By Abdul Hadi Ahmadi

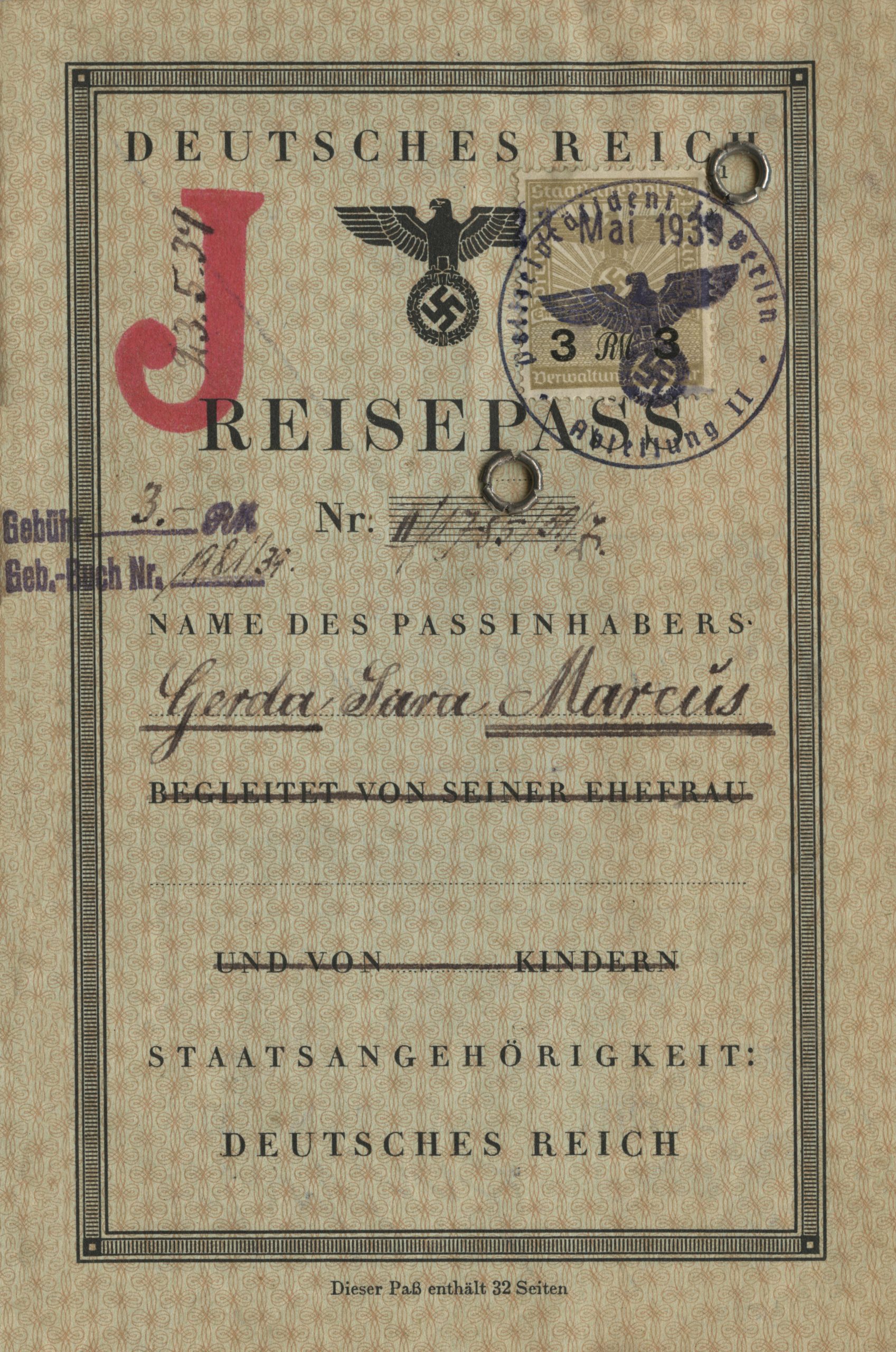

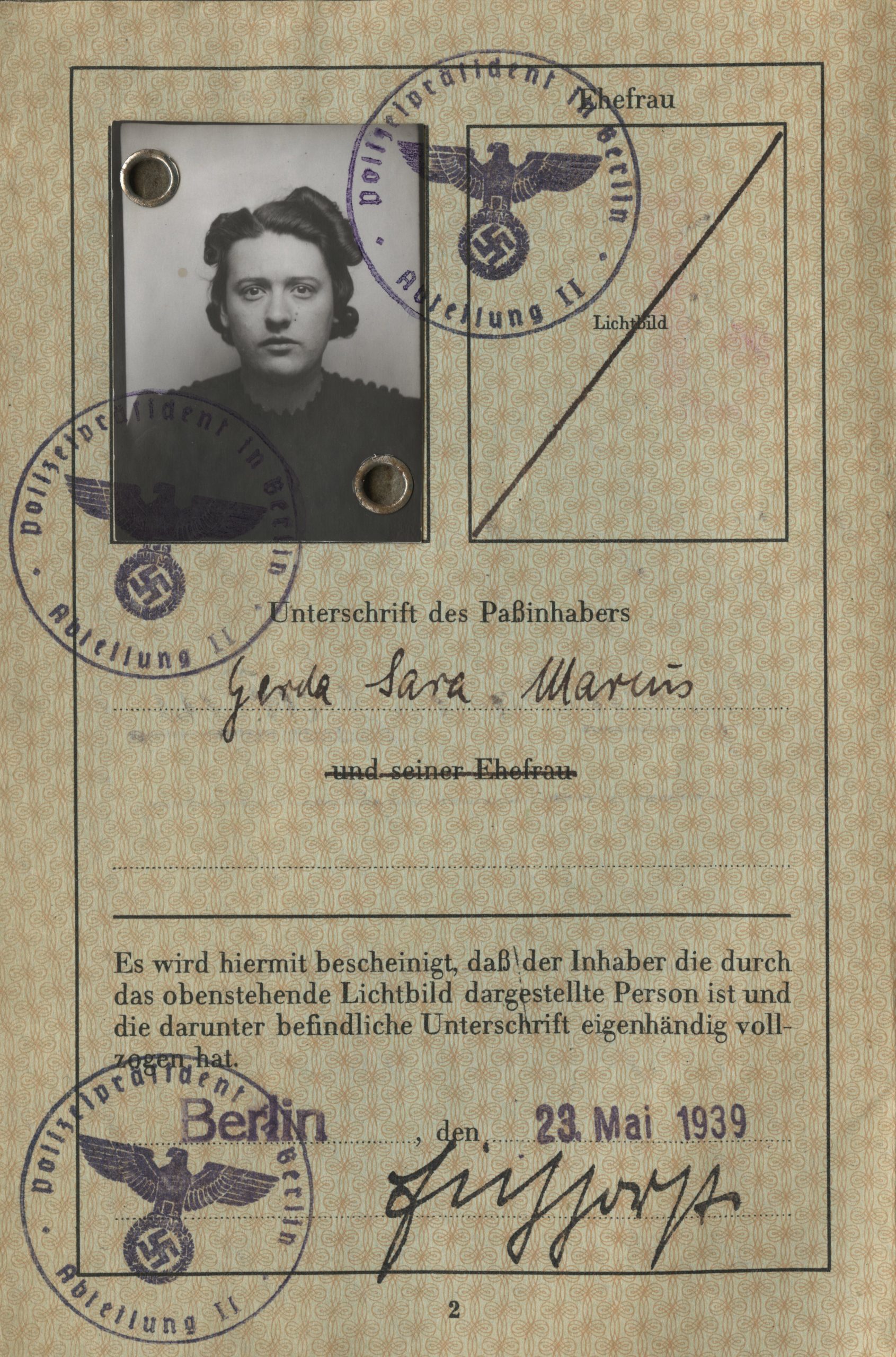

| Name of the Artefact | Star of David badge from Belgium | Deutsches Reich Reisepass |

| Creator | Unknown | Unknown |

| Date | 1942 | 1942 |

| Type | Cloth | Identification Document |

| Image |  |   |

| URL | https://collections.vhec.org/Detail/objects/1571 | https://collections.vhec.org/Detail/objects/1863 |

Artefacts and symbols play an essential role in illuminating the atrocities of the Holocaust. I have chosen to explore two artefacts from the Holocaust in the following essay. The first is a Star of David badge, and the second is a German passport (Deutsches Reich Reisepass), once belonging to Gerda Sara Marcus. Both artefacts are from the Vancouver Holocaust Education Centre (VHEC). These artefacts are essential in understanding, for example, how the Nazi regime identified who to arrest, isolate, torture, and dehumanize. I want to explain how these artefacts reflect the social, economic, and political conditions of the Jewish people during the Holocaust. To achieve this, I will explore the meaning, origins, aftermath, and the symbolism of these two artefacts.

Star of David Badge from Belgium

Overview

The first artefact is a Star of David badge that was made in 1942. This is a printed six-pointed star on yellow cloth that was sewn onto another piece of cloth. All Jewish people had to wear this badge in Nazi Germany and the occupied countries during the Third Reich.

Meaning

The meaning of the Star of David badge during the Third Reich is interconnected with its historical background. The Star of David, or in Hebrew the Magen David (“Shield of David”), “[is a] Jewish symbol composed of two overlaid equilateral triangles that form a six-pointed star” (Encyclopaedia Britannica). The cultural symbolism of the star is rooted in the belief that the Jewish population is holy. During the Holocaust, the Star of David symbol was recontextualized by the Nazis and was stamped on badges in order to identify Jewish people.

Symbolism

In Jewish culture, the Star of David is a traditional and religious symbol of hope and courage. It is also a symbol of protection against evil spirits. The Jewish community of Prague was the first to use the Star of David as its official symbol. One can draw comparisons to Christianity where the Cross is a principal symbol, or to Islam in regard to the Crescent moon and star (Encyclopaedia Britannica). The historical origins of the Star of David badge also reveal that wearing the badge for identification purposes was not exclusive to the Nazi era. This technique (the wearing of a badge) had been previously used to systemically isolate and segregate Jewish people. In the 8th century, the Caliph Haroun al Rashid (a Muslim ruler) ordered Jewish people to wear yellow belts. The mark of identification “was meant to both reinforce the dhimmi (protected religion) status of Jews and Christians, which gave them certain rights and protections while at the same time publicly branding them as socially inferior to Muslims” (United States Holocaust Memorial Museum). The Star of David was also present in medieval times when different civilizations used it as an ornamental sign. In the nineteenth century, Jewish people began to use the “Star of David as a religious or national symbol” (qtd. in Kanfer). However, the lives of all German-Jewish people changed dramatically after the Nazi regime came to power. The Nazis boycotted Jewish businesses; they painted the Star of David in yellow and black on the doors and windows of all Jewish businesses with signs saying “Don’t Buy from Jews,” and “The Jews Are Our Misfortune” (United States Holocaust Memorial Museum).

Aftermath

In September 1941, the Nazi party introduced legislation that all Jewish citizens need to wear a yellow star with the letter “J” on it in order to be identified by the Gestapo and the SS (Kanfer). This German legislation was “one of many psychological tactics aimed at isolating and dehumanizing the Jews of Europe, directly marking them as being different (i.e., inferior) to everyone else” (Arsenault). The wearing of the yellow star by Jewish people allowed the Nazis to quickly identify who was Jewish. As Lucille Eichengreen states in her book Ashes to Life, “Jewish adults and children alike had been ordered by the Germans to wear the yellow star on their coats. We were now even more easily identified as objects for beating, ridicule, and harassment” (34). The yellow star during the Holocaust was not only a way to separate Jews from the rest of the population, but it was also used as a method of public shaming in order to degrade a particular religion and race. In her book, Still Alive: A Holocaust Girlhood Remembered, Ruth Kluger clearly describes this fear that the wearing of the star brought upon her: “the cinema was a magnet, and on occasion, I would simply go to a film without wearing the star. I did not tell my mother and carefully chose theaters in the busy inner city, where no one would know me” (41).

The meaning and symbolism of these artefacts have dramatically changed over time. During the Holocaust, wearing the yellow star made it easy for Nazis to identify and arrest, humiliate, and degrade the Jewish people. Although Jewish people had their own signs and dress as a part of their traditions, the atmosphere cultivated by the Nazis made the wearing of this star unpleasant and shameful. These feelings are illustrated by Yedida Kanfer: “what Jews wore willingly usually did not have a negative connotation but as soon as clothes or badges were forced upon them, they became marks of shame.” Despite the suffering and degradation that the Jewish people experienced by wearing the yellow badge during the Holocaust, the Star of David still stands as a symbol of courage and resistance. In fact, many survivors see it as a symbol of resistance, pride, and persistence. Kanfer, in her article “What is a Symbol,” refers to the yellow star as a symbol of hope: “[t]he Star of David [is] a symbol of hope for an end to Jewish persecution.” Also, in the testimony of Jannushka J., she describes how she suffered from being Jewish under the Nazi regime. Her photograph, which was taken in 2010 by the Vancouver Holocaust Education Centre, reveals that she holds the yellow star badge with confidence and pride (Figure 3). I believe, along with Kanfer, that the history of the Star of David badge shows the strength and flexibility of symbols over history. Moreover, the influence of social movements and public emotions towards a religious or social group has a great ability to change and manipulate symbols and utilize them to justify political actions.

Deutsches Reich Reisepass

Overview

The second artefact is a Deutsches Reich Reisepass (German passport) issued in both German and English in 1942. This travel document was preserved and maintained by Bedrich Eisinger (birth name Fritz Eisinger, born June 21,1905 in Vienna, Austria) and his wife Gerda Eisinger (birth name Gerda Sara Marcus, born April 16, 1916 in Berlin, Germany) until 1980. It was donated by Barbara Eisinger to the Vancouver Holocaust Education Centre in 2013.

Meaning

Travel documents that were stamped on the first page with the red letter “J” were used to identify Jewish citizens. Jewish people were labelled and marked by the Nazi regime in various ways; this was done in order to segregate them from businesses and economic activities beginning in 1933. In 1938, the German government decreed that all male and female Jewish people were required to add the name “Israel” and “Sara” onto their identification documents. Due to this law, Jewish people had to carry identity cards or passports stamped with the letter “J.” These methods were effective at permanently segregating them from the rest of the population (United States Holocaust Memorial Museum). According to Primo Levi, “[f]rom the age of six upwards, they had to wear the yellow star on their chest. They could only sit on public benches, which had Nur für Juden (only for Jews) written on them. All men had to be called Israel, and all women Sara… this was the prologue to their total exclusion from economic life” (56).

Symbolism

The Nazi regime deliberately used the letter “J” on travel documents and identification cards in order to restrict the free movement of Jewish people. Ernest Heppner highlights this in his memoir, Shanghai Refuge: A Memoir of the World War II Jewish Ghetto: “When I mentioned that I intended to go over the border, my father pointed out that I would not get very far, since the large “J” in my passport was a dead giveaway” (Heppner 28). The letter “J” on identification documents created fear and hostile behavior against Jewish people from multiple European countries. For example, “some of the other emigrants and I wanted to go ashore, but when the British officials saw the red letter “J” on our passports, they became uncooperative” (Heppner 32). Stamping a “J” on Jewish travel documents was a part of the Nazis’ systematic measure to restrict, isolate and humiliate the Jewish population.

Aftermath

The red “J” that simplified the process of identifying Jewish people under German Nazi rule has continued to have ramifications on the social and cultural relationships of Jewish people living in Germany. Oshrat Hochman and Sybille Heilbrunn’s research on Jewish identification suggests that after the Holocaust, Jewish people have employed cautionary social behavior while integrating into contemporary German society. They write: “We would like to stress the critical role of context in the selection of integration strategies: in Germany, the maintenance of Jewish culture contradicts the accepted notion of German-ness. In Israel, however, the participants describe freedom to practice their German culture that does not hamper their acceptance as (Jewish) Israelis” (Hochman and Heilbrunn). The role of these artefacts demonstrates that racism and fascism in the contemporary world are the most harmful elements that lead society to disaster.

In conclusion, these two artefacts contribute to the message that persecution of people based on their religion and race not only fails to “Demolish Men,” as Levi writes, but can amplify the movement of resistance. These artefacts give awareness that can help deconstruct the Nazis’ harmful ideology. These artefacts, as primary evidence, allow us to understand what happened in the past. These artefacts also open our eyes to fascism and racism in the contemporary world. As Kluger writes, “[i]n our hearts we all know that some aspects of the Shoah have been repeated elsewhere, today and yesterday, and will return in new guise tomorrow” (75). For example, atrocities against Burma’s Rohingya population that have resulted in the fleeing of 700,000 people to Bangladesh since 2017 exposes the unpleasant reality that race superiority and prejudice still continues. Many artefacts carry a long story of the individual under persecution; thus, they are not only placed behind an exhibition screen for visitors to watch, but each of them is a silent storyteller that conveys the time of the artefacts to the soul and mind of visitors.

Works Cited

Arsenault, Joshua, ed. “Jewish Stars and Other Holocaust Badges.” Holocaust Memorial Center, https://www.holocaustcenter.org/visit/library-archive/holocaust-badges/. Accessed 08 May 2020.

The Editors of Encyclopedia Britannica. “Star of David.” The Encyclopedia Britannica, 3 Jan. 2020, https://www.britannica.com/topic/Star-of-David

Eichengreen, Lucille, and Chamberlain Harriet Hyman. From Ashes to Life: My Memories of the Holocaust. Mercury House, 1944.

Eisinger family. Deutsches Reich Reisepass. 1939. Vancouver Holocaust Education Centre. https://collections.vhec.org/Detail/objects/1863.

Heppner, Ernest. Shanghai Refuge. A Memoir of the World War II Jewish Ghetto. Plunkett Lake Press, 2018.

Hochman, Oshrat, and Sibylle Heilbruun. “‘I Am Not a German Jew. I Am a Jew with a German Passport’: German-Jewish Identification among Jewish Germans and Jewish German Israelis.” Identities: Global Studies in Culture and Power, vol. 25, no. 1, 2018, pp. 104-123.

Gettleman, Jeffrey. “Rohingya Recount Atrocities: ‘They Threw My Baby Into a Fire.’” The New York Times.11 Oct. 2017.

Kanfer, Yedida. “What Is a Symbol? The Corruption and Reclaiming of the Jewish Star.” Jewish Family and Children’s Services Holocaust Center, https://holocaustcenter.jfcs.org/what-is-a-symbol/. Accessed 08 May 2020.

Kluger, Ruth. Still Alive: A Holocaust Girlhood Remembered. Feminist Press, 2001.

Levi, Primo. The Black Hole of Auschwitz. New York: Polity Press, 2005.

Star of David badge from Belgium. 1942. Vancouver Holocaust Education Centre. https://collections.vhec.org/Detail/objects/1571

United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. “Jewish Badge: Origins.” Holocaust Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/jewish-badge-origins. Accessed 08 May 2020.

Comments by Amanda Grey