By Khian Tan

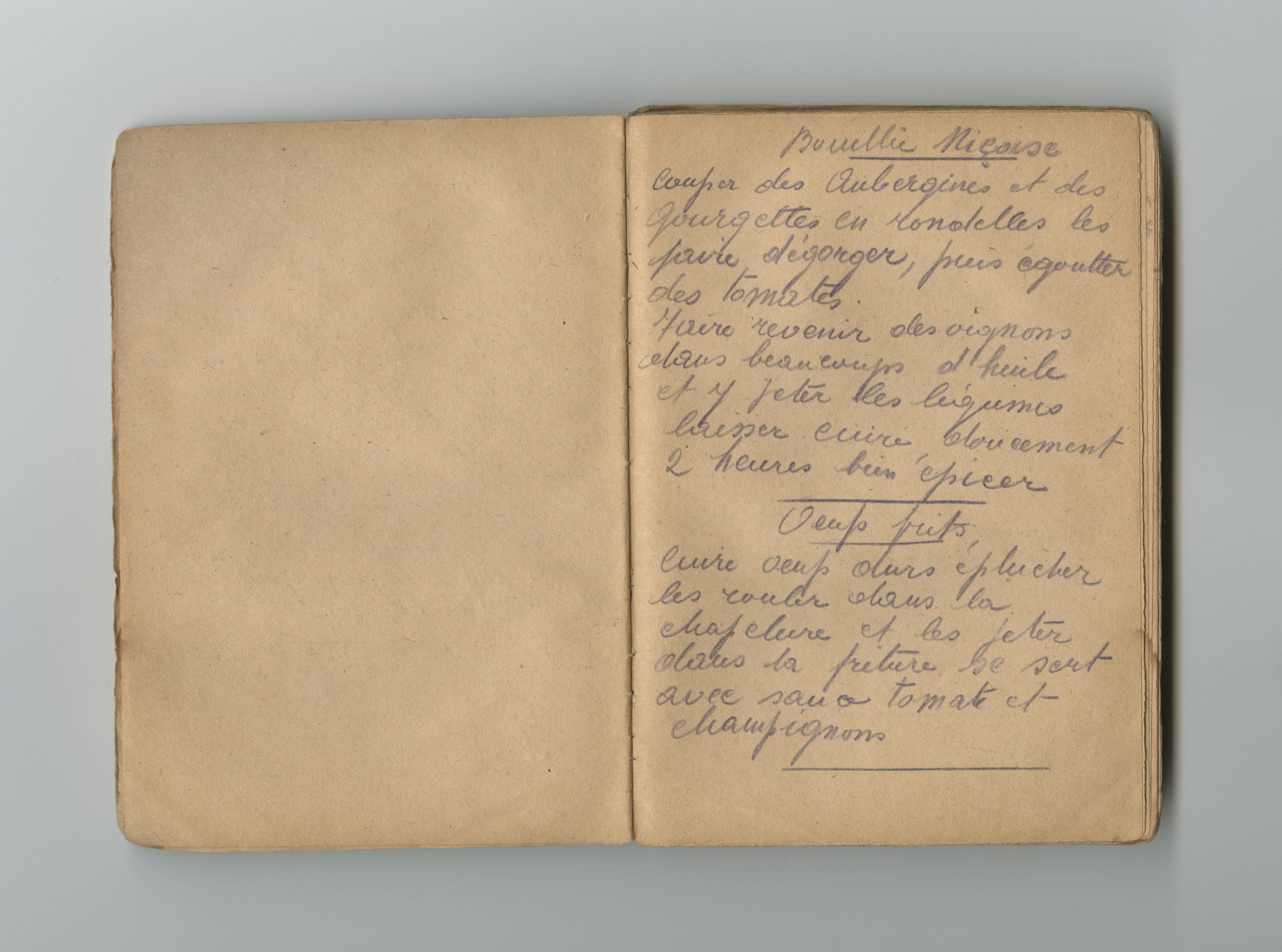

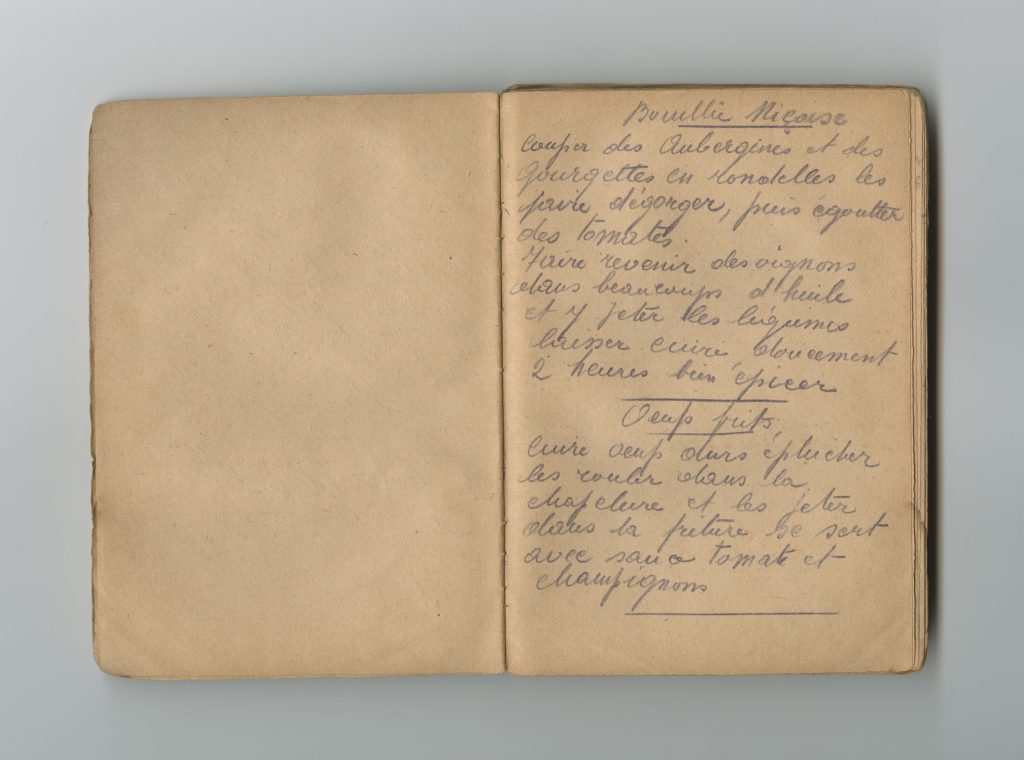

| Name of the Artefact | Star of David badge belonging to Renia Perel | Recipe Book |

| Creator | Unknown | Teitelbaum, Rebecca |

| Date | Unknown | 1944 or 1945 |

| Type | Cloth, dye, ink | Paper, text, thread |

| Image |  |  |

| URL | https://collections.vhec.org/Detail/objects/7574 | https://collections.vhec.org/Detail/objects/7024 |

Star of David badge belonging to Renia Perel

Overview

According to the website of the Vancouver Holocaust Education Centre (VHEC) Collections, the Star of David badge belonging to Renia Perel is a rectangular yellow cloth badge with a 6-pointed Star of David. While we know that the artefact is made with materials such as cloth, dye and ink, the creator and date of creation of this artefact are unknown. This artefact was used as a source of identification of Jewish people living under Nazi rule. The artefact was donated to the VHEC in 2019 by Carmen S. Thériault, Trustee of the Renia Perel Trust.

Meaning and Symbolism

Origins

The yellow Star of David badge was originally created by Muslim rulers back in the 8th Century CE for the purpose of identifying Jews and Christians, giving these Jews and Christians certain rights and protections and publicly classifying them as socially inferior to Muslims (“Jewish Badge: Origins”).

In the context of the Holocaust, the badge was used again from 1938 to 1945 as a form of identification of Jewish people, with more negative and extreme symbolisms than during its previous use (to be discussed later). By the fall of 1941, all Jewish people were required to wear the Yellow Star of David badge to identify themselves explicitly as Jews (Lucille Eichengreen; Ruth Kluger). Even when Jewish people were in ghettos and concentration camps, it was still mandatory for them to wear these badges, as is evident in the descriptions of Heinz Heger, Hilde Sherman, and Lucille Eichengreen.

Beyond identifying and labelling Jewish people, the yellow Star of David badge also had very negative and extreme symbolisms. Two of these such negative symbolisms were segregation and discrimination. These are presented by Ruth Kluger, as she describes the 1940s in Vienna as having “rampant” discrimination, adding that Jewish people wearing the yellow Star of David badge were not allowed to “go on excursions or into museums” (25). This shows how the badges segregated the Jewish people by restricting them from public spaces, disallowing them to be part of the general Austrian population. With the badge, the Jewish people were discriminated against more easily and conveniently.

In addition, the yellow Star of David badge also symbolised the dehumanisation of the Jewish people. This symbolism is presented by Eichengreen when she describes how the yellow Star badge “identified [the Jews] as objects for beatings, ridicule and harassment” (34). The badge thereby contributed to dehumanization, so that the Jewish people who wore the badge received mistreatment such as being persistently harassed and physically and psychologically tormented.

It is also important to note that even the Jewish ghetto police had to wear the yellow Star of David badge, as Sherman-Zander and Eichengreen describe in their books. This shows that while certain Jewish people were privileged relative to others, and could avoid some punishments by the Nazis, all Jews were still heavily discriminated against by the Nazis.

Aftermath

Today, having gone through the horrors of the Holocaust, some survivors view the Star of David as “a symbol of resistance, courage, and national continuity” (Holocaust Centre). Similar to the survivors’ testimonies that we read today, the Star of David is a symbol of the times of difficulty and hardships that the Jewish victims of the Holocaust have gone through. The star also helps to commemorate and signify that Jewish traditions remain ongoing despite attempts by the Nazis to erase them.

Recipe Book

Overview

As described on the website of the Vancouver Holocaust Education Centre (VHEC) Collections, the creator of the recipe book was Rebecca Teitelbaum, and the artefact was made using paper, needles, and thread. Its recipes included Mousse au Chocolat, Gelée de Groseilles, Gâteau Neige, Plat Hongrois, Ouef Hollandais, Sabayon Italien and Rebecca Teitelbaum’s own Gâteau à l’Orange. All the recipes were written in French, though the contents of the recipe book have been partially translated. The date of creation of this artefact is between 1944 and 1945.

Meaning

During the times of hardship and dehumanization in the concentration camps, the Jewish inmates, especially the women, saw recipe books as contributing to a sense of community, family, and even identity, since food preparation strongly related to women’s prewar domestic identity (Vasvari). This is evident in Louise Vasvari’s descriptions, which note that the handwritten recipes allowed Jewish women in the concentration camps to restore their sense of identity, in that they would share various recipes and memories of their families with each other. In other words, recipe books helped to counter the constant dehumanisation caused by the conditions of the concentration camps. Working on these recipe books reminded the women of their identities and roles as Jewish women.

Furthermore, working on these recipe books also allowed for moments of enjoyment and relaxation for the inmates. This is evident in Kluger’s descriptions, where she writes of the women in the slave labor camp in Christianstadt who always had “fantasy baking contests” (122) among themselves. The “contests” that these inmates organized among themselves demonstrates the positive interactions generated by and associated with the recipe books. Thus, the recipe books brought the inmates times of positivity amidst the difficulty of the concentration camps.

The sense of identity and community that was spurred by the recipe books also allowed female Jewish inmates to develop a strong sense of resilience in the face of hardship. Devra Ferst’s article on cookbooks from the Holocaust presents the thoughts of Holocaust survivors: during their time in the concentration camps, the recipe books conjured up memories of their families, which helped them psychologically to overcome the hardships they faced. These survivors also viewed the recipes in the recipe books as a way of sustaining their Jewish traditions (Ferst). This suggests that the recipe books were also sources of tenacity and strength for these women to survive and also pass down their Jewish culture and traditions to future generations.

Symbolism

Origins

When the recipe books were initially created, it seemed they were created only for the purpose of recalling memories in the concentration camps. However, these recipe books then symbolized “an important psychological act of resistance” (Ferst). It is important to note, however, that this type of resistance (recipe books) is vastly different from the one described by Primo Levi. Levi’s descriptions of resistance were mostly physical and violent uprisings, where the inmates would be armed with weapons and guns.

In contrast, the recipe books symbolized a type of spiritual and psychological resistance, wherein Jewish inmates would write down Jewish recipes to preserve and pass on the tradition and culture. This type of resistance is similar to those described by Eichengreen and Kluger: Eichengreen describes the Łódź ghetto as having small ghetto schools hidden away in factories, where the younger Jewish inmates could receive an education and some extra food. Kluger describes an art historian and a teacher who taught the Jewish inmates in Theresienstadt about art history. These acts of spiritual and psychological resistance were, of course, forbidden and would be met with punishments if they were discovered by the Nazi guards. This was because such acts were means of passing down Jewish traditions and culture, which were what the Nazis tried to destroy.

Thus, the recipe books symbolized spiritual as well as psychological resistance against the Nazi regime—means of preserving and passing down Jewish culture and traditions in written form.

Aftermath

The roles of these recipe books changed vastly even during the times of the Holocaust. Starting out as a source of community and identity, the recipe books moved on to become acts of spiritual and psychological resistance. Today, these recipe books not only present Jewish culinary traditions, they also remind us of the stories of Holocaust survivors and the unpleasant times they went through as victims (Ferst), much like the yellow Star of David badge. As stated in Norene Gilletz’s article, “Recipes Seasoned with Bittersweet Memories,” these recipe books “ensure that the stories of these brave survivors will live on for generations to come” and that we should “remember the history they contain.”

Works Cited

Eichengreen, Lucille, and Harriet Hyman Chamberlain. From Ashes to Life: My Memories of the Holocaust. Mercury House, 1994.

Ferst, Devra. “Holocaust-Themed Cookbook Recalls Darker Days.” Forward, 13 July 2011, https://forward.com/life/138605/holocaust-themed-cookbook-recalls-darker-days/. Accessed 14 May 2020.

Friedman, Ina. The Other Victims: First-Person Stories of Non-Jews Persecuted by the Nazis. Houghton Mifflin Co, 1990.

Gilletz, Norene. “Recipes Seasoned with Bittersweet Memories – The Holocaust Survivor Cookbook.” Orthodox Union, 1 May 2008, https://www.ou.org/life/food/recipes_seasoned_with_bittersweet_memories_the_holocaust_survivor_cookbook/. Accessed 14 May 2020.

Heger, Heinz. The Men with the Pink Triangle: The True Life and Death Story of Homosexuals in the Nazi Death Camps. London: Gay Men’s Press, 1980.

Kanfer, Yedida. “What Is a Symbol? The Corruption and Reclaiming of the Jewish Star.” Jewish Family and Children’s Services Holocaust Center, https://holocaustcenter.jfcs.org/what-is-a-symbol/. Accessed 08 May 2020.

Kluger, Ruth. Still Alive: A Holocaust Girlhood Remembered. The Feminist Press at CUNY, 2003.

Levi, Primo. The Black Hole of Auschwitz. Polity Press, 2005.

Sherman, Hilde. Zwischen Tag Und Dunkel. Mädchenjahre Im Ghetto, Ullstein, 1989, pp. 35–41.

Star of David badge belonging to Renia Perel. Vancouver Holocaust Education Centre, https://collections.vhec.org/Detail/objects/7574

Teitelbaum, Rebecca. Recipe book. 1944-1945. Vancouver Holocaust Education Centre, https://collections.vhec.org/Detail/objects/7024

United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. “Jewish Badge: During the Nazi Era.” Holocaust Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/jewish-badge-during-the-nazi-era. Accessed 08 May 2020.

United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. “Jewish Badge: Origins.” Holocaust Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/jewish-badge-origins. Accessed 08 May 2020.

Vasvari, Louise O. “En-gendering memory through Holocaust alimentary life writing.” CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture, vol. 17, no. 3, 2015, doi:10.7771/1481-4374.2721

Comments by Amanda Grey