By Isabella Devereaux

| Name of the Artefact | Winterhilfswerk Oberdonau region folk costume pin | 5 Kronen Scrip from Theresienstadt |

| Creator | Nationalsozialistiche Volkswohlfahrt (National Socialist People’s Welfare) | Bank der jüdischen Selbstverwaltung (issued by) Kien, Petr (designed by_ |

| Date | 1933 – 1945 | January 1st, 1943 (date issued) |

| Type | Pin | Currency, Medals and Militaria |

| Image |   |   |

| URL | https://collections.vhec.org/Detail/objects/6701 | https://collections.vhec.org/Detail/objects/2887 |

Winterhilfswerk Oberdonau region folk costume pin

Overview

The first artefact is a pin created by the Nationalsozialistiche Volkswohlfahrt Organization or the National Socialist People’s Welfare Organization. The National Socialist People’s Welfare Organization was a German social welfare organization and the second largest Nazi group organization. The pin is embroidered, depicting a female in a “traditional folk dress from the Oberdonau region” (Winterhilfswerk Costume Pin). The Oberdonau region was the Nazi administrative division in Upper Austria. The dress the woman is wearing is blue, red, white, and green; she is standing in a field of flowers and green grass, in front of hills. The pin is framed by a painted light blue metal frame. The materials used are embroidered rayon and a painted metal frame.

The Vancouver Holocaust Education Centre has multiple pins similar to this one in their collection. Each pin depicts a different traditional German scene. In Germany, pins such as these were exchanged for a donation to the Winterhilfswerk des Deutschen Volkes (Winter Relief of the German People). The Winterhilfswerk des Deutschen Volkes had a yearly campaign to raise money for the Nationalsozialistische Volkswohlfahrt (National Socialist People’s Welfare Organization). This pin was created between 1933 and 1945 by the Nationalsozialistische Volkswohlfahrt. The organization created different Nazi propaganda objects every week from October through March to encourage donations.

Meaning

According to the Vancouver Holocaust Education Centre, these pins were used to raise money for the Nazi party. The Nationalsozialistische Volkswohlfahrt supported the “Nazi concept of Volksgemeinschaft, where citizens would forfeit personal comforts for the greater good of the … German people” (Winterhilfswerk Costume Pin). The selling of these pins funded the efforts of the Nazi party and agenda. Thus, by raising money for the Nazi party, the lives of Jewish people were affected negatively. Without the support of the German people, both monetary support and political support, the Nazi party would not have been successful for as many years as they were.

Symbolism

The Winterhilfswerk Oberdonau region folk costume pin represents the support of the German citizens for the Nazi party, and especially the support of German women. In her book Hitler’s Furies: German Women in the Nazi Killing Fields, Wendy Lower discusses the contribution that German women made during the Holocaust, which is often overlooked in literature. In Mein Kampf, written by Adolf Hitler and published in 1925, Hitler identifies himself and his reader as “National Socialists.” There was a clear and obvious tie between the Nationalsozialistische Volkswohlfahrt, or the National Socialist People’s Welfare Organization, and Hitler and his goals.

Among the members of the National Socialist People’s Welfare organization was Pauline Kneissler, who was a “better-known … German nurse-killer” (Lower 50). She was also a member of other Nazi organizations such as the National Socialist Women’s League, the Reich Air Raid Protection League, and the Reich Nurses League (50). Kneissler became a “career killer” at euthanizing sites across Germany (52). She assisted with the “gassing procedure, starving patients, and administering lethal injections to the mentally and physically ill almost every day for five years” (52). This testimony from Lower highlights the members of the Nationalsozialistische Volkswohlfahrt and their impacts in the Nazi effort.

By identifying the actions of certain members of the Nationalsozialistische Volkswohlfahrt, Lower exposes the members of this organization of Nazis and their actions. In other words, members of the Nationalsozialistische Volkswohlfahrt were Nazis and were complicit in the Nazi efforts. The Vancouver Holocaust Education Centre states that the Nationalsozialistische Volkswohlfahrt did not provide services or aid to Jewish people or any other group that was “not considered part of the Aryan race” (Winterhilfswerk Oberdonau Region Folk Costume Pin). The selling of these pins directly funded the Nazi agenda.

Hilde Sherman also speaks about the role that ordinary German citizens had in the Holocaust. Sherman, a Holocaust survivor, recounts her experience with her transport to the Riga Ghetto in 1941. She claims that German citizens watched through their windows as over one thousand Jews were transported to the ghetto (“From the Testimony of Hilde Sherman”). Sherman writes that “no one can claim that they did not see. Of course they saw us” (“From the Testimony of Hilde Sherman”).

Sherman’s testimony sheds light on the complicity of the German public during the Holocaust. German citizens, like members of the Nationalsozialistische Volkswohlfahrt, are often not labeled as direct perpetrators in the Holocaust. However, Sherman’s testimony highlights that these citizens were indeed complicit in the Holocaust. This complicity can be compared to the German citizens who sold and bought the folk costume pins. By selling or buying these pins, citizens directly supported the Nazi party, and therefore their agenda of exterminating the Jewish people.

In addition, these pins highlight the culture of the German public during the war. The Nationalsozialistische Volkswohlfahrt raised money for their nation’s army. Additionally, these pins shed light on the German concept of Volksgemeinschaft, where German citizens were supposed to “forfeit personal comforts for the greater good” of the German people.

Aftermath

Today, the meaning of the pins has not changed. They are seen as a symbol of German culture.

5 Kronen Scrip

Overview

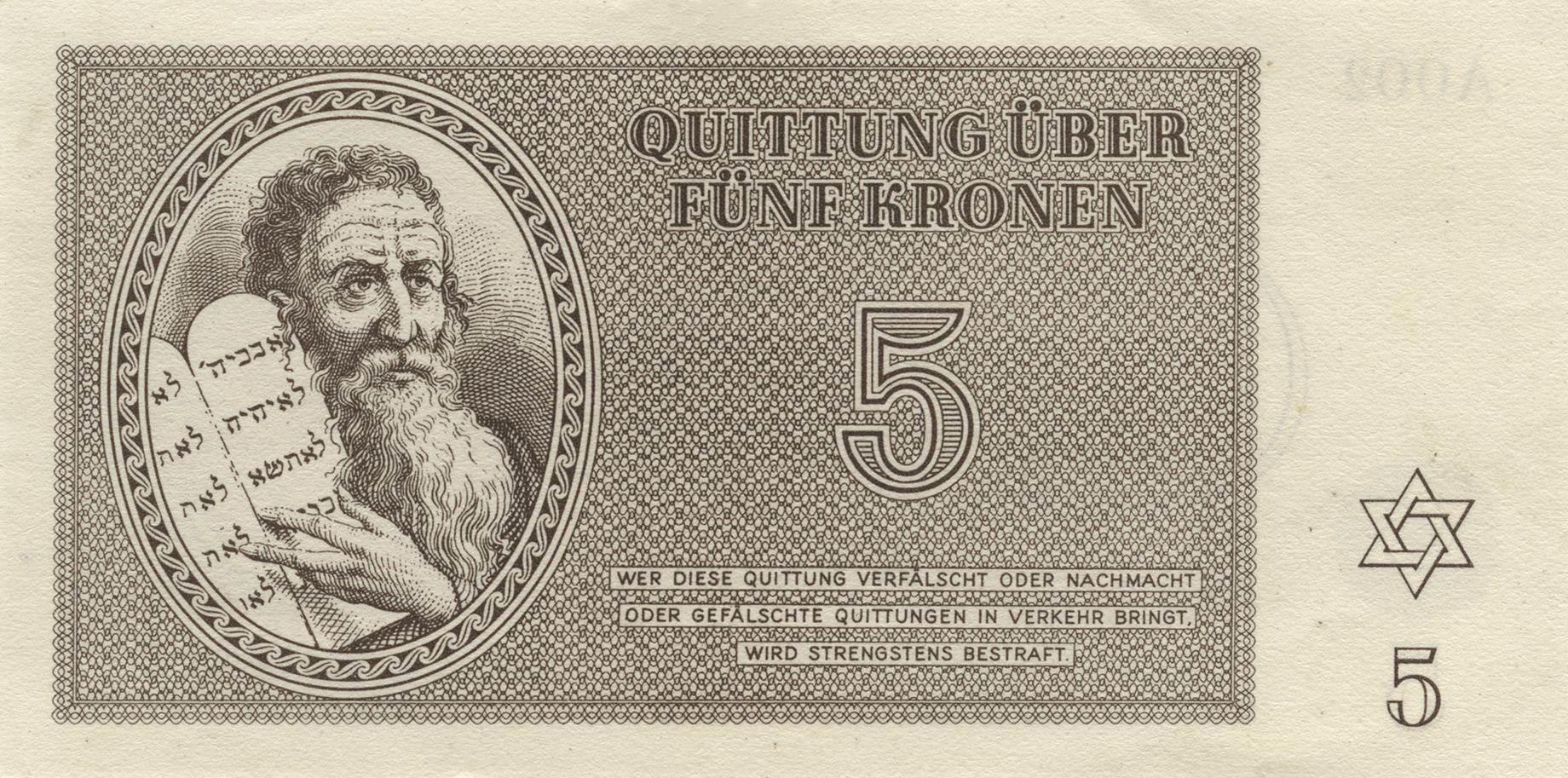

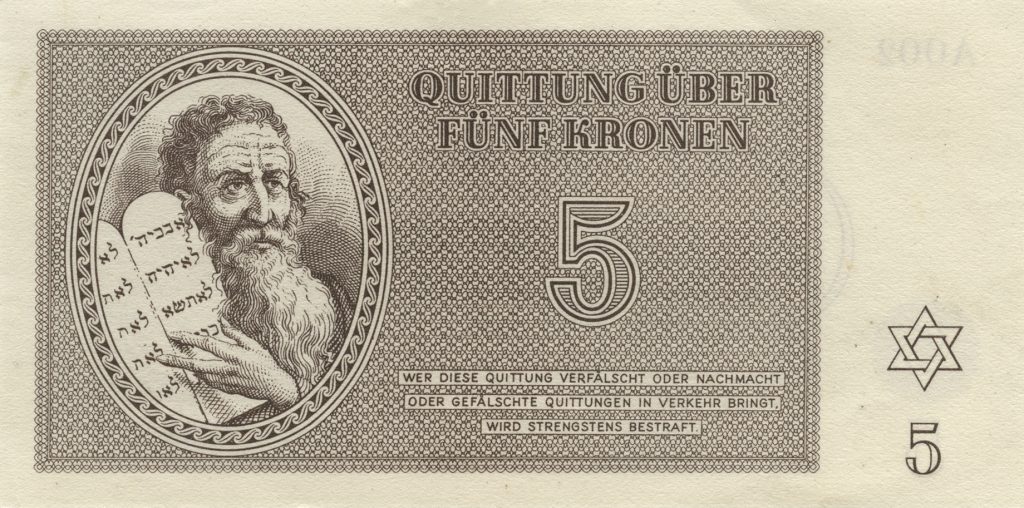

The second artefact is a 5 krone note issued in Theresienstadt, a concentration camp and ghetto that was active during the Holocaust. This artefact is printed on white paper with brown, black, and red ink, with the dimensions of 5.8 by 11.8 centimeters. This artefact is in the category of “currency, medals and militaria.” This artefact was gifted to the Vancouver Holocaust Education Centre by Joseph Segal. The date of creation was January 1st, 1943, which is the date the note was issued. It was created by the Bank der jüdischen Selbstverwaltung, and was designed by Petr Kein. It was created within the Theresienstadt ghetto. According to the Vancouver Holocaust Education Centre, this note had very little economic value. The only real purpose of the note was to pay taxes for packages entering the camp. This bill, and those like it, was used to make Theresienstadt seem normal. Theresienstadt was a “propaganda tool” by the Nazi regime, as they used Theresienstadt to attempt to show the world that they were treating the Jewish people well within the camps (5 kronen scrip). This, as we know, is not true. In Theresienstadt, Jewish people were not treated well to any extent.

Meaning

As previously stated, this 5 krone note did not have much economic value. According to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, while the living conditions within Theresienstadt were deplorable, Theresienstadt “had a highly developed cultural life.” Because of this, Theresienstadt was used to prove to the world that the Nazis were treating the Jewish people well. Publicly, the Nazis stated that the purpose of the deportation of the Jewish people was “resettlement to the east,” where they would be compelled to perform forced labor” (“Theresienstadt”). The Nazis claimed that Theresienstadt was a “‘spa town’ where elderly German Jews could ‘retire’ in safety” (“Theresienstadt”). The use of the “krone note” was part of the propaganda that the Nazis used to convince the global public that Theresienstadt was a safe place for Jewish people.

Symbolism

This krone note shows the extent to which the Nazi regime went to hide the atrocities that they were committing. Ruth Kluger’s autobiography, Still Alive: A Holocaust Girlhood Remembered, recounts her experience growing up during the Holocaust. Kluger spent time in Theresienstadt and discusses the community that she experienced with the other Jewish people within the ghetto, retelling the story of elderly Jewish people teaching the younger people Jewish culture and religion. Kluger claimed that “the ghetto believed in culture” (86). In her account, however, the positive aspects of the ghetto are far outweighed by the negative aspects. Kluger states that “Theresienstadt … was the stable that supplied the slaughterhouse” and that “almost 140,000 people were deported to that ghetto, and less than 18,000 were liberated at war’s end” (70). Her testimony highlights the extent to which Theresienstadt was a propaganda tool used by the Nazis. In reality, it was a place to put Jewish people before they were sent to extermination camps like Auschwitz, which is where Kluger was sent after Theresienstadt. It should be noted that the Jewish people in Theresienstadt found community and culture at a time where everything was taken away from them. In her writings, Kluger successfully shows the strength and resilience of the Jewish people in the ghettos and camps.

This krone note can also shed light on how the Nazis used other Jewish ghettos. After Theresienstadt, the Riga and Lodz ghettos were famous Jewish ghettos during the Holocaust. In Hilde Sherman’s recount of her time in the Riga ghetto, she describes the scene of the house she lived in. The morning after she arrived in the house, she noticed that “there was a table that was set. There were plates, cutlery, cups, and most astonishingly, bowls of prepared food. However, they were frozen.”[1] This quote from Sherman highlights many things about life within the Riga ghetto. Most importantly, it shows that Sherman was placed in a home that had been inhabited before her. It shows that the people who lived there were abruptly taken out of their homes. This was a trend within Jewish ghettos. The Nazis had a cycle of transporting Jews to the ghettos to replace the Jews that had been sent to the extermination camps.

Lucille Eichengreen, a survivor of the Lodz ghetto, describes the deplorable living conditions that the Jewish people had to survive in the ghettos. Eichengreen claims that single rooms housed five to eight people. Their rooms had no form of heating and only had their clothing to keep warm (38). The lack of hygiene available meant that many people died from disease within the ghettos. Eichengreen’s own mother died of starvation in the Lodz ghetto (139).

The krone note artefact from Theresienstadt gives us a look into what the Jewish ghettos were like. From examining life in Theresienstadt, we can then examine life in the other Jewish ghettos. In addition, we can better understand and compare the conditions in Theresienstadt, which was supposed to be a “spa” for Jewish people, to the conditions in other ghettos.

[1] Translation of Hilde Sherman, Zwischen Tag Und Dunkel. Mädchenjahre Im Ghetto, by Uma Kumar, University of British Columbia, 2019.

Aftermath

The importance and meaning of this artefact has not changed much over time. What was once used to hide the mistreatment of millions of Jewish people is now evidence of the mistreatment of the Jewish people. It shows the extent to which the Nazi regime went to hide their actions to the global community. This artefact is important because it shows that the Nazis knew that what they were doing was wrong. By hiding their actions from the global public, creating propaganda like the krone note and the falsely positive conditions in Theresienstadt, the Nazis attempted to hide their actions in order to continue their tyranny.

Works Cited

5 Kronen Scrip from Theresienstadt. 1 January 1943. Vancouver Holocaust Education Centre, collections.vhec.org/Detail/objects/2887.

Eichengreen, Lucille, and Harriet H. Chamberlain. From Ashes to Life: My Memories of the Holocaust. Mercury House, 1994.

“From the Testimony of Hilde Sherman about the Deportation to Riga and the Arrival to the Ghetto.” Yad Vashem Archives, The International School for Holocaust Studies, https://www.yadvashem.org/odot_pdf/Microsoft%20Word%20-%203287.pdf. Accessed 07 May 2020.

Klüger Ruth. Still Alive: a Holocaust Girlhood Remembered. Feminist Press at the City University of New York, 2012.

Lower, Wendy. Hitler’s Furies: German Women in the Nazi Killing Fields. Mariner Books, 2014.

“Rallying the Nation.” United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Holocaust Encyclopedia, United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/rallying-the-nation.

Sherman, Hilde. Zwischen Tag Und Dunkel. Mädchenjahre Im Ghetto. Ullstein, 1989, pp. 35–41.

Smith, C. A. “On The National Socialist Organisation, NSV: Ns-Peoples Welfare: Propaganda And Influence From 1933 To 1945.” German History, vol. 4, no. 1, Jan. 1987, pp. 62–63, doi:10.1093/gh/4.1.62.

“Theresienstadt.” United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Holocaust Encyclopedia, United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/theresienstadt.

Winterhilfswerk Oberdonau Region Folk Costume Pin. 1933-1945. Vancouver Holocaust Education Centre, collections.vhec.org/Detail/objects/6701.

Comments by Amanda Grey