A growing number of bilingual writers are now self-translating their work, from or into English. Why is this happening? What does the process of self-translation imply in terms of cultural negotiation? And what happens to the cultural dimension of the self-translated text in this translative movement?

A growing number of bilingual writers are now self-translating their work, from or into English. Why is this happening? What does the process of self-translation imply in terms of cultural negotiation? And what happens to the cultural dimension of the self-translated text in this translative movement?

Self-translation has been efined as “the act of translating one’s own writings into another language and the result of such an undertaking” (Grutman 2001, 17).

The reasons why nowadays writers decide to self-translate are manifold and closely linked to growing migratory flows, diasporic movements and transnational relocations, which have created new generations of bilingual writers, especially in settler countries such as Australia, Canada, New Zealand, South Africa and the United States, or in former colonial powers such as France, Spain and the UK.

Drawing upon existing literature and a series of one-on-one interviews with six self- translators, I have identified and compiled a list of reasons for which writers decide to self-translate based on their self-perceived level of bilingual proficiency and socio-cultural status (that is, whether they are emerging writers or already established writers, whether they are mainly active in a minority language or in a majority one). I have also produced a Table that summarizes my findings and that I provide herewith (see Table 1).

Whatever the reasons for self-translating may be, in most cases English is always part of the equation (whether writers decide to self-translate from or into it). Undoubtedly, as Philipson (2009, p. 10) remarks, nowadays English plays a dominant role not only as “lingua economica” but also as “lingua emotiva,” “lingua bellica,” “lingua academica,” and, most importantly, “lingua cultura.” As publishing consultant Jane Friedman notes,

When it comes to global sales, books in English are at an advantage. English is spoken as a first language by around 375 million people and as a second language by an additional 375 million people. Around 750 million people speak English as a foreign language (where English is not spoken as a first or second language). One out of four of the world’s population speaks English to some level of competence, and demand from the other three-quarters is increasing (n.p.).

Thus, for most writers the choice of English – especially when adopted in a translingual mode as the primary language of creative expression – is highly justified by its role as the dominant global idiom (De Swaan 2001; Philipson 2009).

Self-translation requires a huge effort in terms of cultural mediation and literary re-creation. As such, it is usually practiced by a small number of writers who are not only bilingually but also biculturally proficient. As they move into the role of translators of their own work, writers need to devise strategies of cultural reframing and intertextual transfer which imply a renegotiation of their cultural identity and creative sensibility. In so doing, more or less consciously, these writers use the process of self-translation to translate not only their texts but also their cultural selves into another linguistic and cultural milieu, contesting the idea of a single, self-contained identity and embracing instead the notion of a dialectic, pluricultural self.You can read t

The whole article “Translingual writing and bilingual self- translation as transcultural mediation” published in Traditions and Transitions (Sofia University), here.

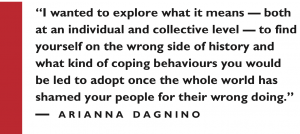

I myself have self-translated from Italian into English my transcultural novel The Afrikaner (Guernica, Toronto, 2019), inspired by the five years I spent in South Africa as an international reporter. www.ariannadagnino.com

Alan Twigg’s review of my novel

Alan Twigg’s review of my novel

of her Afrikaner heritage. Set between South Africa and the Kalahari Desert in Namibia, the story of palaeontologist Zoe du Plessis, the Afrikaner of the book title, has the ability to cross borders and resonate with the hearts and souls of readers far away from the hot plains of southern Africa. Because all people have a history and all nations have bloodlines. They all get shaken up and suffer trauma. But they all learn to cope with the past, learn from it and find a resolution. This is the underlying message running through The Afrikaner, which after its English publication will soon be available in German, Arabic, Italian and Afrikaans. Covid-19 permitting, the German translation will be launched at the 2020 edition of the Frankfurt Book Fair in October.

of her Afrikaner heritage. Set between South Africa and the Kalahari Desert in Namibia, the story of palaeontologist Zoe du Plessis, the Afrikaner of the book title, has the ability to cross borders and resonate with the hearts and souls of readers far away from the hot plains of southern Africa. Because all people have a history and all nations have bloodlines. They all get shaken up and suffer trauma. But they all learn to cope with the past, learn from it and find a resolution. This is the underlying message running through The Afrikaner, which after its English publication will soon be available in German, Arabic, Italian and Afrikaans. Covid-19 permitting, the German translation will be launched at the 2020 edition of the Frankfurt Book Fair in October.

I thank the South African writer

I thank the South African writer