By Philip Thomas Giese

| Name of the Artefact | Business window sign | Das kleine Volksblatt |

| Creator | Issued by local Belgian authorities | Vienna Austria: Albrecht Dürer Druckerei, Ges.m.b.H. |

| Date | 1941 | November 8, 1938 |

| Type | Paper, ink | Paper, ink |

| Image |  |  |

| URL | https://collections.vhec.org/Detail/objects/2229 | https://collections.vhec.org/Detail/objects/8146 |

Representations of the Social and Economic Exclusion of the Jewish People During the Holocaust

Overview

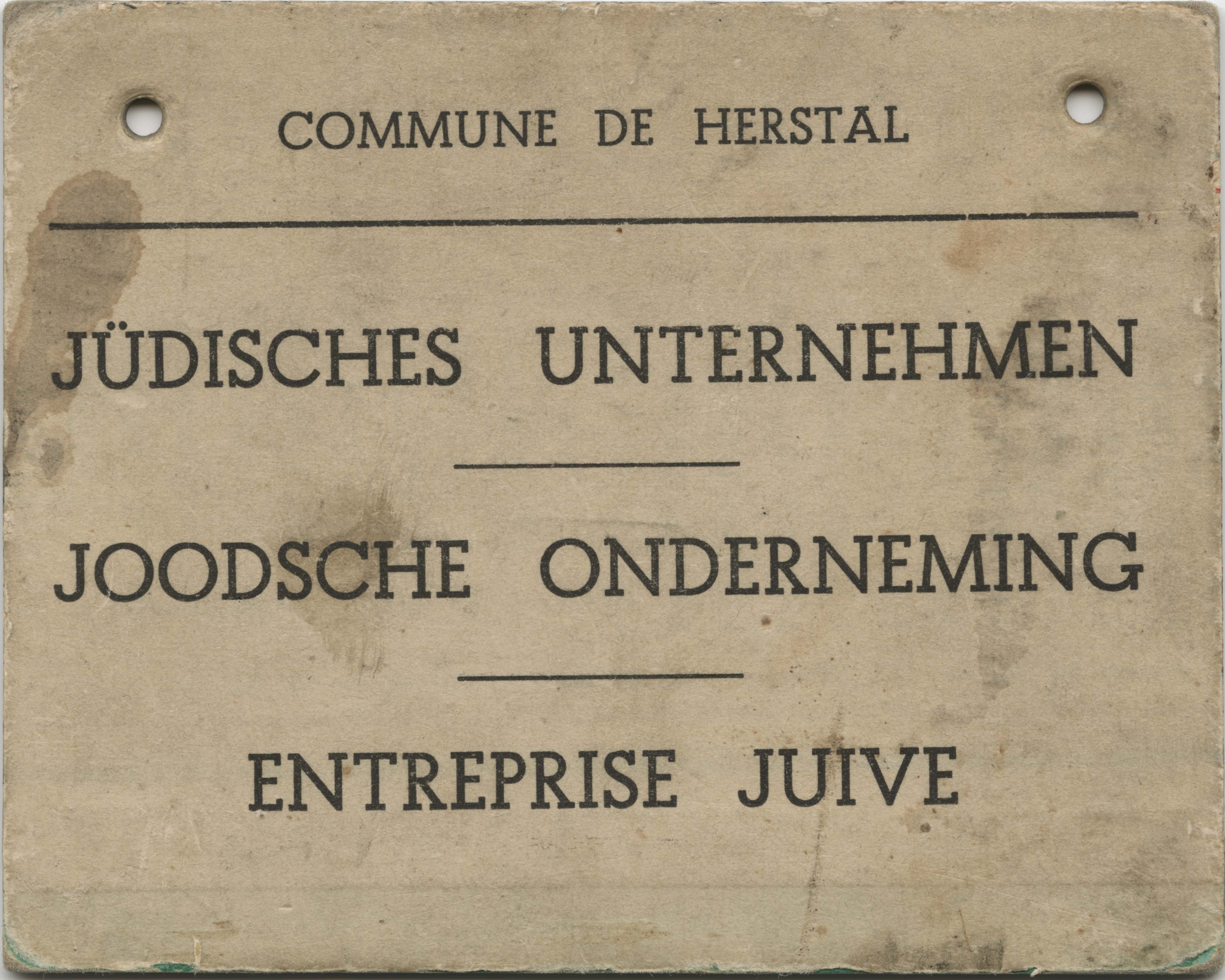

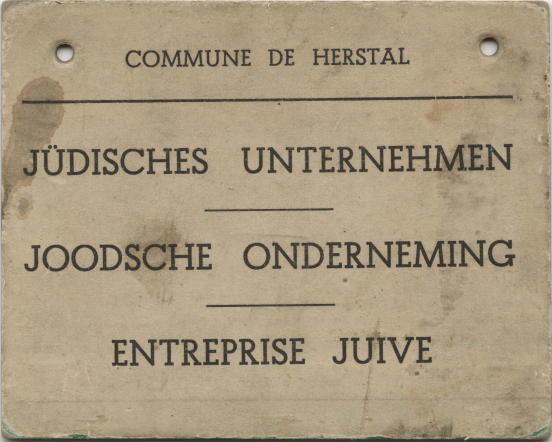

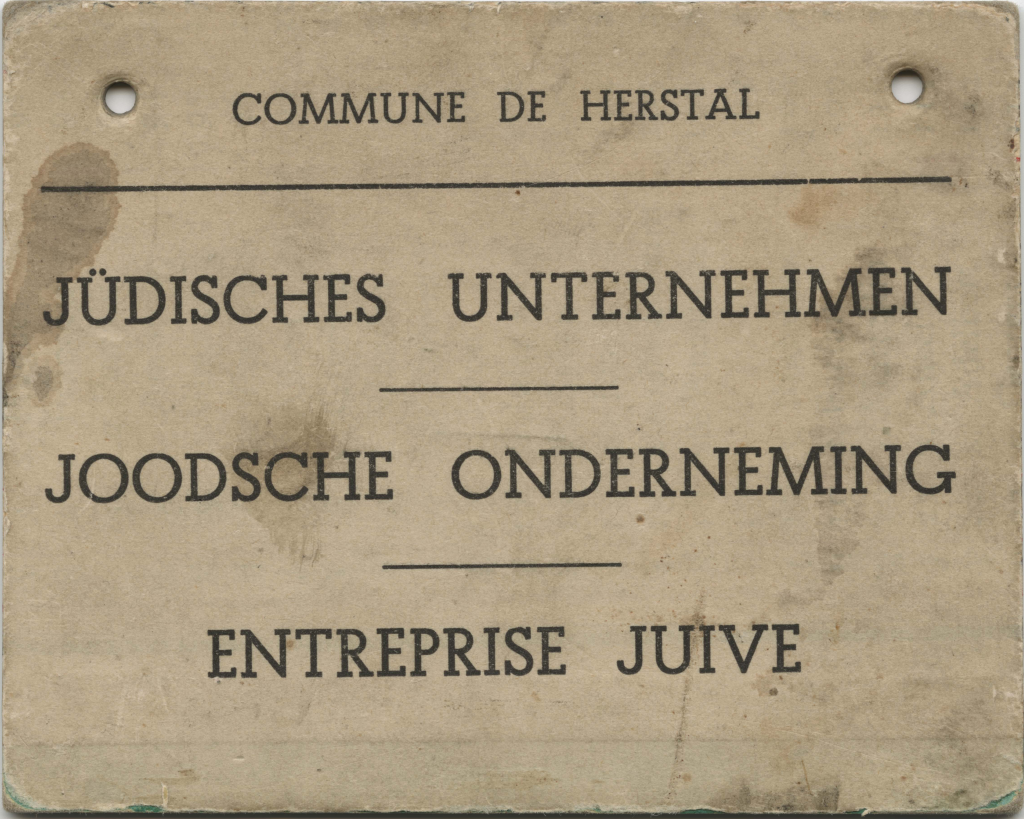

The first artefact is a business window sign made of paper and ink, stating the words “Jewish Business” in the three official languages of Belgium: German, Flemish, and French. These signs were used to label Jewish businesses, specifically in this case in Belgium, by placing them into the window, with the intention of warning non-Jewish citizens from shopping at Jewish businesses. This artefact was made and issued by the Belgian authorities in 1941.

The second artefact is an issue of the daily Viennese propaganda newspaper named Das kleine Volksblatt from November 8th, 1938, published by the Albrecht Dürer Druckerei Ges.m.b.H. in Vienna, Austria. The date November 8th, 1938 makes this specific issue historically significant, as it focuses on and utilizes the murder of the German diplomat Ernst von Rath by the Polish Jew Herschel Grynszpan in Paris, which triggered Kristallnacht (The Night of Broken Glass) that occurred on the night of November 9th to 10th.

Meaning

Despite their differing countries of origin and date of creation, both artefacts served to identify and mark Jewish businesses. While the business window sign (Artefact #1) was used to mark Jewish businesses, the issue of the newspaper Das kleine Volksblatt (Artefact #2) functioned as a call to action for the identification of Jewish businesses. However, it is important to distinguish between the role they played in the life of non-Jewish Germans (or Austrians or Belgians) and Jews, as the artefacts in particular were mediums for anti-Semitic propaganda and Nazi ideology.

The first artefact, for instance, was intended to warn non-Jewish individuals not to purchase any goods or services from this marked Jewish business. For this specific artefact, it is unknown in which Jewish business it was put up. As a result of such mediums of anti-Semitic propaganda, the Jewish people found themselves further isolated from German society and the German economy. The newspaper Das kleine Volksblatt was the Viennese counter-part to the Nürnberg-based Nazi propaganda newspaper known as Der Stürmer. Thus the second artefact primarily played an important role in the lives of Nazi party members and Nazi sympathizers in the Third Reich.

Symbolism

Both of these artefacts focus on the idea of marking and labeling Jewish businesses and properties. Therefore, these artefacts symbolize the utilization of the Germans, Austrians, and Belgians to identify Jewish businesses with the purpose of social and economic exclusion, as well as Aryanization. The radical social and economic isolation that occurred during this time in Germany, as well as in regions controlled by the Nazis, is portrayed in these artefacts, as they symbolize the early implementations of radical Nazi ideology.

Published on the day after the murder of Ernst von Rath yet preceding Kristallnacht, this specific issue of the newspaper Das kleine Volksblatt captures the utilization of a murder by a Polish Jew for anti-Semitic propaganda. Since these newspapers were a key medium for conveying racial Nazi ideology, this issue’s call to action, which reads “The Jewish businesses must be marked and labeled” in German, may have played a major role in triggering the riots on the night of November 10th. Nowadays known as The Night of Broken Glass, this event was a significant cornerstone in the progression of the Holocaust in Europe. In his survivor testimony, Primo Levi describes the Austrian Kristallnacht as particularly brutal and horrific. In The Black Hole of Auschwitz, Levi writes that the horrific events that occurred during Kristallnacht were the “first signs of Hitler’s megalomania” (57). The front page of this issue of Das kleine Volksblatt thus mirrors the Nazi sympathizers’ reaction to this murder and the utilization of it to trigger this horrific night of terror across the Third Reich.

As these artefacts symbolize the utilization of the people to implement racial ideologies through marking and boycotting Jewish businesses, leading to social and economic isolation, they play an important role in conveying and teaching the fact that bystanders knew what was going on at the time in the Third Reich. As Holocaust memorial sites have become essential cornerstones of representations of the Holocaust, such artefacts and survivor testimonies become more important in showing the ways in which German civilians were implicated in the progression of the Holocaust—in contrast to the myth of a Holocaust that is geographically distant from the German society.

Every stage of escalation during the Holocaust, from the early boycotts to the deportation of the Jewish people, occurred in German cities and towns. As Hilde Sherman states in her testimony: “I saw how the people [of the town] were watching. They did not go out on the street, they were watching from behind the windows. I saw how the curtains were moving. No one can claim they did not see. Of course they saw us. We were over one thousand people” (“From the Testimony of Hilde Sherman” 1).

Furthermore, one might argue that the two artefacts, which originated from Belgium and Austria, symbolize the extent to which the social and economic isolation of the Jewish people at this stage of the Holocaust was not only implemented in Germany by the National Socialists, but also the surrounding occupied Nations, and how these local authorities were cooperative. The first artefact, which was created in 1941, shows the implementation of the anti-Semitic, racial policies in the neighboring countries, such as Belgium, which were taken over by the Third Reich during the Second World War.

Aftermath

There has not been a significant change of meaning of the artefacts over time; however, it is important to note that such artefacts have become more important in understanding the Holocaust as they are among the few remaining physical representations of the Holocaust. Therefore, such artefacts increase in cultural value, as we are experiencing a more in-depth reappraisal and coming to terms with the Holocaust in society. These artefacts in particular are important in the reappraisal of the early stages of escalation during the Holocaust, as they help us understand the social and economic isolation of the Jews in Nazi Germany.

Such artefacts have also increased in cultural value over time as they originate from a time during the Holocaust prior to the Final Solution, which tends to be the main focus in modern-day teaching of the Holocaust. These artefacts, however, help us understand the social and economic isolation and exclusion that took place in Germany leading up to the Final Solution. Furthermore, as these artefacts originate from Belgium and Austria, respectively, they play a key role in teaching the Holocaust as an event which occurred in many nations beside Germany, and as previously mentioned, involved the cooperation of local authorities in Austria and Belgium.

As these artefacts symbolize the social and economic isolation of the Jewish people, and thus the early stages of escalation during the Holocaust, along with survivor testimonies they may help bring us closer to the answer, or even just may help us better understand, the underlying question that Germany society faces nowadays in the historic reappraisal of the Holocaust: How could this have happened?

Works Cited

Business window sign. 1941. Vancouver Holocaust Education Centre, https://collections.vhec.org/Detail/objects/2229

Das kleine Volksblatt. 1938. Vancouver Holocaust Education Centre, https://collections.vhec.org/Detail/objects/8146

“From the Testimony of Hilde Sherman about the Deportation to Riga and the Arrival to the Ghetto.” Yad Vashem Archives, The International School for Holocaust Studies, https://www.yadvashem.org/odot_pdf/Microsoft%20Word%20-%203287.pdf. Accessed 07 May 2020.

Levi, Primo. The Black Hole of Auschwitz, edited by Marco Belpoliti, Polity Press, 2005. ProQuest Ebook Central, https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/ubc/detail.action?docID=4860615.

Comments by Amanda Grey