The Path: ETEC 530 CoP Concept Map

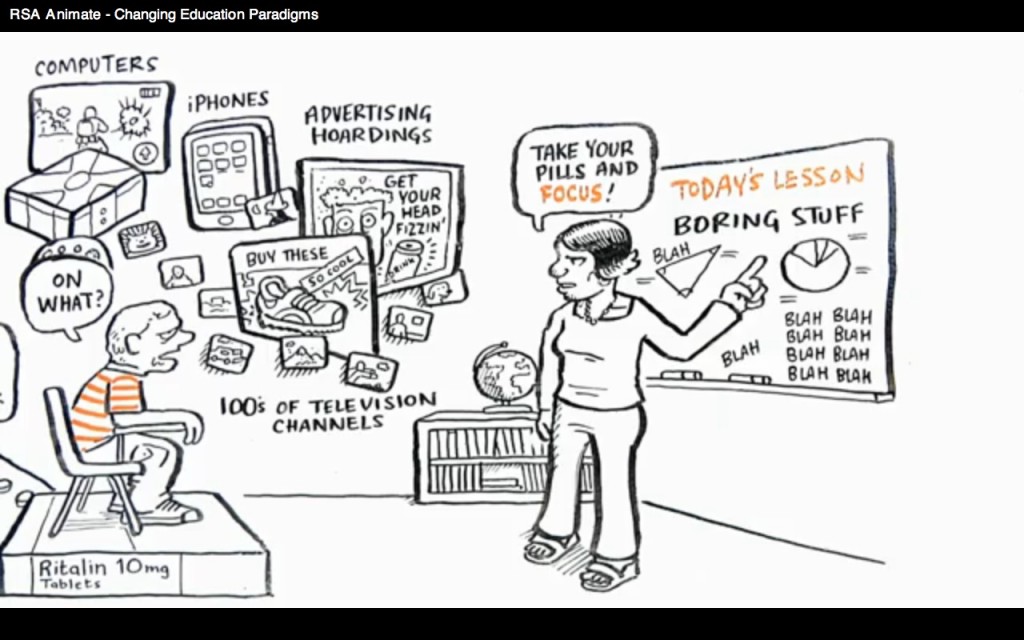

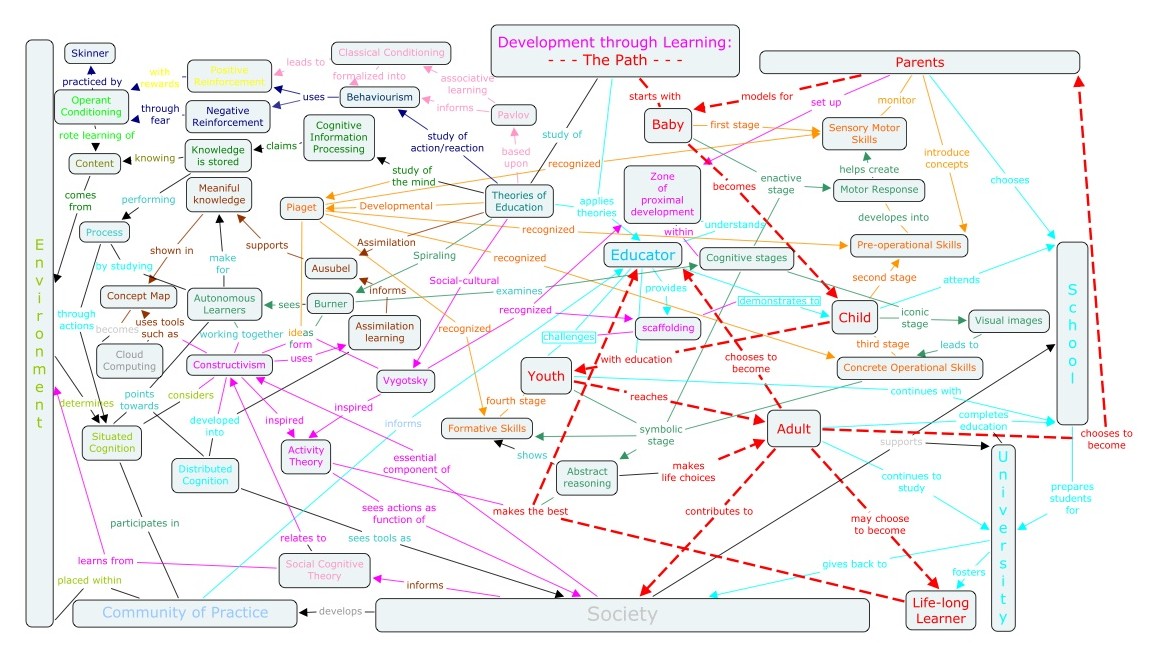

This week’s readings are circling back to my Master of Educational Techonology (MET) program recently completed “at” UBC… I know, I should have used the ampersat symbol to accentuate that most of my studied occurred on-line, but in my first year it was hard to know where to place the Community of Practice among on-line learners (some of them were studying in such exotic locations as Jamaica, Thailand and Turkey etc.), so hardly a community in the traditional sense. I believe both Wenger and Heath were some of the authors we looked at during the program, and the concept map was my first attempt to make it all make sense. And not-so surprisingly now, as I press on with my reading of Masny and Cole (2012) in preparation for my book review (Assignment 2), many of the same themes are coming together. The idea of mapping to show the connections between related ideas was also a big idea when I started my Bachelor of Education here at UBC. One of the instructors wrote about it in his textbook, Engaging Minds (Davis, Sumara & Luce-Kapler, 2008), and while students were not required to actually map anything in Brent Davis’ class, the introduction that I got from him led me continue on with the Education 2.0 studies in the MET program.

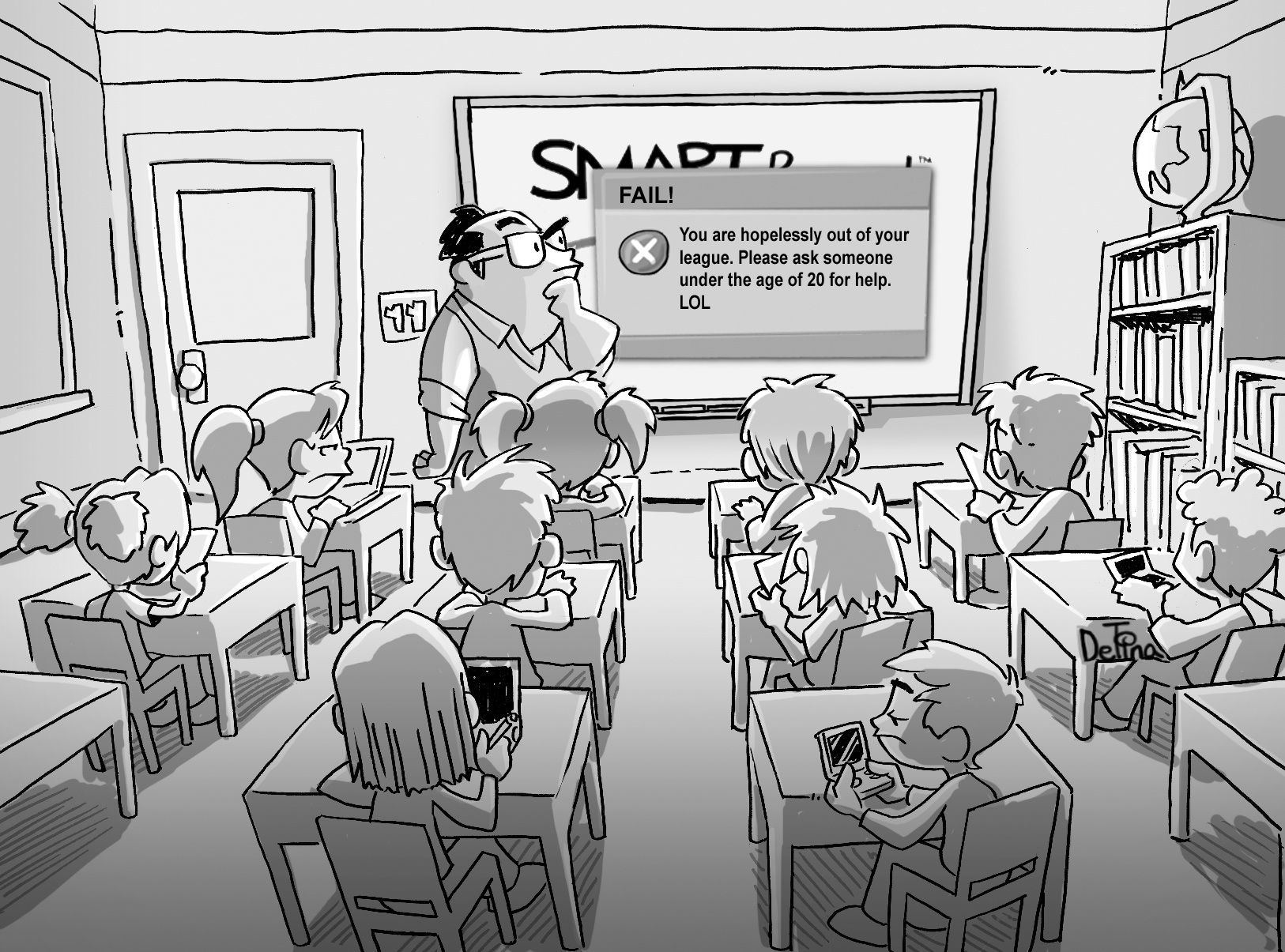

One of the most challenging courses in this program was ETEC 530: Constructivist Strategies for e-Learning, and while the readings were a lot to get through, what made this course especially difficult was the expectation to be constructivist while learning together. I should also hasten to add that it was the second term in the program, and perhaps I was still a bit green with on-line collaboration. My partners for the group presentation, however, were resistant to the asynchronous affordances (the techie way of saying we didn’t always have to be on-line at the same time to communicate) this course was trying to support. Rather than working with these teammates, I found myself racing around town (between teaching on call in North Vancouver and tutoring after-school at various homes) to find a free wifi area (usually Starbucks) to connect with the others. There were definitely a few missing components from this community, and more squabbling than social learning from my team members. It even got to the point where the instructor had to intervene, asking each of us to write out what we expected from the others. I am sure that file is saved somewhere, but from that point onward, my group projects became less social, more networked. The oddest thing about this whole ordeal in ETEC 530 was it ended up being my first A+ (95 over the class average of 92) in the MET program, so whatever my partners were claiming I wasn’t doing, my instructor at least thought otherwise!

Being a MET student living in Vancouver was not such an uncommon thing, as many of the other teachers in the program were from here or at least around the Lower Mainland. Every once in a while I would chat with other teachers and health care workers across the province and a few from other parts of Canada. It was a great introduction to the needs of teachers in rural and developing areas. Yet while there were some strange things done in the hinterland, not once did I encounter a teacher from any place resembling Trackton. Perhaps because even the enrolled teachers in the United States were more Mainstream-ish, leaving the former plantation land far behind. Anyone left in these communities, according to Heath, would either be working in the factory or preaching at the church. And yet, despite the numerous setbacks economic or otherwise, the children of Trackton develop a strong sense of self and literacy (perhaps self-literacy, if there is such a concept) because there is a community. The point I believe Heath makes is that children should not be placed in further difficult situations because the Mainstream standardized test scores, but a more thorough investigation of the circumstances the children are raised in is necessary.

When I first encountered Heath, my attitude was dismissive, and now I cannot claim being completely won over, at least there is a bit more understanding of her way and her words. And through the MET Program, which began shortly after Vancouver 2010 Olympic Games, I discovered that my hometown had begun its slow descent into Tracktoniness. There is no major industry left for Vancouver’s brightest, most engaged minds: the film industry is slowing down, video game and animation left for other parts of Canada, forestry, fisheries and mining (all damaging the earth) also in decline. It got to the point where the two things Vancouverites seemed to care passionately about were legalizing marijuana and rioting to get rid of a certain goalie. Most of the local teachers enrolled in the MET program got a bump in their salaries, with Teacher Qualification Services raising them from level 5 to level 6 (the highest a teacher in this province gets before moving into administrative positions). Would have been nice for me too, if I had a full-time teaching position. And don’t get me started on the plateauing of public school teacher salaries due to the budgetary schemes of oil-crazed politicians (both provincial and federal). The light at the end of the tunnel, through the MET program at least, was that it allowed me to get into the PhD program at UBC.

Lastly, Brian Street. After venting as much as I did about the lowered prospect of anyone who wants to build a career in Vancouver, there is hardly enough spirit left to discuss the academic hit-job the anthropologist Street enacts. Page after page, he sets up one theorist after another only to knock down Olson, Hildyard, Greenfield, Goody, Watt, Bloomfield, Lyons etc etc etc, while Street cunningly never (or at least not yet) offers any counterargument to his theory of literacy. The bottom of this blog page has a transcript of Street comment at the 2011 AERA conference in New Orleans, which are particularly revealing of his continued stand-offishness towards ideas that aren’t his. Enough said on that.

Reference

Davis, B., Sumara, D. and Luce-Kapler, R. (2008). Engaging minds: Changing teaching in complex times. 2nd Ed. New York: Routledge.

Masny, D. and Cole, D. R. (2012). Mapping multiple literacies: An introduction to Deleuzian literacy studies. New York: Continuum.