The UBC School of Nursing I-CAN Project was conferred the 2017 Quality Culture Trailblazer Runner-Up Award by the BC Patients’ Safety and Quality Council (BCPSQC).

Team Leaders- Dr. Maura MacPhee (Professor and Synthesis Projects Course Leader) and Ranjit Dhari (Lecturer and Community Nursing Course Leader).

Student Members- Maryam Koocheck, Rebecca Anthony, Zachary Daly, Laura Gallagher, Julie Wasson, Jessica McIntyre, Erin Kang, Ornella Marinic, Narissa Mawji.

Administrative coordinator- Khristine Carino (UBC SoN Flexible Learning Coordinator).

Some members of the UBC School of Nursing I-CAN Team. (Photo by Khristine Carino)

Summary

The I-CAN Team from UBC School of Nursing partnered with Union Gospel Mission (UGM) to address basic care needs of UGM clients, beginning with foot care. From March to May 2016, students completed an Institute for Healthcare Improvement certificate course on community engagement. Students, staff and clients identified care interventions to prevent disability, promote better quality of life, and facilitate appropriate utilization of inner-city resources. UGM now receives regular, nurse-driven foot soak clinics where students do foot care assessments and determine whether or not clients need primary care referrals. The students are piloting a primary care referral process to decrease reliance on emergency services. The outcome: Great relationships between UBC and UGM and essential on-site foot care and assessment. Ongoing evaluation based on the BC health quality matrix, will determine whether or not this student-driven project has improved health care quality for one of Vancouver’s most vulnerable populations.

THE TRAILBLAZER’s LANDSCAPE

What areas of your workplace’s culture was changed as a result of the project?

A directive from the provincial Ministry of Health is to shift care from acute care settings to the community. People have a better quality of life when they are cared for in their homes and communities, and community-based care is more affordable and sustainable. At UBC School of Nursing, our curriculum includes content on community health/population health and home care, but most students gravitate towards high technology and high acuity clinical placements and careers.

A directive from the provincial Ministry of Health is to shift care from acute care settings to the community. People have a better quality of life when they are cared for in their homes and communities, and community-based care is more affordable and sustainable. At UBC School of Nursing, our curriculum includes content on community health/population health and home care, but most students gravitate towards high technology and high acuity clinical placements and careers.

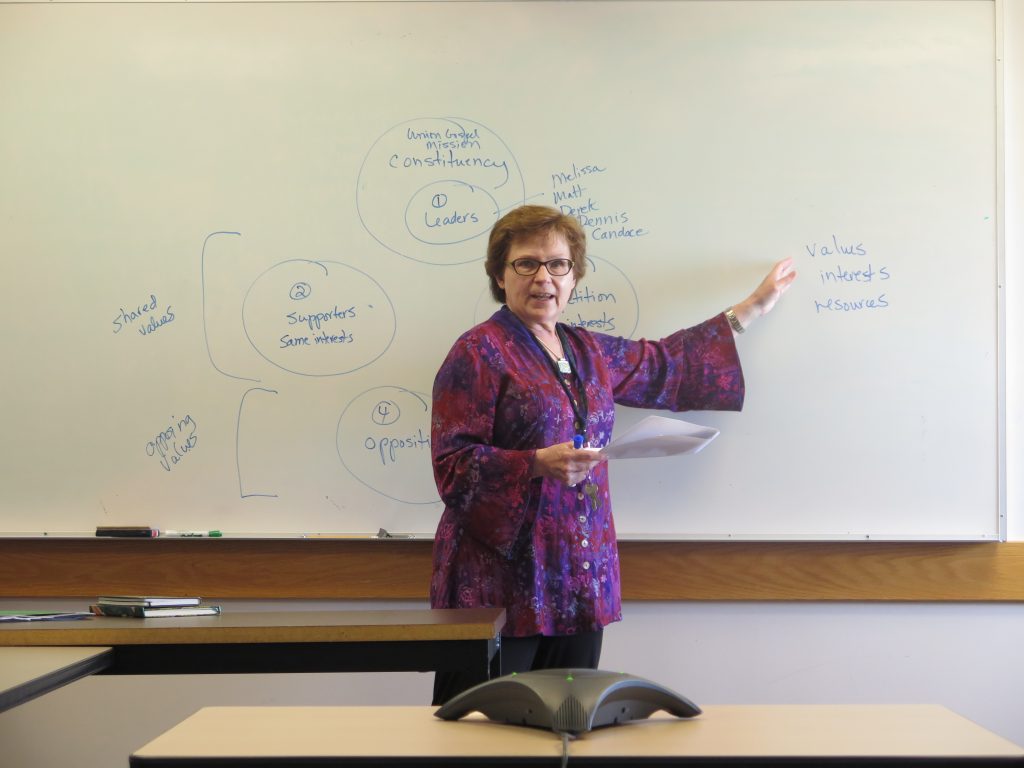

The goal of this UBC School of Nursing project was to change students’ thinking about working in the community, particularly with vulnerable populations. Two nursing faculty and ten students volunteered to pilot the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) I-CAN certificate program, an 8-week program to engage health disciplines students in the community. Our community health faculty made initial connections with a non-profit organization, the Union Gospel Mission (UGM) in inner-city Vancouver. Students were accountable for identifying their project stakeholders, creating a network of inner-city supports for their project, negotiating project deliverables with UGM staff and clients, and carrying through on their project commitments. Faculty, students and staff met regularly to debrief on project work, with students taking the lead on meeting agendas and follow-up actions and communications.

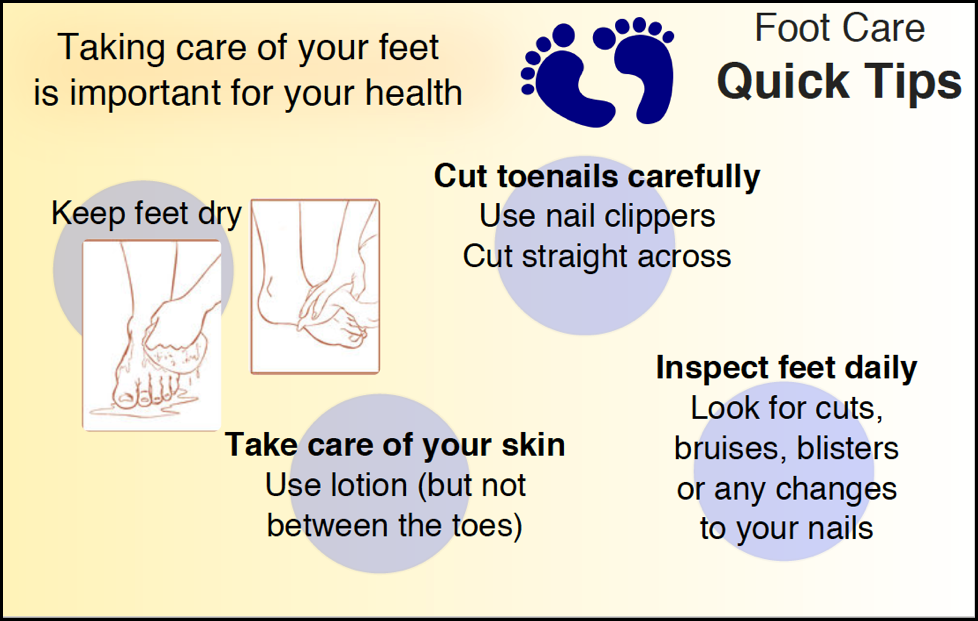

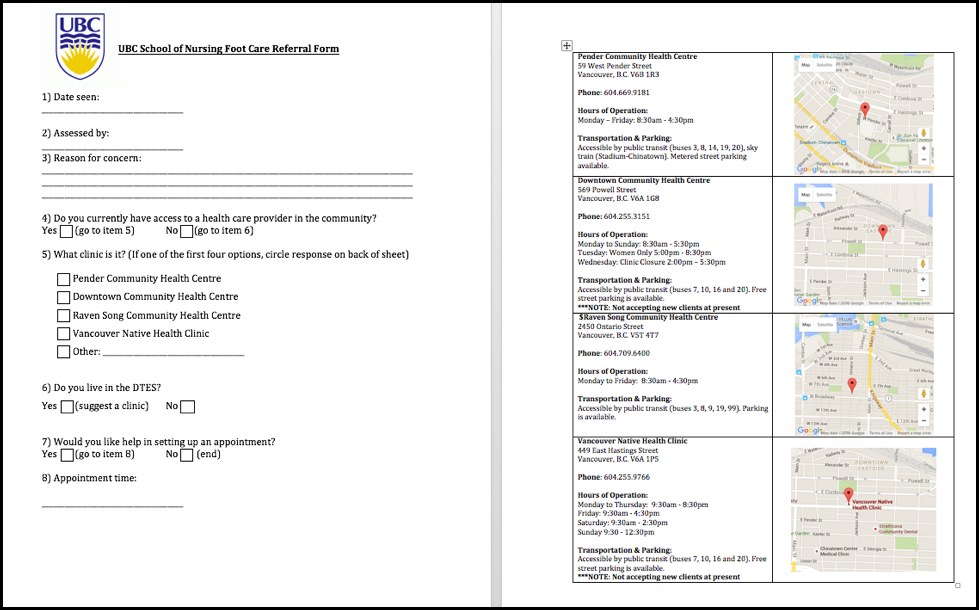

The students were impressed with their capacity to enact change within a short period of time. The I-CAN approach promotes a cycle of actions similar to the Plan-Do-Study-Act cycle. At the end of the 8-week project, students produced a “Foot Care Tips” card to share with clients during their foot soaks; a foot care assessment resource for students to use, covering aspects of foot care such as prevention of trench foot; and a primary care referral process, based on students’ discussions with primary care clinics in the inner-city, such as Pender Clinic and Raven Song. The experience was described by students as “empowering,” “energizing,” “a real eye-opener of what we can do to make a difference.”

The students began this project with trepidation and anxiety about working with clients coping with homelessness, mental health and addictions, and numerous physical conditions. By the end of the project, these students were converts: volunteering after the project to continue work with UGM and other inner-city programs, and seeking out other community health learning opportunities. As an example, due to the short duration of this 8-week program, students were unable to evaluate the impact of their project work on UGM clients’ quality of care.

In addition, they instituted a primary care referral process for UGM clients with foot care needs, but they were unable to assess the impact of this process with respect to clients’ use of inner-city primary care services. They have therefore, created a proposal to evaluate project outcomes during their fall term, recruiting peers from their class to carry on their project work. In addition, they have ‘spread’ their work by identifying other project opportunities with other non-profits, such as the Evelyn Saller program. Most recently, the students helped the Evelyn Saller program organize a “Connect Day” for inner-city residents. Students and faculty provided blood pressure screening, diabetes education and counseling, and foot soaks and assessments. One of the students acquired donations from restaurants and groceries to offer free, nutritional food for Connect Day attendees. Given the success of this one-day event, Evelyn Saller staff and students have been exploring other ways to continue their collaboration. As described by IHI, the students are building an intricate “snowflake” of connections in Vancouver’s inner-city that is growing—rapidly.

In addition to learning how to engage community partners and seek commitment, the students learned how to work as a team, sharing leadership for different components of the project, depending on each other’s talents and skills. A group of loosely connected students became a cohesive, collaborative team. UGM staff repeatedly commented on the students’ capacity to work well together towards their common goal: improved health care for a very needy, challenging population.

As faculty, we can attest to the success of this project: students developed a sense of purpose and caring for a population they had initially avoided. Through the I-CAN project, this student team learned first-hand about the social determinants of health—how circumstances can impede our capacity to stay healthy, to get better, to live with disability and cope. In a small space of time and through some basic care interventions, students learned how to make a positive difference.

IMPACT

How did the project change the workplace’s culture so that team members thrive and patients receive the best care possible?

UBC School of Nursing has an accelerated baccalaureate program (BSN) this is one of the shortest BSN programs in Canada. Approximately 90% of students have a previous degree with a wide array of life experiences. In 18 months, as faculty, we must shape students’ professional identities—to become nurses with a strong code of ethics and professional standards. We are constantly striving to find experiential learning opportunities for students where they can experience the spectrum of care delivery and find their niche within the healthcare system. For most of our students, they have traditional conceptions of what nurses do and where nurses deliver care. Not surprisingly, the social media, TV and movies emphasize life and death in highly technical, acute care settings. When we ask students what they want to do at the beginning of our program, we hear: “I want to work in emergency services or trauma.” “I want to take care of very sick children and babies.” “I want to work in the ICU.” We rarely hear students say: “I want to go out in the community and take care of people who are fragile, people who have lots of mental health and physical issues.” “I want to work in an environment with limited resources, where my supports are limited.”

Through this project, we started out with one kind of student and we ended up with a totally different kind of student. We began with students who had a naïve appreciation of life in the inner-city, and by the end of the project, we had activists and advocates for better care and living conditions for Vancouver’s inner-city vulnerable population. As faculty, we noticed dramatic differences in students’ attitudes and practices, but at UGM, staff noticed it too. Here are some of their comments: “It was a great experience! I really enjoyed it. I was surprised at how much I liked it. It was a great way to connect with the community.” “It’s a great way to be in an intimate setting, break down barriers and assumptions and have a meaningful connection.” “My only concern was about feet because I’m not a big fan of being near feet, but it wasn’t as bad as I thought it would be because I knew that this is something the clients needed.” “It was also nice to talk to the clients during their foot soak and learning about some of their history and how they were doing at the moment. They really seemed to appreciate us coming in and talking to them.”” I thought the experience was great, I really enjoyed having a thorough tour of the facility, knowing that the homeless population is being treated humanely.”

The students are regularly asked to journal about their client experiences. The most poignant student reflections have resulted from their UGM client encounters. Here are some of their comments: “I was amazed at the array of services offered, the thought with which the care was structured and given, and the compassion that seemed to be exemplified.”” I was struck with the certainty that this was how many of the people lived their lives – probably most unwillingly – in a constant state of near-chaos, very little under their control. They struck me as people living in the oldest human ways, where talk is all the entertainment there is, and where it forms the raw material of safety in an often menacing world.“ “The experience of doing the foot soak at the Union Gospel Mission was intense and enjoyable alike – even inspirational. The nearness of this edge between survival and non-survival was very real in the room, and seemed to make each person into a full world unto themselves, rich with capacity. Even what was concealed was often spoken loudly in their guardedness, while they affected none of the insouciance of more well-off people, myself included, whose worlds seem smaller and paler by comparison, carefully folded into precise acts of private meaning and public competence. I felt quite inadequate to the situation, but also deeply privileged to have been part of it.”

INSPIRATION

At the very end of our program, before students do their final clinical preceptorships, they are required to do an 18-week capstone project. They can choose specific sectors (e.g., acute care, community, mental health) and specific topics (e.g., breastfeeding, dental health, immunizations). As a result of the success of the I-CAN project and its student team, the student body made a decision during a town hall discussion with faculty, that this year’s capstone projects should be community based. In fact, students have put forward project ideas based on the work of their I-CAN peers. As one example, a group of students has submitted a proposal to create a “pop-up” veterinary clinic for inner-city residents with pets. A student got the idea from social media and sought faculty assistance to crafting a proposal and discussing it with the director of the Evelyn Saller program. The student also contacted the founders of a pop-up veterinary clinic in inner-city Toronto and Toronto veterinarians who provide free services have connected the student with veterinarians in Vancouver. The student is now organizing a group of other students to help her recruit veterinarians and set up the clinic day. Students have also suggested ways to use time with clients at the clinic to add blood pressure screens and other care services that clients have requested.

At the very end of our program, before students do their final clinical preceptorships, they are required to do an 18-week capstone project. They can choose specific sectors (e.g., acute care, community, mental health) and specific topics (e.g., breastfeeding, dental health, immunizations). As a result of the success of the I-CAN project and its student team, the student body made a decision during a town hall discussion with faculty, that this year’s capstone projects should be community based. In fact, students have put forward project ideas based on the work of their I-CAN peers. As one example, a group of students has submitted a proposal to create a “pop-up” veterinary clinic for inner-city residents with pets. A student got the idea from social media and sought faculty assistance to crafting a proposal and discussing it with the director of the Evelyn Saller program. The student also contacted the founders of a pop-up veterinary clinic in inner-city Toronto and Toronto veterinarians who provide free services have connected the student with veterinarians in Vancouver. The student is now organizing a group of other students to help her recruit veterinarians and set up the clinic day. Students have also suggested ways to use time with clients at the clinic to add blood pressure screens and other care services that clients have requested.

Another group of students have connected with a transitional housing program in the inner-city: to do a capstone project that addresses the knowledge, attitudes and practices of contraceptive use. And another group of students wants to investigate inner-city healthcare workers’ understanding of trauma-informed practice.

In the past, faculty have had to ‘coax’ students to submit their project ideas by end of August. Since the student-faculty town hall decision to focus on community-based projects, the faculty coordinator has already received a full quota of project ideas from the student body: 90% of these projects are related to the original work of our 10 students in the I-CAN team. As faculty, we are deeply impressed with the impact of our student I-CAN team.

Finally, IHI Open School, the branch of IHI related to student participation in IHI online learning experiences, took note of our student’s I-CAN team. Out of 50 international community-based projects, our student team was asked to present their work via Webinar to a global IHI audience, and the students’ project report and deliverables are featured on the IHI Open School site. The recording of their presentation can be found at: http://bit.ly/29IQtWO

As faculty, we have never experienced this type of student-generated momentum. We are proud, inspired, and ready to repeat success with our incoming 2016 cohort.

INNOVATION

How has the project contributed to new thinking?

Innovation requires early adopters to take up new ideas and lead the way forward. The I-CAN student team consisted of 10 students who volunteered their time to take the course, connect with UGM, and make something happen. The UBC nursing program is very structured and lock-step: it is a tightly packed schedule of theory work, followed by clinical practicums. Although our students are intelligent and capable, they rarely have time to veer from our structured curriculum. In fact, there is no time for electives in our program.

Despite heavy workloads, 10 students volunteered for the I-CAN project. The majority of them indicated that they wanted a chance to “try something different,” “Take on a leadership role,” “Apply what I know in a different way,” and “See how far we can go with this type of project.” Some students were curious about community engagement. “I’ve taken community health, so how is it different?”

Although there were weekly online modules and learning exercises associated with the IHI I-CAN certificate program, students were expected to be innovative. Their biggest ‘ah-has’ were having conversations with community partners on their own; with minimal guidance from faculty. Due to our healthcare systems’ acute care focus, community services have been under-recognized and under-utilized as a learning resource for students. Through their collaborative project work with community partners, students soon recognized how they could contribute to care for members of the inner-city community, and they also recognized how they could learn a great deal through experiential learning opportunities. “This way of learning is so eye-opening, and it adds so much to what we learn in class and do in the hospital.” Students also learned that nursing is more than the roles and accountabilities of bedside nursing in the hospital. This project exposed them to the myriad roles that nurses can assume outside hospital walls.

Given the serious challenges facing healthcare in North America and globally, our next generation of healthcare leaders must be innovators: they must be able to think outside the box, propose potential solutions and take some calculated risks. The I-CAN students were initially frustrated by the lack of structure, rules and accountabilities. But they quickly grew comfortable with the lack of academic controls and their own self-direction. They produced some useful deliverables, such as foot care resources for students, UGM staff and clients; and a new primary care referral process. The most important resources generated through their efforts, however, were the solid relationships they established with community partners. On their own, through their “snowflake” network (IHI community engagement lesson), they initiated contact with a number of new partners for UBC School of Nursing, and this network is still growing because of student action.

We now have approximately ten new sites for students to visit. One site, for instance, is the Alexander Street Community program, an innovative collaboration between the government, a health authority and a non-profit. This program’s goal is to stabilize individuals who have been out on the street, and to help move them into permanent housing and employment. Within the facility where there is temporary housing, there is also a unique primary care model. The nurse director for this unit found out about the UBC students’ desire to engage with community partners, and students now have clinical placement options at the primary care clinic.

At the end of the 8-week IHI certificate program, students were asked to indicate what best practices from IHI resonated most with them. There were two best practices that most influenced our students.

One best practice is upstreamist thinking. Students loved the IHI analogy of going upstream to make the biggest positive difference. The second best practice is getting commitment. As one student said, “Maybes don’t count. You know where you stand with a No or Yes. We had more Yes’s than No’s with this project. Yeah!!”

RELATED

Read two UBC Nursing I-CAN students’ insights on their participation in the I-CAN Project:

1. Rebecca Anthony

2. Maryam Koocheck

Follow

Follow