So much of what get referenced in this week’s article harkens back to a cultural crossroads for many North Americans: the 1990’s. Critical discourse theory, what can be seen as a beam of appropriately-named “white” light seemed to hit the prism of otherness, and separate into a full spectrum of multicultural, gendered and sociological categories. For Canada, a strong Liberal government for most of the decade created hope for social justice issues of race, national identity, gender equality and environmental policy had a fighting chance of becoming hegemony. Even the United States seemed to be going through a liberal phase, and attitudes were evident in the most familiar form (for Canadians): American network television. Reliable and wholesome prime-time shows like The Cosby Show and Cheers started to give way to edgier and slightly more cynical programs like The Simpsons and Friends, it was okay to explore controversial topics like same-sex marriage or to poke fun at the dysfunctional nuclear family. A far cry from the tumultuous counterculture movement of the 1960’s and early 1970’s, but this was a period in history where most of the radical ideas were accepted rather than resisted. Of course, this idealistic bubble seems to have burst at some point in September, 2001, when the whole world seemed to be dragged back a century or so into fear and war-mongering. Before then, there were some important issues to be resolved…

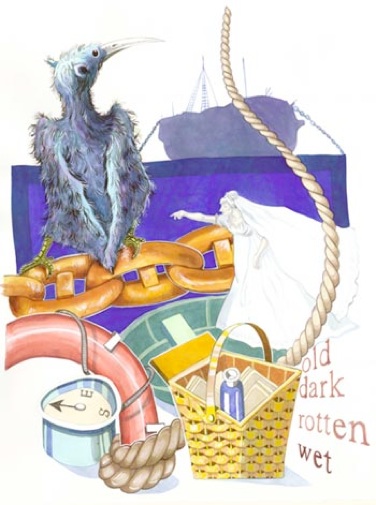

Lisa’s epiphany © 1995 by Matt Groening

More on her role model status at College Candy blog

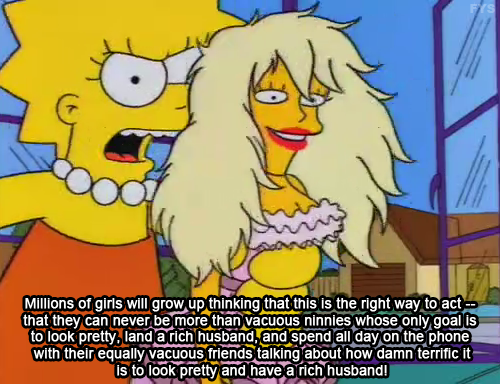

Feminist theorists like Annette Henry, bell hooks, and Trinh Minh-ha began to move beyond what Henry terms as the “whitestream” and view feminism though various perspectives. This paradigm shift is closely related to another issue that took hold around my family dinner table, vegetarianism. It started with my older sister, who lost her taste for meat in the mid-1980’s and made no attempt to hide her opposition to other family members enjoying favourite meals like roast pork, meatloaf or lamb chops. Shortly after her conversion to vegetarianism, my younger sister stopped eating meat as well. My parents became more accommodating with the food the provided the family, and as if they were ahead of the curve, restaurants seemed to be catering more and more to vegetarian diners. Yet it always remained a political stance with my older sister, and the rest of the family had to endure sighs and muttered slogan like “meat is murder” at the dinner table. By 1998, Ruth Ozeki’s book My Year of Meats was released and gave support to my crusading sister, making explicit the unwholesome process animals are raised to become food. It wasn’t until seeing it in print that the message really hit home (for me, it was many years later, and thanks to the organic industry many of my favourite meals are less toxic than they were). Feminist and post-colonial theories began to be taken up in academic institutions, and it really was an ironic matter of seeing the spectrum of difference through black and white of print.

My Year of Meats by Ruth Ozeki

My Year of Meats by Ruth Ozeki

My rating: 3 of 5 stars

Had to be read to believe the change it would make, and if it means eating a few less hamburgers or steaks for the rest of your life, consider yourself lucky. While no attempt was made to present her work as actual truth or reality, Ruth Ozeki states a clear case for authenticity through narrative arts.

View all my updates

One chapter in particular has the main character, Jane, returning to her small-town library in Quam, Minnesota, to find a social studies textbook she had checked out before as a teenager. The adult Jane works for a documentary television crew, and refers to herself as a documentarian along the same lines as Sei Shōnagon, the eleventh century author of The Pillow Book. What she finds at the library is Alexis Everett Frye’s Grammar School Geography with a shocking description of “The Races of Men” which Ozeki (1998) pulls quotes from:

Such natives are very ignorant. They know nothing of books; in fact, they know little, except how to catch and cook their food, build their rude huts, travel on foot through the forests, or in canoes or on rafts on the rivers, and make scanty clothing out of the skins of animals or fibers of grasses or bark. A few of them know how to raise grains in a crude way. Such people are savages. (p. 149)

Of course, no point in revealing which race Frye has determined is savage, as this piece of evidence can be added to the list of other racist and imperialist writers mentioned in article by Ngūgī wa Thiong’o. While reading Ozeki’s book this summmer, I was teaching a summer school course called Reading Across the High School Curriculum, and quoted this passage as evidence of how high school-entering students were taught their social studies more than a century ago. Fortunately, we could discuss these unfortunate references in relation to more politically correct (another product of the 1990’s) terms and phrases. I was also reading my class a novel, which had this amusing observation on another “Race of Men”:

Don’t get all sentimental, Hadridd. They’re dirty, spread diseases and breed endlessly. Did you know that a colony can outgrow the capacity of its environment in as little as twelve centuries? I know they look cute and can do tricks and make that funny squeaking noise when you stare at them close up, but honestly, culling is really for their own good. (Fforde, 2011, p. 198-9)

This part of a dialogue occurs in Jasper Fforde’s novel The Song of the Quarkbeast and is between two trolls discussing whether or not to kill one of the human characters they found in Trollvania, the northern half of the Un-united Kingdoms. They are not really distinguishing a particular race, simply the human race in general, but it is a telling commentary that this scene occurs somewhere in Scotland, and was written by a Welsh author (two distinct British cultures which were colonized by their English neighbour as if in rehearsal for the rest of the world). Wish I had read books like this one when I was getting into high school, back in the early ’90s.

Reference

Fforde, J. (2011). The song of the quarkbeast London: Hodder & Stoughton.

Ozeki, R. L. (1998). My year of meats. Hammersworth, Penguin.