Bilingualism and self-translation may be used to question or redefine one’s cultural identity and to dislocate and decentralize contextual dominant idioms. I stress the word contextual because idioms become dominant depending on the context in which they are actively practiced and pursued. The writer Antonio D’Alfonso’s Italian, for instance, is perceived as a minority language in the Canadian context, but it is definitely lived as a dominant idiom by migrant or foreign writers trying to find their way into the Italian literary system. In this regard, D’Alfonso, like the writer Tim Parks (who lives in Italy and mainly writes in English), is considered an outsider whose Italian is not sufficiently refined or literary enough in the eyes of the local/national intelligentsia. As the Italian writer Francesca Marciano comments, “Italians haven’t yet got rid of a certain elitist and pretentious view of literary style. They still have to undergo the stylistic revolution that the English went through with its Hemingways, Carvers and Faulkners” (Dagnino and Marciano, 2017).

Bilingualism and self-translation may be used to question or redefine one’s cultural identity and to dislocate and decentralize contextual dominant idioms. I stress the word contextual because idioms become dominant depending on the context in which they are actively practiced and pursued. The writer Antonio D’Alfonso’s Italian, for instance, is perceived as a minority language in the Canadian context, but it is definitely lived as a dominant idiom by migrant or foreign writers trying to find their way into the Italian literary system. In this regard, D’Alfonso, like the writer Tim Parks (who lives in Italy and mainly writes in English), is considered an outsider whose Italian is not sufficiently refined or literary enough in the eyes of the local/national intelligentsia. As the Italian writer Francesca Marciano comments, “Italians haven’t yet got rid of a certain elitist and pretentious view of literary style. They still have to undergo the stylistic revolution that the English went through with its Hemingways, Carvers and Faulkners” (Dagnino and Marciano, 2017).

By his own admission, D’Alfonso started off self-translating with the aim of expanding his readership and acquiring literary recognition outside the stifling cultural and linguistic borders of French Quebec:

Most of my essays written in French have never been published in French. All my essays I had to translate and publish in English. My anti-nationalism […] is clearly not appreciated by my French-language publishers […].

Dagnino and D’Alfonso, 2017

D’Alfonso thus started off as a Widener, willing to expose his work to a wider, English-reading audience. In the process, though, he understood that he could also use self-translation as a tool to call into question the centrality of two of the most influential languages (and their related literary cultures) on the global scene—namely, English and French. Consequently, he assumed the role of a Decentralizer:

Translations are required to demonstratively promote the nation’s agenda. This is why in many cases, it is the translator who is applauded and not the author of the original text. When critics speak of one translation being better than another, it is often because the translator has elaborated something that is uniquely national. We experience this reservation whenever we have to negotiate the French translation of an English-language writer: does the publisher hire a translator from Canada or one from France? This proves that language is irrefutably centralized. Whenever translation is decentralized, it is ignored.

Dagnino and D’Alfonso, 2017

That is why D’Alfonso’s self-translations may also be read—quoting him—as “subversive acts, perhaps the most subversive acts in the world today” (ibid.). We should not forget that, indeed, we are dealing with a global literary scene in which, if we just look at the United States, the biggest publishing market on earth, only an infinitesimal part of published books are translations: “The sad statistics indicate that in the United States and the United Kingdom, for example, only two to three percent of books published each year are literary translations” (Grossman, 2011, n.p.).[17] A closer look reveals an even worse state of affairs, as the two to three percent figure is considerably bolstered by technical manuals and other non-fiction texts. For literary fiction and poetry, the figure is actually closer to 0.7%.[18]

D’Alfonso’s task of acting as a language dislocator through self-translation is tremendously ambitious and perhaps defiantly hopeless, as he admits:

(Self-)Translation means leaving your windows open for the passers-by… [But] who are we to want to pretend to have something new to offer to cultures that have shut tight the gates of national imagination? […] If one considers that translations are rarely read and never reviewed, a translation is a waste of time for any writer who is content on reading himself and his buddies. Why read an author who introduces a worldview and works in a style totally foreign to yours? To do so would demonstrate an openness of spirit that is, in fact, atypical.

Dagnino and D’Alfonso, 2017

Full article

You can read the full article by Arianna Dagnino, published in the journal TTR, here: https://www.ariannadagnino.com/post/bilingual-writers-self-translation-and-the-stylistic-revolution

Arianna Dagnino, “Breaking the Linguistic Minority Complex through Creative Writing and Self-Translation.” TTR-Traduction, Terminologie, Rédaction, Volume 32, Issue 2, 2e semestre 2019/2020, pp. 107-129.

Biographical note

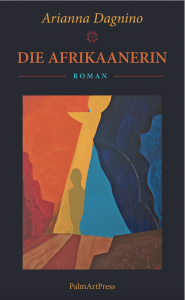

Arianna Dagnino is a writer, researcher and literary translator with extensive experience as an international reporter. She holds a PhD in Comparative Literature and Sociology from the University of South Australia and currently teaches at the University of British Columbia. The recipient of a SSHRC postdoctoral fellowship (2017-2019) at the University of Ottawa (School of Translation and Interpretation), her publications include Transcultural Writers and Novels in the Age of Global Mobility (Purdue University Press, 2015), The Afrikaner (Guernica, 2019), a transcultural novel set in South Africa which she self-translated from Italian into English, and several books on the impact of information technology and global mobility: I nuovi nomadi (Castelvecchi, 1996), Uoma (Mursia, 2000), and Jesus Christ Cyberstar (Ipoc, 2008). www.ariannadagnino.com

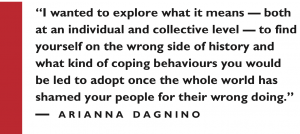

Alan Twigg’s review of my novel The Afrikaner in the spring issue of “BC Booklook” goes to the core of the predicament faced by the protagonist of the story, Zoe du Plessis, a young female scientist (33) who grew up in South Africa in a deeply entrenched white family: “Zoe is little concerned with money, status or personal appearance. Instead she seeks belonging.”

Alan Twigg’s review of my novel The Afrikaner in the spring issue of “BC Booklook” goes to the core of the predicament faced by the protagonist of the story, Zoe du Plessis, a young female scientist (33) who grew up in South Africa in a deeply entrenched white family: “Zoe is little concerned with money, status or personal appearance. Instead she seeks belonging.”

of her Afrikaner heritage. Set between South Africa and the Kalahari Desert in Namibia, the story of palaeontologist Zoe du Plessis, the Afrikaner of the book title, has the ability to cross borders and resonate with the hearts and souls of readers far away from the hot plains of southern Africa. Because all people have a history and all nations have bloodlines. They all get shaken up and suffer trauma. But they all learn to cope with the past, learn from it and find a resolution. This is the underlying message running through The Afrikaner, which after its English publication will soon be available in German, Arabic, Italian and Afrikaans. Covid-19 permitting, the German translation will be launched at the 2020 edition of the Frankfurt Book Fair in October.

of her Afrikaner heritage. Set between South Africa and the Kalahari Desert in Namibia, the story of palaeontologist Zoe du Plessis, the Afrikaner of the book title, has the ability to cross borders and resonate with the hearts and souls of readers far away from the hot plains of southern Africa. Because all people have a history and all nations have bloodlines. They all get shaken up and suffer trauma. But they all learn to cope with the past, learn from it and find a resolution. This is the underlying message running through The Afrikaner, which after its English publication will soon be available in German, Arabic, Italian and Afrikaans. Covid-19 permitting, the German translation will be launched at the 2020 edition of the Frankfurt Book Fair in October.