The final exam for my Strategy & Politics class always takes the same form: I ask my students to apply what they have learned about game theory and parliamentary history to make sense of a contemporary political controversy. The topic of this year’s exam was the partisan machinations around the Canadian Senate, that is, 1) the Conservatives’ threat to deploy their (temporary) Senate majority against the government’s legislative program, and 2) the Liberals’ promise to reform the Senate by installing non-partisan Senators via a “merit-based” selection process. Will the Conservatives’ erect a Senate roadblock, and will the Liberals then break their promise and stack the Senate with Liberal hacks? Or are both sides more likely to compromise, with the Conservatives passing duly diluted Liberal legislation through the Senate?

I always write up a template answer to the Strategy & Politics final exam that I give my students, and with the House’s attention now on Senate Reform, here’s my answer to my own question:

The Conservatives have threatened to use their Senate majority to stall the Liberals’ legislative program. (OK – they have toned down this kind of talk recently.) The Senate has the constitutional power to veto all legislation save that which is financial in nature. Furthermore, the Conservatives enjoy a majority in the Senate. To that extent the Conservatives’ threat is not an idle one. However, as Table 1 below shows, there are 22 vacancies in the Senate. Were Prime Minister Trudeau to fill these vacancies with loyal Liberals, the Conservative majority would vanish. But the Prime Minister has promised not to do this; instead, he proposes to appoint Senators on the basis of merit as recommended by a non-partisan board. Adding to the complexity of the situation is the fact that while in opposition Trudeau expelled Liberal Senators from the Liberal caucus. This implies that Liberal Senators are not bound by party discipline. Common ideological preferences may well lead many Liberal Senators to vote the party line, but it cannot be guaranteed.

Table 1. Party Standings in the Senate

| Party | N Seats |

| Conservative |

45 |

| Ind. Conservative |

1 |

| Ind. Liberal |

28 |

| Independent |

9 |

| Vacant |

22 |

| TOTAL |

105 |

I consider 3 questions in light of this situation: 1) How can the Conservatives be expected to deploy their Senate majority? 2) How is the Government’s proposal likely to alter the situation? 3) Are the Liberals likely to follow through on their merit-based appointment process?

1. How can the Conservatives be expected to deploy their Senate majority?

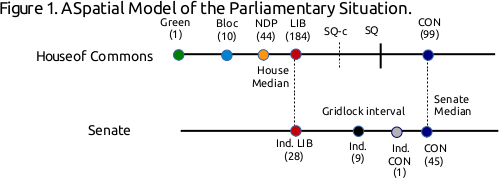

I use a a spatial model the parliamentary situation to understand how the Conservatives can be expected to deploy their Senate majority. Figure 1 depicts the distribution of parties along the left-right spectrum in both the House and the Senate. I assume that the parties are all perfectly cohesive (so a single ideal point suffices to represent the preferences of party members), and that parties’ respective positions are identical across the House and Senate. I also assume that the 9 independent Senators share an ideal point midway between the Liberals and the Conservatives; this will be a useful simplification. Actors have Euclidean preferences.

The Liberals enjoy a majority in the 338-seat House of Commons, and hence the median voter in the House is a Liberal MP; measures pass the House only with the support of this Liberal MP (i.e., the House median). Similarly, the median voter in the Senate is a Conservative; measures pass the Senate only with the support of this Senator (i.e., the Senate median). Policies in between the House and Senate medians cannot be moved. To appreciate this, consider the status quo policy, SQ, in this interval: if the Liberals try to replace SQ by an policy at their own ideal point, the Conservatives can use their Senate majority to veto the move; the policy will therefore remain at SQ.

The Conservatives cannot arbitrarily exercise their Senate veto. The Senate is an unelected body, and as such it lacks legitimacy among the Canadian electorate. To use it to veto every Liberal bill would allow the Liberals both to paint the Conservatives as obstructionist and to build a case to bypass the Senate (e.g., by abolition). I model this by assuming the Conservatives pay a cost, c > 0, for exercising their Senate veto. This cost creates an “envelope” of ±c around any status quo policy within which the Liberals have discretion. For example, were the Liberals to replace SQ by any point between SQ-c and SQ, the Conservative would allow it to pass because the cost of vetoing any such policy would exceed the gain associated with keeping policy at SQ.

The model highlights that the parliamentary situation is defined by a key relationship between two variables, the ideological distance between the Liberals and Conservatives, |LIB-CON|, and 2) c, the cost to the Conservatives for exercising their Senate veto. In particular, the Conservatives’ incentive to veto Liberal bills is strong only if they perceive the cost of deploying their veto to be small relative to the distance between their ideal point and the Liberals’, i.e., c << |LIB – CON|. Under opposite conditions, (i.e., c >> |LIB – CON|), the Conservatives would rarely have an incentive to use their Senate veto.

2. How is the Government’s proposal likely to alter the situation?

The reasoning above identifies conditions under which the Government’s proposal to appoint Senators on merit rather than partisanship is moot, i.e., c >> |LIB – CON|. The interesting case is one in which the Liberals’ and Conservatives’ positions are far apart, and Conservatives perceive the cost of a veto as quite small. Let’s assume that these more interesting conditions obtain.

Even so, how the Government’s proposed appointment process is likely to alter the parliamentary situation depends critically on the ideological distribution of meritorious individuals. Consider two reasonable possibilities: 1) that meritorious individuals are as likely to be left-wing as right-wing, or 2) that meritorious individuals are – in Canada, at least – likely to be left-of-centre in their ideology. These two situations are depicted in the top and bottom panels of Figure 2, respectively. The bell-curves in the panels reflect the (normal) ideological distribution of meritorious individuals, the set of people from which a putatively non-partisan board would select Senate appointees. For simplicity, the distance between the Liberals and Conservatives is scaled to be two standard deviations of this same ideological distribution.

Figure 2. Possible ideological distribution of meritorious individuals

What would be the effect of 22 non-partisan appointments were the ideological predisposition of those appointees as depicted in the top panel of Figure 2? Under such conditions one would expect approximately 3.5 appointees would hold positions to the Conservatives’ right.1 The Conservatives’ could expect the regular support of such individuals. Another 7.5 appointees could be expected to hold positions between the ideological centre (at 0) and the Conservatives’ position. The Conservatives would require the support of just 3 to 4 of these individuals to maintain a majority. The Senate median would therefore shift to the left under these conditions, but not by much; it would fall about midway between 0 and 1.2 Furthermore, the occasional defection of even 1 or 2 Liberal Senators (who, recall, are not under party discipline) would also dilute any leftward shift in the Senate median.

The bottom panel of Figure 2 depicts a situation where most meritorious individuals are to the left-of-centre. This is effected by shifting the ideological distribution of such people to the left by 1/2 standard deviations. As a consequence, the Conservatives could expect at most one of the 22 appointees to fall to their right, and only 5 such appointees would hold positions between 0 and 1. Thus at most 51 Senators (including the independent Conservative) would hold positions to the right of 0; the Senate median would thus fall just to the left of centre.

We are now in a position to answer the question set out above, that is, how will the Government’s proposed appointment process alter the parliamentary situation. The general answer is that it will shift the Senate median to the left – but by how much depends on the ideological distribution of meritorious individuals (and, to a lesser extent, on the cohesion of the Senate Liberals). If potential appointees are as likely to be right-wing as left-wing, the impact on the Senate median will be minimal; if most such individuals are left-wing, the Liberals’ appointment process may move the Senate median much closer to the Liberals’ position. However, the small number of Liberal Senators does put a limit on how much change the Liberals can effect in this way. Even if the ideological distribution of meritorious individuals were heavily right-skewed such that all 22 appointees were to the left of the Liberals, there would still only be 50 Senators at or to the left of the Liberal position, not enough to push the Senate median to the Liberals’ position. But the Liberals do not require that; to effect their agenda they simply require that the distance between the Senate median and their own position be less than c.

3. Are the Liberals likely to follow through on their merit-based appointment process?

The model establishes conditions under which one can expect the Liberals to break their promise to effect a truly non-partisan, merit-based appointment process.

- c ≥ |LIB-CON|: it is costless for the Liberals to keep their promise because they can effect their legislative agenda regardless of the Conservatives’ Senate majority. Under these conditions, the Liberal proposal for Senate appointments is mere window-dressing.

- c < |LIB-CON| and the ideological distribution of meritorious individuals is symmetric: The Liberals are likely to break their promise under these conditions. This is is because a non-partisan, merit-based appointment process will leave the Senate median close to the Conservatives’ position, allowing the Conservatives to block much of the Liberal agenda. The smaller c is relative to the ideological distance between the two parties, the stronger the incentive for the Liberals to stack the Senate, either overtly or covertly by politicizing the “non-partisan” appointment process.

- c < |LIB-CON| and the ideological distribution of meritorious individuals is right-skewed: The situation is unpredictable. On one hand, by simply keeping their promise, the Liberals would be able to effect a significant leftward shift in the Senate median. If the resulting distance between the Senate median and the Liberals’ position was then less than c, one could expect the Liberals to keep their promise because even a non-partisan appointment process would enable them to effect their legislative agenda. However, were the resulting distance between the Senate median and the Liberals’ position to still be greater than c, the Liberals would likely break their their promise and stack the Senate provided they felt that they could count on the unwavering support of both sitting Liberal Senators and their “non-partisan” appointees.

1Given 22 appointees and a .16 probability that an appointee would hold a position at or to the Conservatives’ right, one would expect 3.5 appointees to hold positions at or to the Conservatives’ right.

2In fact, one can use the normal distribution to compute that the Senate median would fall at .45 standard deviations to the right of 0.

Follow

Follow