CPR – or Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation – is a lifesaving technique most commonly employed in response to a heart attack. During CPR the patient manually has their heart pumped through compressions on the chest. CPR does what it can, but even at optimal rates, it only offers 25% of normal blood flow and the damage that occurs to important organs from prolonged lack of oxygen-rich blood during the wait for emergency medical response teams to get there can be fatal. This is why doctors developed ECPR, but is it really the saviour we’ve been looking for?

CPR demonstration from Season 5 Episode 14/15 of “The Office”. GIF courtesy of Giphy. Footage courtesy of NBC.

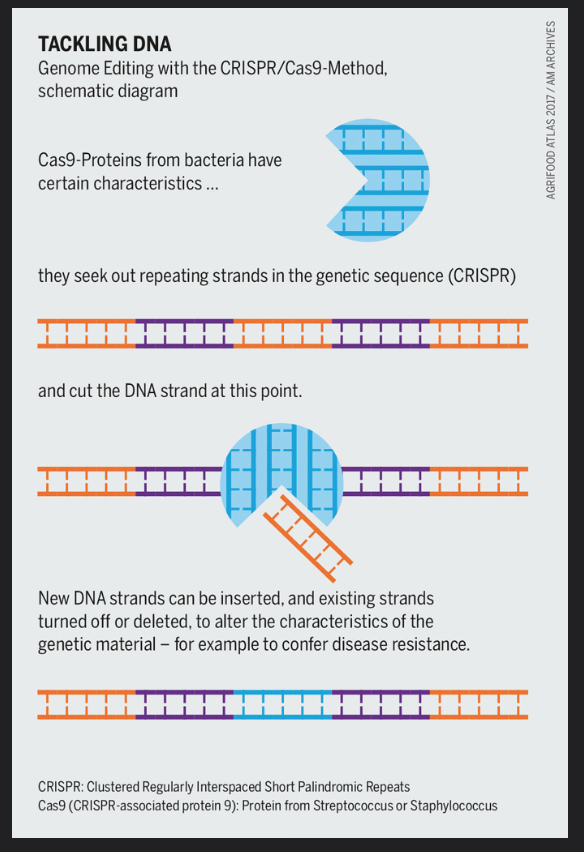

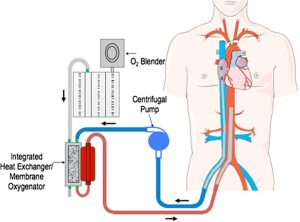

ECPR, which stands for Extracorporeal Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation, is a device which mechanically routes the blood outside of the body where it is infused with oxygen and then pumped back in. That makes the 25% flow rate CPR produces suddenly skyrockets to 100%. It’s already implemented in some hospitals to help support patients during heart surgery or children suffering from heart failure, so what’s stopping them from installing one in every public space? Well, a lot of reasons actually, the simplest being that ECPR is an advanced technology which requires extensive training to operate, something which cannot be provided to enough people in the public to ensure someone is always able to perform it.

Diagram Outlining how ECPR pumps blood. Image courtesy of Mehrdad Golian.

Nevertheless, countries around the world including Japan, the Czech Republic, and the Netherlands are beginning trials comparing ECPR with CPR to see if it is a viable option to increase the likelihood of surviving an out of hospital heart attack. However, questions are arising regarding the quality of life the patient may have afterward that is causing many health care professionals anxiety. Of the patients who are treated with ECPR, only about 40% survive and most are left with some degree of cognitive impairment from mild short-term memory loss to severe brain damage often causing death from future complications.

Medical Training Video on how to implement ECPR.

ECPR also presents a serious moral dilemma to those who have to implement it. To use ECPR, an invasive process needs to be performed that involves putting large tubes into the groin of the patient. A procedure of this type would generally need permission from the patient beforehand to be performed but that is not always an option during a heart attack. Furthermore, CPR has concrete guidelines outlining when to stop but if heart function is being fully supported by an outside source (such as ECPR) the lines of when to stop or “pull the plug” become blurred. Perhaps the most sobering drawback to ECPR is that the majority of patients who use it still die. When death occurs while using ECPR it is not a sudden death but instead slow organ failure, a risk patients often don’t find equal the reward.

The idea behind ECPR is a genius one and does have the potential to revolutionize the treatment of heart attacks but scientists know that some serious design flaws must first be overcome. If a cheaper, easier to use model could be developed that produces a higher success rate with milder risks, the public would not waste a moment implementing them everywhere they can.

-Tenanye Haglund