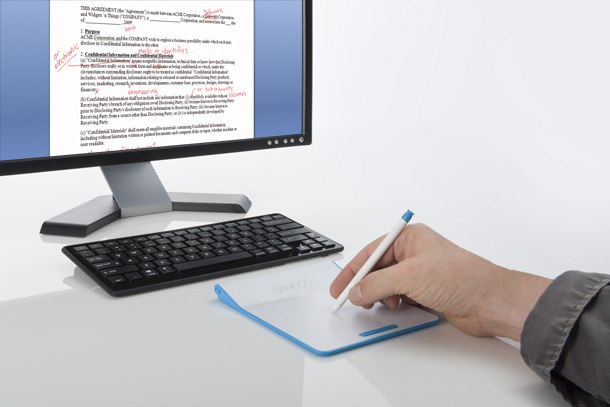

Before getting onto the reading, I will write a brief reflection on the multiliteracies and multimodality presentation last week. Despite the 10-minute delay as we discovered we could not reconnect an already-running presentation to the SMARTBoard, we accomplished our goal to demonstrate how the SB is an example of multimodality in the classroom. Well, most classrooms anyway. What surprised me in preparing the presentation, and even some of the in-class feedback during the presentation, was how much teachers and students don’t like using this expensive learning tool. Things could be done a lot more smoothly on a giant LCD television screen connected to a Bamboo electronic drawing pad, but without the hands-on-screen manipulation of objects and text, it just becomes another skill most teachers would tire of introducing to the class, especially as it will get replaced by tablets or the latest technological “fad”. Like it or not, SMARTBoard will be in the classrooms for a while, and with a growing number of children who have been using them since kindergarten (many of the primary students I meet in North Vancouver seem to know more about these devices than the teachers for whom I substitute). While it is a shame that high schools cut off these students from the technology they essentially grew up with, returning them to dusty used books and a mountain of photocopied handouts, there is also a push to make learning more asynchronous, at home on the students’ computers. Nevertheless, our LLED 558 presentation set out to rekindle creative use of classroom technology, and it will remain to be seen who will carry on the torch passed from us to them.

Now, onto this week’s readings, I would imagine if the grown-up versions of Chelsea and Lucas (from Edwards-Groves’ case study) were to present in our classroom, we would be in for a treat. At their young age, only a couple of years ago, they already have a handle on collaborative work in designing a presentation, as well as the imaginative showpersonship needed to impress net generation students. All three articles acknowledge that the look of learning has changed thanks to online resources, and as Gee would want to add in here, familiarity with gaming practices. It was amusing to read the back-and-forth between James Paul Gee and Julian Sefton-Green, one claiming that online games creates a community of practice, while the other questioning this approach of a gaming literacy that only promotes more gaming (Jewitt, 2008, p. 255). From some of the South Korean students I have tutored on the North Shore, university-aged older siblings could make a better career out of playing Starcraft than continuing with their studies. While JS-G scores a point on the side of caution (for teachers not to get too carried away by every digital bell and whistle), the children from Christine Joy Edwards-Groves’ (hereafter CJE-G) case study demonstrates, they like the wow factor being added to the research and planning they are required to do. It is especially a hit with the kindergarteners, and who knows what technology will be in use when they finish up their studies? A more balanced approach is presented in Jennifer Rowsell and Kate Pahl’s investigation of “sedimented identities” that demonstrates for each device in use in the classroom, students bring knowledge from home that may either support or contradict what needs to be done for school. Rowsell and Pahl place great emphasis on Bourdieu’s theory of “habitus” for defining their studies of the sedimentary layer of home world, school world and other influences on the students.

Although Bourdieu and habitus are two related terms that I have heard in the last couple of weeks, it is still a vague notion of what he means. The field theory video posted to the class makes it a bit more relatable. Reflecting upon Lisa and Meg’s presentation question about the Sri Lankan teacher’s habitus, the answer revealed itself from the discussion with Angela. When teaching a grade four classroom in the United States, there was a district-wide initiative to get students interested in getting into college, each teacher’s classroom was named after the college they had attended, and students took on the identity of that post-secondary (Angela’s college team was the Cougars, and so were her students). While there is not such a focus on the teacher’s university life in Canada, my experience as a Teacher on Call are walking into way too many classroom decked out with hockey posters and other paraphernalia, and the closer the hometeam gets to the play-offs, the more team jersey are spotted around the school. No wonder Vancouver had riots when the team lost the Stanley Cup (twice) when a student’s school world has become so hockey-ified.

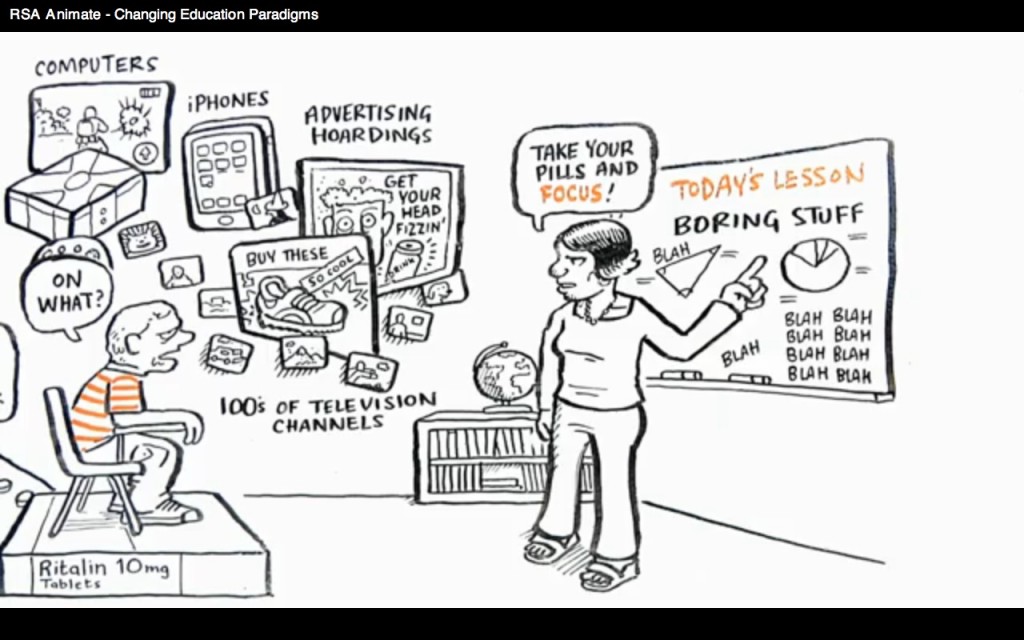

Lastly, looking ahead to multimodal text for next week, I would like to draw attention to the latest RSA Animate that came out last week: David Coplin’s Re-imagining Work:

Reference

Edwards-Groves, C. J. (2011). The multimodal writing process: changing practices in contemporary classrooms. Language and Education 25(1). 49-64.

Jewitt, C. (2008). Multimodality and literacies in school classrooms. Review of Research in Education 32. 241-267.