t grab students’ interest. It didn’t make them think. Another issue in the course was limited student interaction, especially with one another. The students in my course are very diverse. Roughly two-thirds are from Canada or the US and one-third from other countries, but students typically cluster with classmates sharing similar backgrounds. This challenge is much larger than my course, but I wanted to foster better interaction among my students.

Round 2

One beautiful thing about teaching is that you get a fresh start each term. In the following year, the students didn’t know me (except perhaps as the nerdy guy in the plant ID videos they had seen), and they didn’t have much of an idea of what our course would be like. I had a new chance. I tried several new approaches to make the course more engaging.

Focusing on the Big Picture

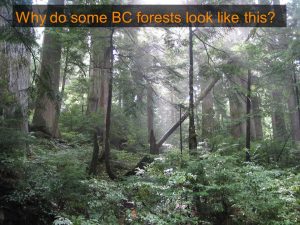

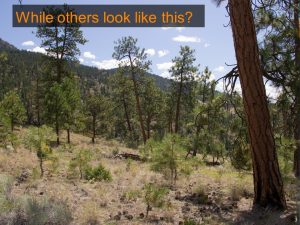

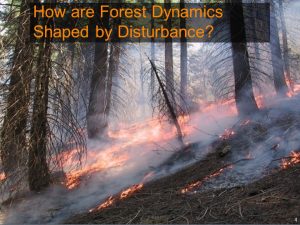

In my opening class, I mentioned the syllabus only in passing. I had posted it online, but I didn’t hand it out or go over it that day. Instead, I started with the big picture, as suggested by Bain and Lang. My first slide simply asked, “What is this course about?” I followed that with a number of photographs, each posing one of the broad questions we would seek to answer. I didn’t address these questions. I simply read each one and paused for a moment in hopes of piquing students’ curiosity.

Student Interaction

It is very possible for a student to sit next to the same person for an entire term and never once interact. My hope is that students who feel less anonymous in class will be more engaged. In that first class, I told them that even though this is a large course, I didn’t want it to feel passive or anonymous, and I wanted them to meet new classmates. I asked students who were from Canada or the US to raise their hands, then non-US international students. It was again about two-thirds to one-third with pronounced clustering of these groups. I gambled. I asked the Canadian/US students to stand, pair up with someone they didn’t know, find a non-US international student they didn’t know, and then all sit back down together. I was afraid students might balk, but they were game (as they often are at the start of a term). They didn’t all end up in groups of three like I had asked, but the lecture hall was thoroughly reshuffled, and I could overhear most students introducing themselves to new classmates. Once in those groups, I asked them to collaboratively write down the themes, concepts, and ideas that they remembered from the prerequisite course. Having just introduced the big questions of my course, I wanted them to activate the related knowledge they had gained last term (and I wanted them to have a low-stakes chance to engage with their new classmates).

Offering a Stake

Faculty sometimes gain student buy-in in a course by ceding some control to students. For example, students might be allowed to individually choose the relative weighting of exam and project grades, within bounds. Though I’m intrigued by that idea, I didn’t think I could handle the grade-calculation logistics in a large course (at least not while using the Canvas grade book). There are two areas, though, where I was interested in student input, a late-homework policy, and a classroom electronics (laptop) policy. After giving some background on these topics, I asked students to discuss in their groups and then give me a few suggestions. We didn’t finish before time ran out, so I asked them to sit in these same groups the following class so we could wrap up our discussion. I subsequently implemented the consensus suggestions on both of these policies.

Removing Spatial Barriers (and Anonymity)

The first time I taught this course, I remained almost exclusively at the front of the auditorium. Though I moved around and rarely stood behind the lectern, I never walked up the aisles. I made two changes this second year. First, I used the microphone. It was a wireless lavalier mic, allowing me to freely wander. Second, I roamed the entire auditorium, both while I was speaking and especially while students were engaged in small-group discussions. I hoped that reducing this physical distance would make students feel more involved in class and less like passive observers of a performance at the front of the room. I think some students were also more likely to remain on task if I was periodically near them, rather than always separated by 12 rows of seats.

The Results

I was honestly shocked at how much more engaged the students were the second year. When I asked them to discuss a question with their neighbor and I wandered the room, 95% of them were actually discussing the question. Though some students were obviously disengaged, their numbers were low and off-task electronics use didn’t seem to be a major issue. No doubt some of this simply reflected me being more comfortable with the course the second time around, but I also think those small changes noticeably improved student engagement.

Epilogue

In the 18 months since I first drafted this post, I have continued to use similar strategies, though online teaching during the pandemic has been challenging and added even more barriers to student engagement, but that is a topic for another day. As I write now, the upcoming term is still scheduled to be primarily in person, but sharply increasing case counts are adding uncertainty. I’m hopeful things will turn around soon and we will be able to teach in person. The broad points of this post still stand, but as we return to the classroom, the atmosphere will certainly be different and we will need to be sensitive to the anxieties of students (and faculty). I think many of us are craving interaction after a year of only digital connection. Adaptability and compassion for our students will be key.

I further reflected on the “Big Picture” concept this past spring, when I participated in the Best Teachers Institute, an online workshop series hosted by Ken Bain (and including guest appearances by James Lang, among others). In one of the early sessions, Bain brought up the idea of motivating students by presenting big questions at the start of a course. He posed three thought-provoking questions for instructors to ask ourselves about the courses we teach:

- “What’s the biggest question that my course will help students begin to address?”

- “How will I address that question in a way that will engage students?”

- “What kind of language will get them to see that question as important, intriguing, and beautiful?”

That’s a tall order, and I don’t think I’ve fully achieved this framing in any of my courses, but these are the questions we should be asking ourselves as we prepare for the coming term. It is a new chance to make first impressions.

References

Bain, K. (2012). What the Best College Students Do. Belknap Press: An Imprint of Harvard University Press.

Lang, J. M. (2016). Small Teaching: Everyday Lessons from the Science of Learning. John Wiley & Sons, Incorporated.