By Charlotte Gibbs

| Name of the Artefact | Recipe Book | Comb |

| Creator | Rebecca Teitelbaum | Made by a concentration camp inmate |

| Date | 1944 or 1945 | 1944 |

| Type | Book | Object |

| Image |  |  |

| URL | https://collections.vhec.org/Detail/objects/7024 | https://collections.vhec.org/Detail/objects/2017 |

Objects of Femininity: Resistance in Concentration Camps

Overview

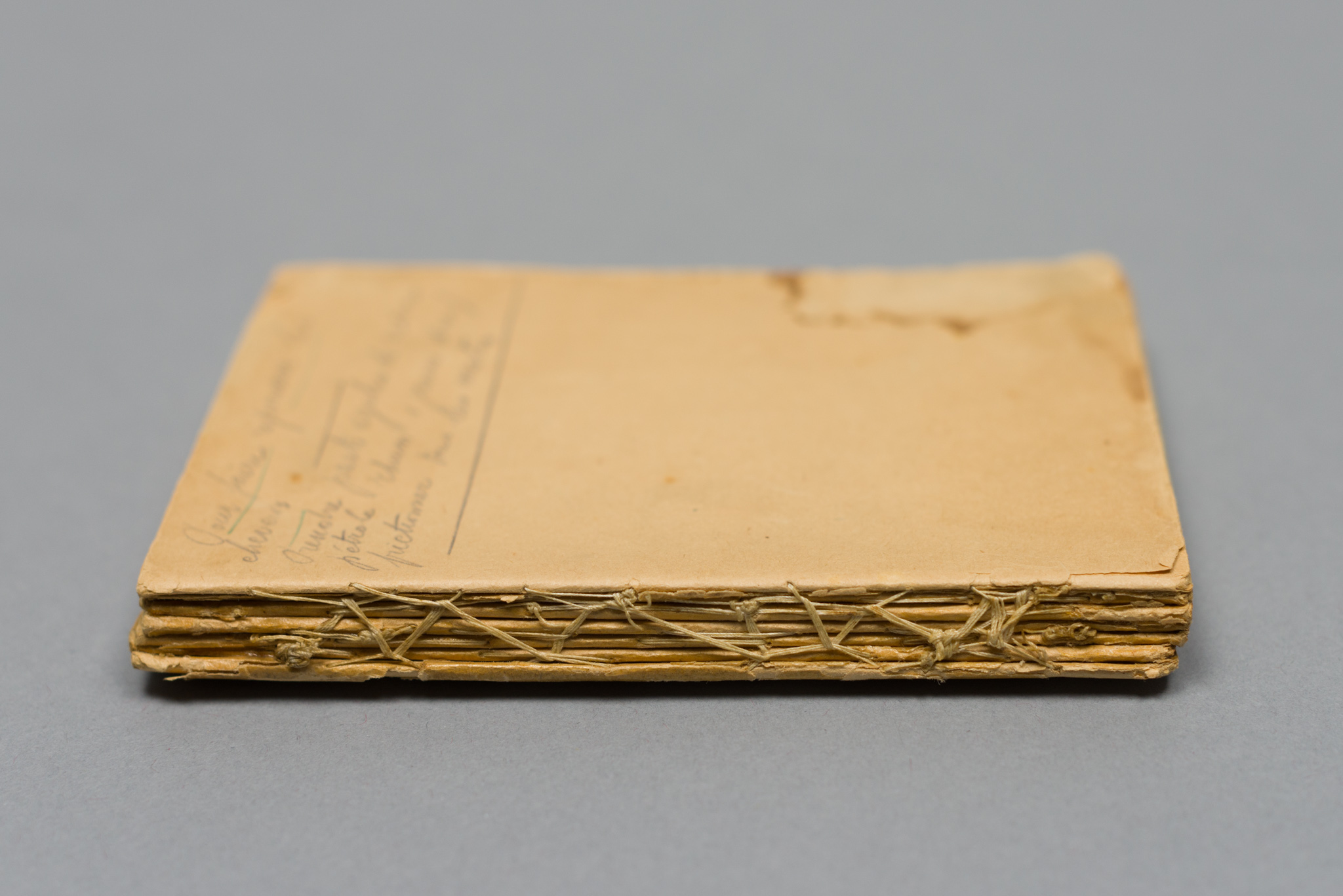

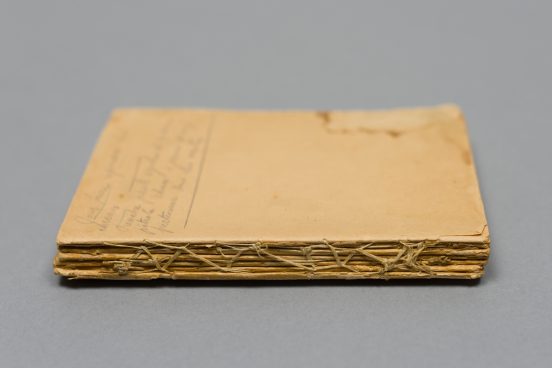

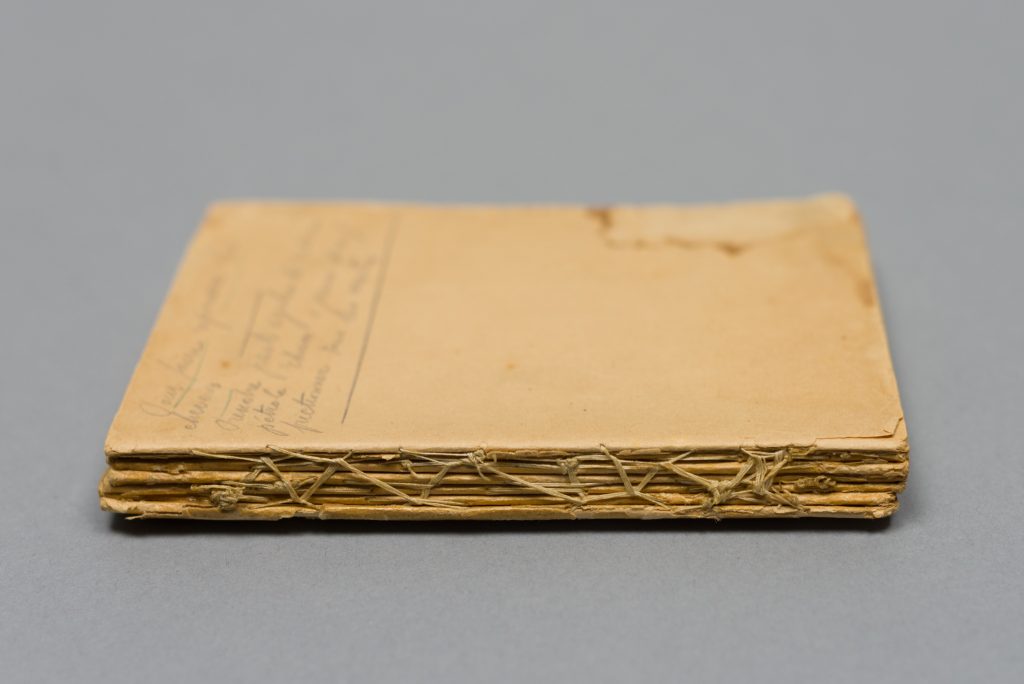

The first artefact is a recipe book with over 110 pages. It was put together by Rebecca Teitelbaum, a Jewish Belgian woman who was arrested in November 1943 and sent to Ravensbrück, an all-women’s concentration camp in Germany (Saidel 55). Creating this recipe collection was not easy. Teitelbaum had to steal the paper from her work placement in an office and traded food to get the needle and thread necessary to bind the book together (55). The book’s paper was conserved by placing two recipes on each page. The artefact was returned to Teitelbaum after liberation by a man who managed to track her down, as her name was attached to a collection of letters which were found with the recipe book (56). In December 1997, the book was found in an attic by Teitelbaum’s nephew, Alex, whom Teitelbaum and her husband adopted after the war after Alex’s parents were murdered in Auschwitz (56). One of the most famous recipes in the book is “gateau à l’orange” (orange cake). The Vancouver Holocaust Education Centre (VHEC) even serves it in their cafe.

The second artefact is a comb made for Sarah Rozenberg-Warm, about whom we know less than Teitelbaum. The comb was made in 1944 by a fellow prisoner at the HASAG slave labour camp in Skarzysko-Kamienna, Poland (Comb). The person who made it used stolen materials from the work site and is remembered by the initials “JN” (Comb). It would not have cost anything, as the materials were presumably stolen, but this act itself came with great risks.

Meaning

Teitelbaum and Rozenberg-Warm risked punishment for their actions. In Ravensbrück, Teitelbaum risked severe punishment, and even death, if she was discovered to be in possession of the recipe book (Saidel 14-15). At first, Ravensbrück was not intended for Jewish prisoners, as the central Reich had been proclaimed Judenfrei (Jew Free) (13).However, as the war progressed, it became an extermination site (20). Ravensbrück had a gas chamber that was in operation in early 1945, which the Nazis used to murder thousands of women (18). HASAG, where Rozenberg-Warm had been imprisoned, was a huge centre of production for the Nazi war effort, particularly for ammunitions (Karay 2). In 1944, 1200 women were transported to HASAG-Leipzig, where they became slave labourers for the Nazi war effort (2).

Both of these items—the recipe book and the comb—had extraordinary roles in the women’s lives who created and/or owned them while they were imprisoned in Nazi slave labour, concentration, and death camps. Inadvertently, both the comb and the recipe book aided in the morale and subsequent survival of Teitelbaum and Rozenberg-Warm, despite morale not being the primary purpose of their creation. Thus, one of the most significant things about the recipe book is the role it played in Teitelbaum’s survival. The recipes were collected from other prisoners in a process described as “cooking by imagination” (Saidel 54). This is described by Ravensbrück scholar Rochelle Seidel as a process where “women cooked with words—to bring back memories of home, assuage their constant hunger, and provide their campmates with food for thought in the true sense of the expression” (54). So, while the recipe book was created for prosperity, it raised the spirits of the women who shared recipes during their imprisonment in Ravensbrück. Similarly, the comb made for Rozenberg-Warm was shared by one prisoner (“JN”) with another, and this act of sharing would have added to its sentimental value. Like Teitelbaum and the women who shared recipes, “JN” would have had to risk punishment in order to make the comb.

Symbolism

Creating and being in possession of these two objects was in direct opposition to the Nazi agenda of dehumanizing the people in their concentration, death, and slave labour camps. Primo Levi argues that

the master’s purpose [was] to turn the slave into an abject person, who is known and who feels himself to be abject, a person who has not only lost his liberty but has forgotten it, no longer feels the need for it, barely even the desire. Generally he succeeds, and the material oppression of the individual is followed by a more painful victory, the victory of total oppression, in flesh and spirit, the demolition of man as man. (17)

Owning the recipe book and the comb are ways in which women committed acts of resistance against the Nazi agenda of completely destroying the mind, body, and soul of those they imprisoned. Levi speaks about resistance in the camps, and the importance of these acts of resistance for survival against the Nazi mission of the demolition of man:

Resistance in the concentration camps, like the resistance which developed in the Polish ghettos, should be numbered amongst the greatest victories of the spirit over the flesh, alongside the most heroic deeds of human history, the most desperate, fought with no covering fire and with no hope of victory to sustain the fighters and renew their strength. (17)

Levi goes on to speak about one of the most famous acts of resistance in a concentration camp, the uprising of the Sonderkommando at Auschwitz-Birkenau. However, these two artefacts are acts of resistance in these women’s daily lives. Käthe Anders, a young girl who was interned at Uckermark, a subcamp at Ravensbrück designed specifically for youth who were deemed “uneducable,” describes the acts of daily resistance that they took part in, such as “sticking together, never hurting one another, betraying no one, ‘organizing’ something together, sharing bread—that is all resistance. Resistance or solidarity.”[1] Resistance was not only seen in armed insurgencies that took out SS officers or an entire crematorium. Writing the recipe book or being in possession of a comb were also acts of resistance.

Moreover, both the comb and the recipe book are objects of traditional femininity, something that was denied to the women in the camps and would therefore have had a high value. Upon their entry into concentration or labour camps, external markers of femininity (such as long hair and feminine clothing) were stripped from the women. Holocaust survivor Lucille Eichengreen describes her traumatic initiation into Auschwitz, which included having her head shaved by an SS woman:

She laughed, enjoying every minute of our degradation. Pure hatred mixed with fear and pain swirled in my brain until I silently screamed and swore revenge. As if reading my thoughts, the SS woman slapped my face hard with the back of her hand. My head reeled back, but the Kapo kept on clipping. As she shaved my armpits and all other body hair, I concentrated on my hatred: hatred for her, hatred for the Germans who had reduced me to this sweating, naked creature, without hair, without dignity. I was no longer a human being to them, just an expendable Jew. (93-94)

Being able to own an object of femininity in a place where this was stripped from them in an extremely traumatic manner would have meant a lot to the women in the camp. As both of these artefacts are objects of femininity, being in possession of these objects in the camps is a distinctly female form of resistance.

In addition to being objects of femininity, these artefacts, and especially the recipe book, demonstrate just how important collaboration was among the women. The recipe book included 110 pages of recipes, something that Teitelbaum would not have been able to put together without help from the other women she lived with in Ravensbrück. The ability of women to organize was phenomenal, and one incredible example is that of the survivor Charlotte Delbo. When she was dying of thirst, her friends were able to help her get water to drink:

In the morning, clutching my companions, still mute, haggard, lost, I let myself be led—or rather they watched over me, since I was deprived of all reflex action, and without their help would have walked into an SS as easily as into a pile of bricks, or failed to keep my place in the ranks. I would have been shot… Carmen came back. She and Viva, having made sure the way was clear, grabbed me under each arm, taking me into a recess between a piece of wall and the pile of shrubs we were supposed to carry. “Here!” Carmen said, showing me a pail of water. It was made of zinc, like those used in the country to get water from a well. A large pail. Full. I tore myself from Carmen and Viva, threw myself on the pail of water. Actually fell upon it. I knelt near the pail and drank like a horse, dipping my nose in the water, plunging my whole face. (142-144)

The consequence that Delbo faced is clear; it was either death from thirst or death by bullet, both at the hands of the Nazis. However, Carmen and Viva helped get her to water, and helped her survive. This organization was essential to the survival of women. While getting water to their friend Charlotte was a form of resistance against the physical demolition of their bodies, cooking by imagination in Ravensbrück was a form of resistance against the psychological demolition of their minds.

[1] Translation of Käthe Anders, “Nie gelebt,” by Uma Kumar and William Orr, University of British Columbia, 2019.

Aftermath

Historians and Holocaust scholars now know a considerable amount about life in the concentration camps. This means that we now know more about the concentration camps than these artefacts alone can tell us. However, artefacts continue to add meaning to what camp life was like for prisoners. Specifically, these artefacts reveal how women resisted in the camps, and retrospectively, we know the larger danger that possessing these items posed. These concentration camps had extremely strict policies, to aid in the “demolition of man,” as Levi describes (22).

In addition to greater knowledge of the concentration camps, emphasis can now be placed on the female experience in the camps. As more research is done into the gendered experiences of the Holocaust, scholars are able to appreciate how women experienced the Holocaust differently than men. For instance, another aspect of female survival in the camps is the ability of women to survive together longer than men. Studies have shown that when put in extremely similar conditions to men, women could survive longer (Waxman 85). This is an aspect that Sybil Milton describes as the distinctly female means of survival in concentration camps after 1939:

Women had significantly different survival skills and techniques than did men. Although there were neither killing centres nor ghettos in Western Europe, German-Jewish women and those of other nationalities frequently used similar strategies for coping with unpredicted terror. Women’s specific forms of survival included doing housework as a kind of practical therapy and of gaining control over one’s space, bonding and networks, religious or political convictions, the use of inconspicuousness, and possibly even sex. Women appear to have been more resilient than men, both physically and psychologically, to malnutrition and starvation. (227)

Both the comb and the recipe book speak specifically to the last point made by Milton, regarding female resilience in concentration camps. One reason for this is that women were already experienced with organizing resources among each other, as this had been a large part of their home life before the Holocaust (Kaplan 200). It is these distinctly female aspects of camp life that aided in survival, something that is evident in the creation and use of these two artefacts.

Furthermore, women’s historians and cultural feminists have done extensive research into the ways that hair held significant meaning for the women who came into the camp. In Holocaust studies, that idea that the initiation into the camps was far more traumatic for the women than for the men is agreed upon in literature on the subject. As the female experience is continued to be studied as unique, Lillian Kremer highlights the ways in which initiation was different for men and women:

Men typically write of this experience in terms of loss of autonomy and personal dignity…his social status was obliterated. Women, socialized by religious teaching and communal values to be modest, experienced the process, and write of it, as a sexual assault during which they were shamed and terrified by SS men who made lewd remarks and obscene suggestions and poked, pinched, and mauled them in the course of delousing procedures and searches for valuables in oral, rectal, and vaginal cavities. (10)

This statement demonstrates how losing their hair was considered a form of violation comparable to sexual assault, or else often experienced in conjunction with sexual assault. Thus, this passage illustrates how the meaning of the comb as a form of resistance has changed over time. Not only was owning the comb itself an act of resistance, the meaning of it would have increased for a woman who experienced these types of assault upon entry to the camps. It would have been an item of resilience that was necessary for survival. In conclusion, it is clear that gender mattered during the Holocaust, not because their fate was different, but because each gender experienced the camp in distinctly different ways. The acts of creating a recipe book or owning a comb were ways to preserve this femininity that was shorn away from these women. In turn, the acts of creating and owning the comb and the recipe books were a form of distinctly female resistance.

Works Cited

Delbo, Charlotte. Auschwitz and After. Yale University Press, 1995.

Eichengreen, Lucille and Harriet Hyman Chamberlain. From Ashes to Life: My Memories of the Holocaust. Mercury House, 1994.

Anders, Käthe. “Nie gelebt.” Ich geb Dir einen Mantel, daß Du ihn noch in Freiheit tragen kannst, edited by Karin Berger, Promedia, 1987, pp. 97-106.

Comb, 1944. Vancouver Holocaust Education Centre. https://collections.vhec.org/Detail/objects/2017.

Levi, Primo and Marco Belpoliti. The Black Hole of Auschwitz. Polity Press, 2005.

Kaplan, Marion A. “Jewish Women in Nazi Germany: Daily Life, Daily Stuggles, 1933-1939.” Different Voices: Women and the Holocaust, edited by Carol Rittner and John K. Roth, Paragon House, 1993, pp. 187-212.

Karay, Felicja. Hasag-Leipzig Slave Labour Camp for Women: The Struggle for Survival, Told by Women and their Poetry. Translated by Sara Kitai. Vallentine Mitchell, 2002.

Kremer, S. Lillian. Women’s Holocaust Writing: Memory and Imagination. University of Nebraska Press, 1999.

Milton, Sybil. “Women and the Holocaust: The Case of German and German-Jewish Women.” Different Voices: Women and the Holocaust, edited by Carol Rittner and John K. Roth, Paragon House, 1993, pp. 213-249.

Saidel, Rochelle G. The Jewish Women of Ravensbrück Concentration Camp. University of Wisconsin Press, 2004.

Teitelbaum, Rebecca. Recipe Book, 1944 or 1945.Vancouver Holocaust Education Centre. https://collections.vhec.org/Detail/objects/7024.

Waxman, Zoë. “Concentration Camps.” Women in the Holocaust: A Feminist History, Oxford University Press, 2017, pp. 79-111.

Comments by Amanda Grey