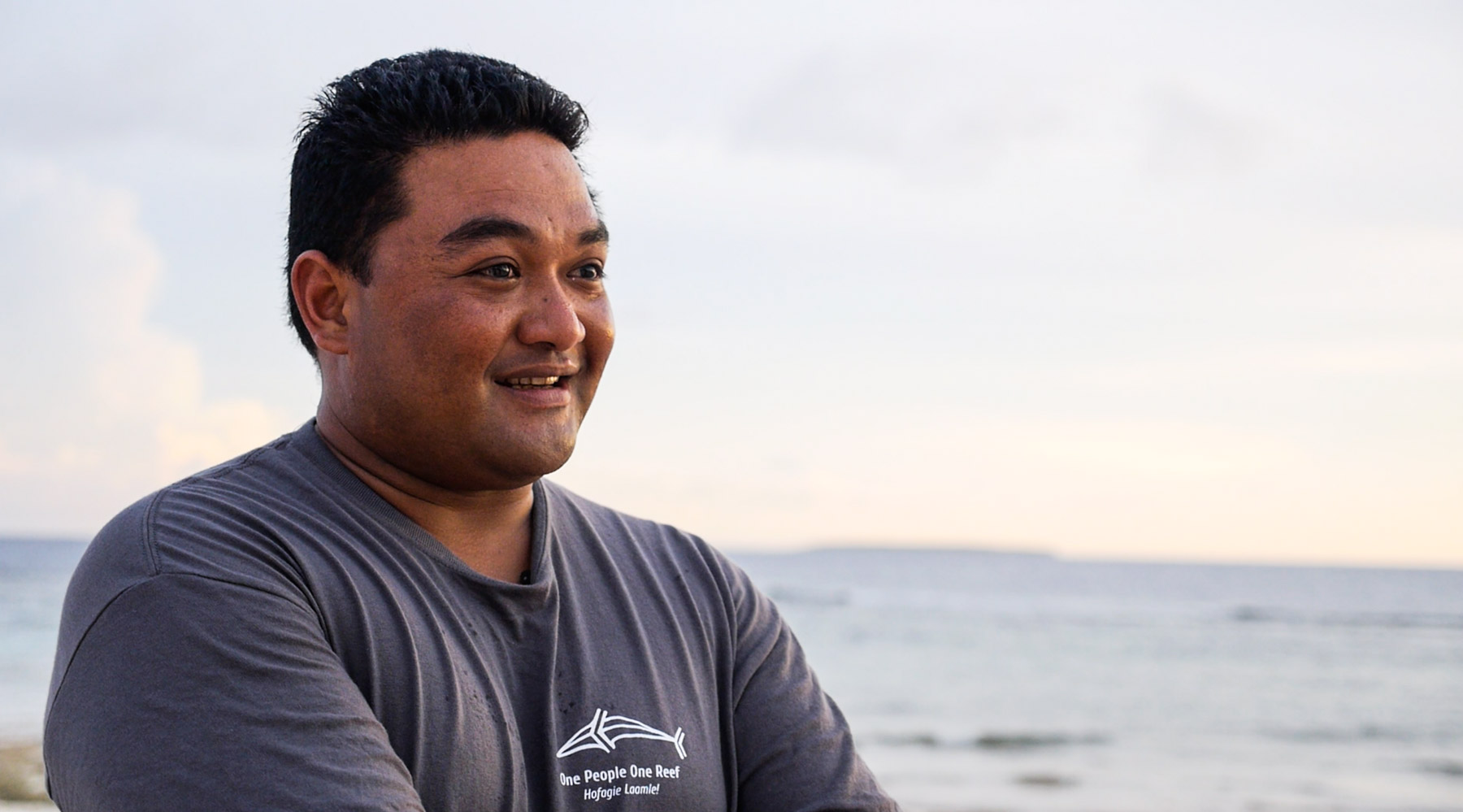

Junior is a community leader and organizer from the Ulithi Atoll. He was on the island of Falalop during the storm.

When I first heard about the storm, I was at the priest’s house, we were talking about renovation of the church or something, and the radio call came in. This was April … No. It was on a Friday, because somebody had mentioned on the radio to look out for this small dot brewing in the east, that seemed to follow the path of previous strong typhoons. This was way back in the Chuuk area, it started out very low latitude. It means that it’s going to go North, moving West, somewhere in the path. That’s where I was, on the beach, hearing that.

I went to my house to look at the chart, and what really helped me to push for preparation, there was a typhoon from 1991 that my father had plotted on this same chart. This was a ’91 storm that had started off the same area, he had plotted this thing all the way past Ulithi. I looked at that and I was like, “Oh wow,” you know? If this followed that same path, it would run directly over us.

That really helped. I used that to convince the community that we’ve seen that before, we’ll see it again. The elders got involved, and a couple of guys with radio access, and we started to monitor from that time on. This became the Saturday after, actually.

First we had a meeting with the community. The first one was Sunday, by Saturday evening (Sat at 3:00), we had done the Friday, Saturday monitoring directly with Guam. We see that it’s continuing to follow the same path, it continued to intensify. At that point, the decision was made to bring the community in. The first meeting was actually Sunday after mass, to prepare. This is at the point where we identified the shelters, just talking about it, how we’re going to prepare and get the word out. The actual cutting of coconut trees happened on Monday.

We cut down a total of 26 coconut trees. All the boys got together and we started from one end of the island. We cut down all the coconut trees that seemed to be on top of buildings with people in them. Some we didn’t. We went house to house, all the way to the end of island, going to each family and asking if there’s things we wanted moved. Particularly we cut down the trees that seemed to be in the way to hit houses, and then check on if there was loose tin or things that could be dangerous if they were flying. Two things were the main focus of that particular preparation, it was if there’s tins that are loose you put them in a pile somewhere and then put heavy objects on top. We did that at almost all the houses, especially the ones with the elders. Basically just going around, while we were doing that, we were informing people to put away their pots, all of the water catchments should be fixed. It’s starting to look funny at that point, wind-wise. There’s no rain, so we had informed people that by the next day, it’s starting to rain and not too windy, people should start to collect their water and then cover it eventually. We were aware of that by Monday.

We had got together with the leaders and decided on what kind of warning we should give out. That Sunday, the peace corps office was calling for me to bring them to Falalop and bring them to the lodge. Eventually between 12 and 2, the decision was made to move all the peace corps out of Ulithi, so we just had to wait for one more from Federai and then send them out that Sunday. They were out of the way, and then we focused on the locals. At 1:00, we had the last plotting of the storm. And then the decision was made to shut down power by 6:00. Secure our plan, and shut down.

We shut down the power way before the shelters were shut. We shut down the power, we secured the power plant and the equipment, and then everyone’s out of the working places, the school and all of that. I think it was 1:00 in the afternoon that everyone was stopped and everyone went home to fix food or get ready for the storm. By 6:00, everyone was in the shelter. It’s still daylight, the wind is starting to pick up a little bit but it was totally fine, normal.

I was in my house on Falalop, one of the shelters, with 29 other people, and most of the babies were sent to my shelter. I guess that there’s some trust in there, to have the kids. The kids were all sent together to send them to one of the safest places, and a lot of them are related to me. Most importantly, we were the farthest in and there’s some backup water in my area, so they figured that would be helpful, thinking that the storm was going to be that bad. There was some indication that we were going to be hit pretty bad.

Then we had a head count at 6:00. What shelters had people, and making sure that all the main ones, all the VHF communication [walkie-talkies] was established to everyone. There’s a few concrete houses, they’re on our side, they’re closer to me but they didn’t have VHF communication.

VHF communication is the radio that we used throughout the whole storm. We stayed in communication the whole time, all the way through the next morning actually.

For me, by 8:30-ish, my porch went. The whole thing came off. I figured, we had plotted the storm and estimated that that closest point of approach would be about 10 to 11, if it follows the path and moves at the same speed that it was going. It actually slowed down, I thought, or maybe because we were in it, it just felt like forever. By 8:30, the first part of the house went off. That porch that we lost at my house, that’s where I store all of the propane gas and the gasoline. That was kind of the thing on my mind, that it would catch on fire. I wasn’t too worried about the house collapsing or any of that (it’s concrete). I figured we’re so far up in the middle of the island, if that’s gone, everything is gone. I think I was more worried about the propane and gasoline that had flown off, and we’re starting to feel the hits from that side of the house.

The next thing I thought about doing was, how are we going to get these babies out of here? At one point, I want to say 10 – 11ish, we had wrapped up the youngest baby, that was three months old, and put her inside the highest shelf inside my room, thinking that, if we go, she’s the last to go.

The only access out at this point because we had boarded up the house was going to be out through the bathroom in the back. We moved everyone back telling them because it was safer, but really we wanted to keep them away from the side with the gasoline. something had flown by and hit one of the big drums open so we could smell the gasoline inside at this point. We kept telling the girls that there was a leak, that my stove when it’s windy, the propane gas, you can smell gas. No, that was completely made up just to keep calm in the shelter.

I think for me, the toughest point was that. We were aware of the danger, we could barely breathe because the pressure was so low. First time I’d experienced something like that. You could feel the pressure so low, it feels like you were diving at 80 feet. That was something that was different from other storms.

The biggest thing was how to get these kids out of here if it blows. That was the biggest thing for me. You look outside and you see the lightening. Every time it lights up, you see a different landscape. Whether it’s a tree, it’s different house, or so much of whatever. Moving out into that big open line of mine, you could see that. that’s an image that’s probably going to be stuck in my mind forever.

I took a video on my phone because I thought that was the end of all of us. I took a video and put my phone in a dry bag with my ID and my wallet. I thought, “This is going to float and somebody’s going to find it.” To give them an idea of what it was like during the storm. I wasn’t thinking at all about, if we take this picture here, more people will see this. I wasn’t thinking too much about how it was going to be seen, I just thought, let me give people an idea of what’s going on here at this time. I was afraid that anything could happen and … I just took that part and with my passport, my ID, and my wallet, I rolled it up with air in it and carried it with me during the whole storm.

Here’s the video that Junior took on his phone during the storm:

We weren’t able to go to sleep. At about 11:45 we got the call. We were communicating the whole time, but this particular time … In the middle of all of that, one very disturbing part for me, we had the call that the aunty was having a hard time breathing. We were having a hard time breathing on our side. That was one very … one of the toughest moments in the storm, because we could definitely … we were living this horrible nightmare. Then you get the call that she’s not breathing. She’s probably passing on now, and the culture is to come to the aid. This is one aunty to everybody, this is the oldest person in the whole atoll actually, and nobody could move. They’re calling me, the aunties were calling me that they need help. All the windows had broken and everything’s wet, the water from the storm. Nobody responded. Nobody responded, because everybody could hear, but nobody responded. What do you say? What’s the right thing to say? I struggled with that, because I had to respond, and we had to make the call for everybody to stay put. It was hard because I was trying to figure out how to say this to comfort the people on the other side but also tell them not to move. You want to keep the spirit up that somebody is coming soon, but you don’t want to give the impression for everyone to run over and somebody get killed. That was the toughest part the entire time. I just said “We can only pray, we’re praying with you. We’re all in the same situation, nobody is dry right now. As soon as we can move, we will.” Those are the best things I could think of at that time to say without giving the wrong information because everybody’s listening. I was very mindful of, I want to comfort you guys I want to keep you spirits up, but I also want to give the message not to move. That was probably the toughest part of all of this, to make that call. The next day I got positive feedback about that, like “Oh, thanks for saying that because we were going to do this, if you said we should all run there, we will.” People were just waiting for somebody to say something, nobody was really thinking. Now looking back, that was probably the toughest.

After that, nothing could have beat that because the storm slowed down. I don’t think it really slowed down until the next morning, but it felt a little relief, when it was going less than 100 miles, we thought it was fine having gone through the 160.

Everybody kind of dozed out about 2:00. I want to say about 5:30 or … before 6 because by 6, we tried to open the door to our shelter. Before that, we had a good talk among ourselves. All I managed to think of at that time was to say, “Please expect the worst before we open the doors. There’s probably people hurt, maybe people dead … Maybe there’s people that are cut in half.” I gave them a very bad scenario before we opened the doors. Just to keep some expectations so we don’t freak out when we open. We let the kids stay inside and we made an opening around the door.

Boy, if I hadn’t been through a war, this was it. It felt like a war zone, or what I can imagine a war zone would look like. My first stop was going down to the chief, Rafael, and calling Mario. We met there and just kind of, okay, everybody’s okay. The first thing we did after that was visiting the shelters that didn’t have a radio. At this point, we knew everybody in the shelters with no radios were fine. We knew nobody was hurt badly.

We had everybody accounted for and we decided we were going to focus all the attention on the funeral, to focus everyone’s attention on something. It became that, and then the mass service part of that funeral. This was Easter week, so …

We didn’t really talk about cleanup, other than the water to try to be … whatever water is still there to conserve. We collected food with shorter shelf life. Those were the only things that seemed organized or directed.

The first flight with relief came on Thursday morning. On Thursday morning, the decision was made to open the access to the beach and the plane, anticipating that if somebody is coming that they would need access, if help was coming we’re going to need access. That was the big thing to do on Thursday, and collecting food so that it doesn’t go bad. Friday we gave out the first relief, Friday or Saturday. Between Friday and Saturday, I’m not sure. All the taro was collected that morning and distributed that evening from Falalop.

We communicated with the other islands by 10:00 the next day. 9:00 it was still stormy, by noon we had communicated with all islands within the atoll. We didn’t communicate out until maybe the afternoon.

Other than the concrete houses, there were no roofs on all of the houses. All of the houses that didn’t have … that was tin, was gone. All of it. Forget the traditional ones, those were gone completely. I don’t know, it’s the worst thing you can imagine. I had no … I couldn’t think of some other incident to compare it to besides being like a war zone. It feels like walking in CNN, I’ll tell you that.

There was a sense of … There was some sense of, it didn’t really kill the spirit. I didn’t see anybody crying, it was more … Maybe the adrenaline rush was still going. Some were laughing out of nervousness. Some were just … You know, what do you do? People didn’t really … I don’t think it really kicked in until much later.

One thing I observed was that, usually when people go to the funeral they morn. I don’t think much of that happened in a normal sense. I was actually thinking that it would intensify, there would be more wailing and morning, because we just went through that. People were shocked, I think. We sat there stone-faced, waiting for people to give direction. Shock, total shock.

On the positive side, this recaptured the future of these whole islands. There’s a real realization of the vulnerability that we have, that I think will just add to the work and attention that people are doing, at least on the local level. This is an opportunity to rebuild back better and stronger.

Comments by sara cannon