Foolish Addendum in Response to Sztulwark

(With many thanks to Ana for organizing the series)

By George Allen, PhD student at the University of California, Irvine

The radical restructuring of the economy towards neoliberalization in the past 40+ years altered the governance of relationships, conduct, self-awareness, values, and feelings. Neoliberal rationality attempts to create a normative subjectivity that is individually responsible for material subsistence by equating the value of individuals and institutions with market rationality, “Because neoliberalism casts rational action as a norm rather than an ontology, social policy is the means by which the state produces subjects whose compass is set entirely by their rational assessment of the costs and benefits of certain acts” (Wendy Brown). Precarity is rationalized and normalized by the dissemination of market logics into every sphere of life, often under the aegis of ‘personal responsibility’.

One of the features of neoliberalism is the way that vocabularies have been co-opted, or as Alessandro Fornazzari writes, “one of the characteristics of post-dictatorship Chile is that the boom in memory becomes undistinguishable from the boom in forgetting”.

With this in mind, in his article “¿Dónde están los amigos y las amigas?” Diego Sztulwark writes emphatically,“¡Manipular los enunciados teóricos para hacerlos funcionar de modo tal que sea la propia vida la que reciba orientación! El amateur apasionado es la versión bricoleury activista del sujeto del poema. Es el militante buscando los medios de darse nuevas posibilidades de vida.” Sztulwark finds “nuevas posibilidades de vida” of subjects becoming non-subjects or non-subjects qua becoming, qua friendship, qua militant readers and amateur bricoleurs.

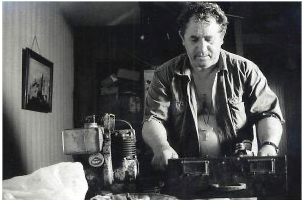

Sztulwark summarizes these theorizations under the banners of a ‘transfiguración perservante’, ’ejercicios espirituales,’—or, put in the language of Colectivo Situaciones, “describir mutaciones subjetivas, y participar de una imaginación política capaz de proyectar formas diferentes del hacer-pensar colectivo” (similarly, Veronica Gago uses the term ‘pragmática vitalista). This line of thinking apropos Fornazarri’s point asks us to think beyond “what is lost?” towards “what is emerging?”. One answer to the latter can be found in the Argentine film Mundo Grúa which tells the story of Rulo, a rotund underemployed handyman–in and around 2000–training to work as a crane operator on a Buenos Aires high-rise. The film questions the language of melancholia—in the neoliberal context—as exclusively contestatory, in favor of documenting a differentiated field of emergent and materializing exhaustion. It utilizes a number of neorealist techniques such as onsite shooting, long takes, deep focus shots, and a cast of non-professional actors—techniques often associated with a representational fidelity to marginalized subjects, repressed histories, and alternative production models that reflect a commitment to social justice. However, the film undermines ‘realist’ aesthetic tendencies with irrational cuts that make characters distant and complicate spatial transparency while at the same time using an observational style not unlike documentary. Film scholar Joanna Page reads this blurring of aesthetic styles as a “provisional form of (auto)ethnography” that seeks to deconstruct the relationship between visibility and knowledge. Writing on the absence of character POV shots in the film, Page argues “As spectators we are denied knowledge of what Rulo is able to see; this technique works to undermine conventional processes of identification” (51).

The appropriation or the faithful mis-reading of texts ala Sztulwark implies a nomadic, fugitive, de-colonial, and anti-institutional movement. However, there is something unsettlingly comfortable about this vision of bricolage, dis-identification, and discontinuity. What kind of consequential choices are left (and what choices does this approach leave us with) to make in a society where commodification, consumer consumption, and capitalistic disjunctive and unequal expansion is the norm? Do the micropolitics of becoming no-neoliberal steer us away from thinking the (re)structure of society? Put differently, what is the congruence of Sztulwark’s redemptive figure of the bricoleur, the friend a venir, the nomad—assemblers for the purposes of disjunction and in the process of dis-identification—with the unequal and discontinuous expansion of capital? Ricardo provides some eloquent thoughts on this.

These structures of relations seek to avoid the fundamental mistake of the Lacanian ‘fool’ who believes in his immediate identity—unlike Zuangh Zi who wonders if he is Zuangh Zi dreaming of being the butterfly or the butterfly dreaming he is Zuangh Zi, the fool believes his identity is his property, not defined by the material and symbolic relations that subtend it. In other words, the ‘fool’ is not far from the psychotic and the narcissist who deny and disavow any mediation of identity. However, even as non-fools, we are the consciousness of the dream–the Lacanian gaze is that which colors Zhuang Zi’s dream. To what degree is Sztulwark’s redemptive reader-bricoleur, friend a venir (etc.) colored by the fantasy of disjunction and the reaction against neoliberal injunctions?

To return briefly to film: Furthering Page’s argument in the vocabulary of Sztulwark, we might say that Mundo Grúa performs an aesthetic coaching, but does not confirm Diego’s ‘ontological optimism.’ Rulo, Mundo Grúa‘s protagonist, is the bricoleur par excellence, but his efforts to assemble and re-arrange the detritus of his lifeworld are constantly thwarted. In one scene, Rulo stops and expresses his admiration for a large film projector. The implications are clearer than they may first appear. Rulo the repairer is fascinated by the smooth-functioning projector just as he views the crane as a space of free-movement. However, Mundo Grúa shows both to be idealistic fantasy spaces, unattainable for and unrelated to Rulo and his lifeworld. On the one hand then, we should reiterate Page’s argument to read the film as anti-representational in the sense that film can not provide direct depictions of life, capital, space, etc. But, it is important to emphasize the way Mundo Grúa, at the aesthetic level, interrupts rather than smoothes and synthesizes depictions through neat cross-cuts. The gambit of Mundo Grúa is one of filmic dysfunction and repair in opposition to the smooth-functioning spaces of commercial cinema.

To return briefly to film: Furthering Page’s argument in the vocabulary of Sztulwark, we might say that Mundo Grúa performs an aesthetic coaching, but does not confirm Diego’s ‘ontological optimism.’ Rulo, Mundo Grúa‘s protagonist, is the bricoleur par excellence, but his efforts to assemble and re-arrange the detritus of his lifeworld are constantly thwarted. In one scene, Rulo stops and expresses his admiration for a large film projector. The implications are clearer than they may first appear. Rulo the repairer is fascinated by the smooth-functioning projector just as he views the crane as a space of free-movement. However, Mundo Grúa shows both to be idealistic fantasy spaces, unattainable for and unrelated to Rulo and his lifeworld. On the one hand then, we should reiterate Page’s argument to read the film as anti-representational in the sense that film can not provide direct depictions of life, capital, space, etc. But, it is important to emphasize the way Mundo Grúa, at the aesthetic level, interrupts rather than smoothes and synthesizes depictions through neat cross-cuts. The gambit of Mundo Grúa is one of filmic dysfunction and repair in opposition to the smooth-functioning spaces of commercial cinema.

Pensar desde la crisis no es pensar sobre la crisis. Hay, al menos para mí, un saber desde la crisis que es similar a la suspensión —o el paso hacia atrás— de la infrapolítica, a la exposición de la inestabilidad de cualquier verdad fundacional de la anarqueología, a la imposibilidad de nombrar el cambio o el régimen consecutivo en el momento de interregnum y a la semiótica de la contrapedagogía de la crueldad. Este saber radicaría en eso que Diego Sztulwark llama experiencia plebeya, que “no es la revolucionaria, porque no supone ni da lugar a una política específica, aunque sí involucra una relación explícita y desprogramada con la propia potencia, una indecibilidad de su propio lugar en relación con la axiomática del capital” (57). Así, si la existencia (y la vida) para pensarse debe(n) dar un paso atrás, no llenar los huecos del pasado compulsiva e inquisitorialmente, dudar de someterse a la fuerza del capital, desconfiar terriblemente del estado, pero también apostar por uno que sea restituidor, se debe a que sólo dentro de la sensibilidad plebeya es posible ver formas de vida que desbocan la “razón” del estado y la paranoia del capital. La ofensiva sensible: neoliberalismo, populismo y el reverso de lo político de Diego Sztulwark ofrece, quizá, uno de los aportes más interesantes para repensar el excedente de vida (y muerte), de potencia y de deseo que ha dejado el neoliberalismo en su producción de subjetividades en América Latina (por su puesto, claro, con énfasis en la historia moderna y reciente de Argentina).

Pensar desde la crisis no es pensar sobre la crisis. Hay, al menos para mí, un saber desde la crisis que es similar a la suspensión —o el paso hacia atrás— de la infrapolítica, a la exposición de la inestabilidad de cualquier verdad fundacional de la anarqueología, a la imposibilidad de nombrar el cambio o el régimen consecutivo en el momento de interregnum y a la semiótica de la contrapedagogía de la crueldad. Este saber radicaría en eso que Diego Sztulwark llama experiencia plebeya, que “no es la revolucionaria, porque no supone ni da lugar a una política específica, aunque sí involucra una relación explícita y desprogramada con la propia potencia, una indecibilidad de su propio lugar en relación con la axiomática del capital” (57). Así, si la existencia (y la vida) para pensarse debe(n) dar un paso atrás, no llenar los huecos del pasado compulsiva e inquisitorialmente, dudar de someterse a la fuerza del capital, desconfiar terriblemente del estado, pero también apostar por uno que sea restituidor, se debe a que sólo dentro de la sensibilidad plebeya es posible ver formas de vida que desbocan la “razón” del estado y la paranoia del capital. La ofensiva sensible: neoliberalismo, populismo y el reverso de lo político de Diego Sztulwark ofrece, quizá, uno de los aportes más interesantes para repensar el excedente de vida (y muerte), de potencia y de deseo que ha dejado el neoliberalismo en su producción de subjetividades en América Latina (por su puesto, claro, con énfasis en la historia moderna y reciente de Argentina). Thanks to everyone who took part in last week’s discussion. It was, I thought, a very useful conversation about Diego Sztulwark’s book,

Thanks to everyone who took part in last week’s discussion. It was, I thought, a very useful conversation about Diego Sztulwark’s book,  Thanks to everyone who took part in this week’s discussion. It was great to have more new people joining us, this week from California and the mines of New Mexico.

Thanks to everyone who took part in this week’s discussion. It was great to have more new people joining us, this week from California and the mines of New Mexico.