Here it is, just in the nick of time: LLED 601 Final Paper

-

Recent Posts

Recent Comments

- Leonore on LLED 536 Week 5

- DP on LLED 565D – Week 8

- KM on LLED 565D – Week 8

- YN on LLED 565D – Week 8

- MA on LLED 565D – Week 8

Archives

Here it is, just in the nick of time: LLED 601 Final Paper

A metrolingual Japanese language: texting speak

This may be as far as blogging goes for this term and I am really excited that most of this week’s reading have brought me back to a fun, familiar place: Japan!! It feels like ages since I was there, but actually was less than a year ago, so much of this county’s culture has had after an influence on design and structure of my learning as a teacher, especially from an educational technology point of view. And now the language itself gets attention from renown sociolinguists. In its written form, Japanese has several formats that share some phonetic similarities, but are metaphorically worlds away from each other: hiragana (the traditional “female” syllabary), katakana (“male” syllabary used mostly for imported words), Kanji (Chinese characters) and Romanji (Roman alphabet characters), and the most entertaining written language Emoji (short for emoticon or smiley characters). Hard to believe for people struggling with the finer points of their home language, especially with the fuss being made over “selfie” being included in the Oxford English Dictionary, that most people in Japan are fluent in all five written forms. Gunther Kress, Louise Rosenblatt and Michel Foucault would all have a field day trying to explain the meaning-making processes occurring in this country (turns out that Foucault had quite a few wild nights out whenever he was there). Even without the reference to Alastair Pennycook’s theories, the development of this fifth writing system is very metro and very fitting for a country that some have called the Galapagos Islands of mobile technology. My junior high school students, many of whom have made their way to university by now, were highly receptive to these unique forms of communication, and yet struggled with English, mostly because it is a visually unappealing language. And this is despite the earnest effort of tens of thousands uncertified English teachers (like me) who “invade” the country and attempt to make English fun by continually playing vocabulary bingo games with their students. When I started out, I inherited from my predecessor a desk crammed with endless photocopied sheets of such bingo activities as below, and promptly recycled them all so that I could have useful teaching material for my classes.

Isn’t this a game for senior citizens?

Without giving too much away, my research project for this class will look at children’s access to virtual world via mobile phones, and a new national policy to ban mobiles from schools. In the wake of Canada’s recent legislation to curb cyberbullying by making it illegal to post someone else’s intimate image without one’s permission (isn’t that what Facebook and Instagram are all about?), Japan seems to be going down the same reactionary route. It was refreshing to read, and then hear from (via Skype) Ryuko Kubota as she identifies the neoliberal collusion as the cause of so much English testing in Japan, and the businesses that do well designing and selling back the idea that English is everything Japanese people need. Many of the people I met in Japan seem to have bought into the “big lie” that English is good for your career. Interestingly enough, quite a few Japanese English teachers (usually called Japanese teachers of English so as not to confuse us JET programme participants), had originally studied the language in order to become flight attendants and pilots, and teaching English was their fall-back job. Not sure what this says about the language demands for those wishing to enter the aviation field, as compared to the less demanding task of inspiring others to learn the language. There is definitely an interesting case study in the making to look into these secondary career choices, and if it means sending LLED grad students to Japan for a couple of terms to conduct research, I will happily accept this assignment – must mention this to Dr Kubota when she returns…

My wife has lots of exciting stories to tell about building her English language skills, and the places that it allowed her to go. It is significant that most of her English language learning happened outside of Japan, and her story is very similar to the code-switching ones reported in Harissi, Otsuji and Pennycook. While these examples are grounded in everyday experiences, they still beg the question “so what” and I suppose a close reading of these articles will reveal more about the identities people form through language. And speaking of identities, it was easy to agree with most of Pennycook’s call to arms for critical analysis, but reading him suggesting to others to be humble and then he quotes himself exclusively on the first page of his 2010 article seems at odds with what he proposes. Also, is he the man that gave the world “plurilingualism” which will no doubt lead to a plethora of pluri- discourses, and I am not quite done with the multi- ones just yet! And even with all these theories and theoretical frames to choose from, they all seem to be parts that an actor could play, if the someone needed to demonstrate what being a thoughtful academic.

Performativity: “We are not as we are because of some inner being but because of what we do. We do not write our own scripts, although neither are our lives fully prescripted.” (Harissi, Otsuji & Pennycook, p. 527)

One chilling response for this otherwise uplifting quote comes from Jan Blommaert’s case study of Joseph’s ordeal in England, with the Home Office seeming to rewrite his lived history to make it fit with national linguistic norms. While my fascination with Japan and English learners from there, it is a vastly different story in many of the African countries where English is a second langauge, even taking a backseat place to other colonial languages like French or Dutch. And for the historical centre of the English speaking world, London, to decide where Joseph must live due to their interpretation of of his life-script, is enough to make one wonder if “what we do” is open to a Rashomon-like retelling.

Reference

Harissi, M., Otsuji, E. & Pennycook, A. (2012). The performative fixing and unfixing of identities. Applied Linguistics 33(5). 524-543.

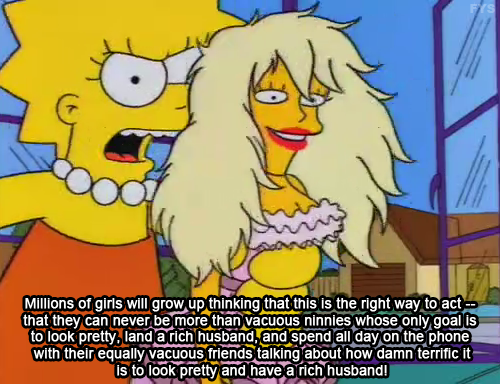

So much of what get referenced in this week’s article harkens back to a cultural crossroads for many North Americans: the 1990’s. Critical discourse theory, what can be seen as a beam of appropriately-named “white” light seemed to hit the prism of otherness, and separate into a full spectrum of multicultural, gendered and sociological categories. For Canada, a strong Liberal government for most of the decade created hope for social justice issues of race, national identity, gender equality and environmental policy had a fighting chance of becoming hegemony. Even the United States seemed to be going through a liberal phase, and attitudes were evident in the most familiar form (for Canadians): American network television. Reliable and wholesome prime-time shows like The Cosby Show and Cheers started to give way to edgier and slightly more cynical programs like The Simpsons and Friends, it was okay to explore controversial topics like same-sex marriage or to poke fun at the dysfunctional nuclear family. A far cry from the tumultuous counterculture movement of the 1960’s and early 1970’s, but this was a period in history where most of the radical ideas were accepted rather than resisted. Of course, this idealistic bubble seems to have burst at some point in September, 2001, when the whole world seemed to be dragged back a century or so into fear and war-mongering. Before then, there were some important issues to be resolved…

Lisa’s epiphany © 1995 by Matt Groening

More on her role model status at College Candy blog

Feminist theorists like Annette Henry, bell hooks, and Trinh Minh-ha began to move beyond what Henry terms as the “whitestream” and view feminism though various perspectives. This paradigm shift is closely related to another issue that took hold around my family dinner table, vegetarianism. It started with my older sister, who lost her taste for meat in the mid-1980’s and made no attempt to hide her opposition to other family members enjoying favourite meals like roast pork, meatloaf or lamb chops. Shortly after her conversion to vegetarianism, my younger sister stopped eating meat as well. My parents became more accommodating with the food the provided the family, and as if they were ahead of the curve, restaurants seemed to be catering more and more to vegetarian diners. Yet it always remained a political stance with my older sister, and the rest of the family had to endure sighs and muttered slogan like “meat is murder” at the dinner table. By 1998, Ruth Ozeki’s book My Year of Meats was released and gave support to my crusading sister, making explicit the unwholesome process animals are raised to become food. It wasn’t until seeing it in print that the message really hit home (for me, it was many years later, and thanks to the organic industry many of my favourite meals are less toxic than they were). Feminist and post-colonial theories began to be taken up in academic institutions, and it really was an ironic matter of seeing the spectrum of difference through black and white of print.

My Year of Meats by Ruth Ozeki

My Year of Meats by Ruth Ozeki

My rating: 3 of 5 stars

Had to be read to believe the change it would make, and if it means eating a few less hamburgers or steaks for the rest of your life, consider yourself lucky. While no attempt was made to present her work as actual truth or reality, Ruth Ozeki states a clear case for authenticity through narrative arts.

View all my updates

One chapter in particular has the main character, Jane, returning to her small-town library in Quam, Minnesota, to find a social studies textbook she had checked out before as a teenager. The adult Jane works for a documentary television crew, and refers to herself as a documentarian along the same lines as Sei Shōnagon, the eleventh century author of The Pillow Book. What she finds at the library is Alexis Everett Frye’s Grammar School Geography with a shocking description of “The Races of Men” which Ozeki (1998) pulls quotes from:

Such natives are very ignorant. They know nothing of books; in fact, they know little, except how to catch and cook their food, build their rude huts, travel on foot through the forests, or in canoes or on rafts on the rivers, and make scanty clothing out of the skins of animals or fibers of grasses or bark. A few of them know how to raise grains in a crude way. Such people are savages. (p. 149)

Of course, no point in revealing which race Frye has determined is savage, as this piece of evidence can be added to the list of other racist and imperialist writers mentioned in article by Ngūgī wa Thiong’o. While reading Ozeki’s book this summmer, I was teaching a summer school course called Reading Across the High School Curriculum, and quoted this passage as evidence of how high school-entering students were taught their social studies more than a century ago. Fortunately, we could discuss these unfortunate references in relation to more politically correct (another product of the 1990’s) terms and phrases. I was also reading my class a novel, which had this amusing observation on another “Race of Men”:

Don’t get all sentimental, Hadridd. They’re dirty, spread diseases and breed endlessly. Did you know that a colony can outgrow the capacity of its environment in as little as twelve centuries? I know they look cute and can do tricks and make that funny squeaking noise when you stare at them close up, but honestly, culling is really for their own good. (Fforde, 2011, p. 198-9)

This part of a dialogue occurs in Jasper Fforde’s novel The Song of the Quarkbeast and is between two trolls discussing whether or not to kill one of the human characters they found in Trollvania, the northern half of the Un-united Kingdoms. They are not really distinguishing a particular race, simply the human race in general, but it is a telling commentary that this scene occurs somewhere in Scotland, and was written by a Welsh author (two distinct British cultures which were colonized by their English neighbour as if in rehearsal for the rest of the world). Wish I had read books like this one when I was getting into high school, back in the early ’90s.

Reference

Fforde, J. (2011). The song of the quarkbeast London: Hodder & Stoughton.

Ozeki, R. L. (1998). My year of meats. Hammersworth, Penguin.

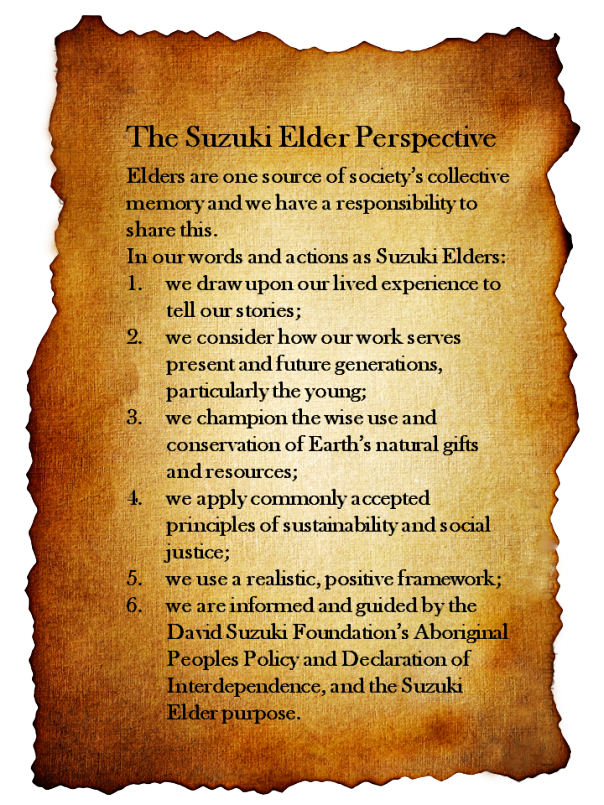

One of the most fascinating aspects of this week’s topic is that much of it deals with respectful and holistic connection to native land (in this case the place where someone is born) as well as Native land (belonging to Aboriginal ancestors who lived harmoniously with nature until Europeans messed thing up). So much of Archibald’s writing examines her connection to UBC and Vancouver, my native land, and I am compelled to include one of my favourite hometown heroes, David Suzuki, into this discussion. Around the same time as her book was being published, I began my studies at UBC, and I will have to look back through my notes to find moments in my Bachelor of Education program where Jo-ann Archibald presented her research to teacher candidates. She may have also been part of the lecture David Suzuki gave at UBC’s Longhouse, a few weeks before his Legacy lecture at the Chan Centre. It was an especially rare treat to see Suzuki in person, and hear how much he connects with First Nations culture. Someone, perhaps Archibald, presented Suzuki with a talking stick. Reading about its importance to Indigenous storywork empowers me to include a few more details about the pre-Legacy lecture I attended. Firstly, since his audience was mostly student teachers, his focus was on the importance of teaching. He made a comment about the Japanese word sensei, which has a fascinating connection to Elders of whom both Archibald and Suzuki discuss; there is also a punning Tricksterish side of Suzuki’s identity as sensei: the word sansei mean “third generation” which is also who Suzuki is: third-generation Japanese Canadian. Yet it is not so much his connection to Japan, or his family’s internment during the Second World War that identifies him now as his environmental activism, prompted by his connection to Native people and their relationship to the forests, rivers and especially coastlines.

From the Suzuki Elder’s WordPress site

The Suzuki Elder Perspective

The unfortunate history of Indigenous people in British Columbia, other parts of Canada and the United States is a difficult topic for many to understand fully. So much of the background of Archibald’s storywork methodology comes out of a murky, even haunted past of residential schools, punishing legislation and genocidal attempts to civilize the land and its people for Eurocentric purposes. Perhaps being an “outlier” and racially oppressed person in Canada gives Suzuki an empathetic understanding of how much is at stake the more that government and corporate interests place the economy over land and all things living on it. The subtitle of his 2009 Legacy lecture is “An Elder’s Vision for Our Sustainable Future” and aligns his interests found in Archibald’s Indigenous Storywork. The respect and patience both have for Elders’ knowledge and guidance from a more spiritual place (something that may seem at odds with Suzuki background in the field of science). One final mention of recall to the Legacy lecture with McCarty’s article, particularly when she describes how Navajo language became operationalized during the Second World War, similar to Suzuki’s claim in the documentary film of the Legacy lecture, Force of Nature: A David Suzuki Movie that one contribution to the pool of science (in this case anthropolgy/linguistics) raises the water level, and floats all boats, whether they be used for military purposes or for peace.

One more thing, I have attached my outline for this course’s final project: LLED 601 Research Paper Outline

Mapping Multiple Literacies: An Introduction to Deleuzian Literacy Studies by Diana Masny

Mapping Multiple Literacies: An Introduction to Deleuzian Literacy Studies by Diana Masny

Here is a brief glimpse at the review mentioned in my Goodreads post, that will soon be published in the Canadian Journal of Education: CJE Book Review Masny and Cole

Like Vygotsky would say, had he lived until the the mid 1990’s, I am entirely in the zone with this week’s readings on multiliteracies. It is hard not to view other theorists (especially the earnest NLSers) as a bit behind the curve. Yet as much as New London Group, Coiro, Knobel, Lankshear and Leu seem to be applying an operational theoretical framework, there are plenty of unanswered questions. The biggest one for me, which might have to leave until next term, is what have the digital literacies people been doing to differentiate from multiliteracies? I expected to find an answer to who they are in Geneviève Brisson’s proposal, but instead found a timely recapitulation of multiliteracies’ development up to a certain point. Brisson hits all the right “multi” buttons with her proposed research, yet there is also a slight disconnect between her framework and the case study itself, as most of the theorists mentioned in the former section do not entire reappear in the latter. In their introduction to Deleuzian literacy study, Masny and Cole (2012) present similar findings in their second chapter, pointing to the transcendental empiricism where virtual experiences in literacy are not tied to any one particular representation, as “[r]epresentation limits experience to the world as we know it – not to as a world that could be.” (p. 27) Perhaps Brisson picks up on the transcendental-ness by exploring what her case study students are becoming, rather than fitting into the model provided by a plethora of multiliterate scholars.

Determining who the multiliterates are becomes a Herculean task, not impossible (especially as they frequently cite their own individual work throughout A Pedagogy of Multiliteracies) but nevertheless daunting to figure out who said what. The strongest voice for me, merely as I more familiar with his writing than most of the others, is James Paul Gee. It is understandable that his earlier work with in critical discourse analysis and NLS needs to be understood fully to appreciate where he comes from, yet I have always pictured him as more concerned with where literacy is going. I suspect there will be a lot more of him when I take Prof. Asselin’s Digital Literacy course next term. It is Gee’s voice, seconded by Gunther Kress, that worked out the design parts of New London Group’s Pedagogy and I am sure once I get a copy of Coiro et al.‘s Handbook (would make a nice Christmas gift, in case family or friends are searching this blog for hints!) they will have more to say about which voice says what. In any case, Gee and Kress have lots to say about how things are designed, as well as the redesign of what technology is available, or as Kress often mentions “to hand”. Taking video games as the obvious lead in to design, recent developments with mobile games (Angry Birds being one of the prime examples), gamers no longer need to read instruction booklets but learn as they play, sometimes with in-game tutorials or often with the option to replay the level once completed. Nearly every video game emphasizes the just-in-time learning, where the skilled needed to defeat the level boss get introduced throughout the same level, allowing the player to hone their skills before facing off with the end of level challenge, the test if you will. The redesign, however, is the most interesting feature of multiliteracies pedagogy as skilled “readers” are able to switch modes to make more personal meaning. Remixing is something that has been around for ages, but has experienced a boost in activity thanks to the availability of digital video, on-line file sharing (YouTube and other websites) and a receptive audience (Facebook’s Like button seems to be the new standard of assessment). It always impresses me how much the New London Group got right back in 1996, at least with connections to what would be possible in the year 2000 and beyond, for the available technology at least.

What most teachers struggle with is the pedagogical predictions of the New London Group, how much the classroom is changing due to the invasiveness of the Internet, therefore Julie Coiro and Donald Leu teamed up with Michele Knobel and Colin Lankshear to produce the Handbook of Research on New Literacies well into the first decade of the 2000’s. Their purpose seems to be to make multiliteracies operational for classroom teachers while also raising awareness of literacy’s newness (and multiplicity). Their prediction of nearly half the world’s population being on-line by the year 2012 fell a bit short with the latest census (dated July 30th, 2012) holding at 34.3% of the world having access to the Internet. The graph below shows the two most highly populated countries, Asia and Africa, are below the world average which can be argued from a statistician or even an economist’s point of view, but I would put forth that educators around the world may be partially responsible. For every BCTF conference or workshop I have been at (I work as a facilitator for such Teaching Teacher On Call (TTOC) workshops as “Reality 101: A day in the life of a TTOC” or “Classroom management”), there is always one or two teachers who insist that children have way too much screen time, and the best place for a student’s smartphone is in the locker, or not purchased from the store in the first place. While I admit there is a tendency for students to get off-task with games and other distractions on the web, it is something the teachers will have to push through, hopefully in a constructive way. It would make for a nice Boxing Day if I could start reading up on Gee’s response to Facer, Joiner, Stanton, Reid, Hull, & Kirk 2004 case study of the mobile game “Savannah”. Perhaps after the nine-hour marathon screening of The Hobbit: An Unexpected Journey Extended Version. The research project I had intended to write for this class would have been on mobile learning through virtual world games, but as this is a case study I am conducting in LLED 558 and more details will emerge from the research rather than frontloading the methodology with expectations based on the framework – as Brisson herself keeps the questions open until she has a better understanding of what is going on with her students under observation. Look forward to connecting to my LLED 558 final assignment when more of it is written.

Downloaded from Internet World Stats

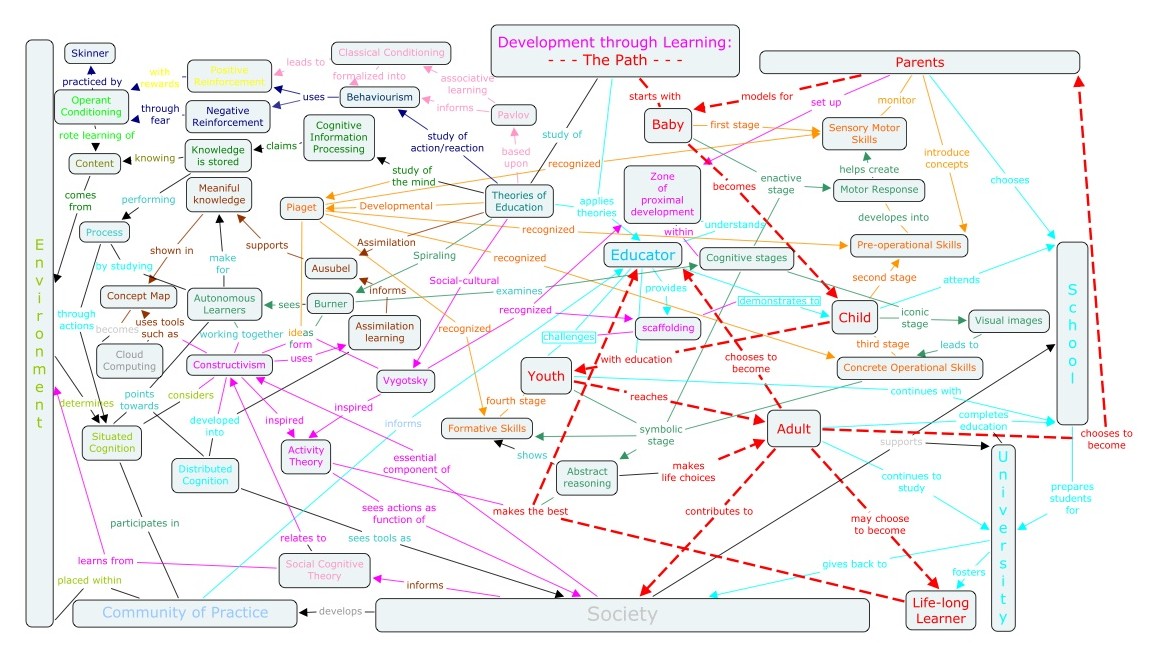

The Path: ETEC 530 CoP Concept Map

This week’s readings are circling back to my Master of Educational Techonology (MET) program recently completed “at” UBC… I know, I should have used the ampersat symbol to accentuate that most of my studied occurred on-line, but in my first year it was hard to know where to place the Community of Practice among on-line learners (some of them were studying in such exotic locations as Jamaica, Thailand and Turkey etc.), so hardly a community in the traditional sense. I believe both Wenger and Heath were some of the authors we looked at during the program, and the concept map was my first attempt to make it all make sense. And not-so surprisingly now, as I press on with my reading of Masny and Cole (2012) in preparation for my book review (Assignment 2), many of the same themes are coming together. The idea of mapping to show the connections between related ideas was also a big idea when I started my Bachelor of Education here at UBC. One of the instructors wrote about it in his textbook, Engaging Minds (Davis, Sumara & Luce-Kapler, 2008), and while students were not required to actually map anything in Brent Davis’ class, the introduction that I got from him led me continue on with the Education 2.0 studies in the MET program.

One of the most challenging courses in this program was ETEC 530: Constructivist Strategies for e-Learning, and while the readings were a lot to get through, what made this course especially difficult was the expectation to be constructivist while learning together. I should also hasten to add that it was the second term in the program, and perhaps I was still a bit green with on-line collaboration. My partners for the group presentation, however, were resistant to the asynchronous affordances (the techie way of saying we didn’t always have to be on-line at the same time to communicate) this course was trying to support. Rather than working with these teammates, I found myself racing around town (between teaching on call in North Vancouver and tutoring after-school at various homes) to find a free wifi area (usually Starbucks) to connect with the others. There were definitely a few missing components from this community, and more squabbling than social learning from my team members. It even got to the point where the instructor had to intervene, asking each of us to write out what we expected from the others. I am sure that file is saved somewhere, but from that point onward, my group projects became less social, more networked. The oddest thing about this whole ordeal in ETEC 530 was it ended up being my first A+ (95 over the class average of 92) in the MET program, so whatever my partners were claiming I wasn’t doing, my instructor at least thought otherwise!

Being a MET student living in Vancouver was not such an uncommon thing, as many of the other teachers in the program were from here or at least around the Lower Mainland. Every once in a while I would chat with other teachers and health care workers across the province and a few from other parts of Canada. It was a great introduction to the needs of teachers in rural and developing areas. Yet while there were some strange things done in the hinterland, not once did I encounter a teacher from any place resembling Trackton. Perhaps because even the enrolled teachers in the United States were more Mainstream-ish, leaving the former plantation land far behind. Anyone left in these communities, according to Heath, would either be working in the factory or preaching at the church. And yet, despite the numerous setbacks economic or otherwise, the children of Trackton develop a strong sense of self and literacy (perhaps self-literacy, if there is such a concept) because there is a community. The point I believe Heath makes is that children should not be placed in further difficult situations because the Mainstream standardized test scores, but a more thorough investigation of the circumstances the children are raised in is necessary.

When I first encountered Heath, my attitude was dismissive, and now I cannot claim being completely won over, at least there is a bit more understanding of her way and her words. And through the MET Program, which began shortly after Vancouver 2010 Olympic Games, I discovered that my hometown had begun its slow descent into Tracktoniness. There is no major industry left for Vancouver’s brightest, most engaged minds: the film industry is slowing down, video game and animation left for other parts of Canada, forestry, fisheries and mining (all damaging the earth) also in decline. It got to the point where the two things Vancouverites seemed to care passionately about were legalizing marijuana and rioting to get rid of a certain goalie. Most of the local teachers enrolled in the MET program got a bump in their salaries, with Teacher Qualification Services raising them from level 5 to level 6 (the highest a teacher in this province gets before moving into administrative positions). Would have been nice for me too, if I had a full-time teaching position. And don’t get me started on the plateauing of public school teacher salaries due to the budgetary schemes of oil-crazed politicians (both provincial and federal). The light at the end of the tunnel, through the MET program at least, was that it allowed me to get into the PhD program at UBC.

Lastly, Brian Street. After venting as much as I did about the lowered prospect of anyone who wants to build a career in Vancouver, there is hardly enough spirit left to discuss the academic hit-job the anthropologist Street enacts. Page after page, he sets up one theorist after another only to knock down Olson, Hildyard, Greenfield, Goody, Watt, Bloomfield, Lyons etc etc etc, while Street cunningly never (or at least not yet) offers any counterargument to his theory of literacy. The bottom of this blog page has a transcript of Street comment at the 2011 AERA conference in New Orleans, which are particularly revealing of his continued stand-offishness towards ideas that aren’t his. Enough said on that.

Reference

Davis, B., Sumara, D. and Luce-Kapler, R. (2008). Engaging minds: Changing teaching in complex times. 2nd Ed. New York: Routledge.

Masny, D. and Cole, D. R. (2012). Mapping multiple literacies: An introduction to Deleuzian literacy studies. New York: Continuum.

Each time I get a discourse of critical pedagogy in my hands, literally holding onto a book instead of an article or chapter reproduced on-line, I go to the index and see what names appear in the text. Listings of Gee, Vygotsky, Freire and Murray are good signs that parts of the book will be on somewhat familiar grounds, and every once in a while there are pleasant surprises, like a reference to Shakespeare or the Brontëe sisters will appear (very fortuitous that Dorothy Holland et al. has an entire section on Bakhtin and Vygotsky plus a brief allusion to Shakespeare!). One name I have noticed with increasing frequency is Sigmund Freud, and I can understand the connection between the present texts being read and the founder of modern psychoanalysis. Another name I would expect, yet rarely ever find, is the more radical former colleague of Freud, Carl Jung. This week’s readings put me in mind of this “other” psychologist and the brief outline of his beliefs I had read earlier this year. Understandably a controversial figure not to every scholar’s tastes, still some of the concepts he presents are a wealth of ideas to make connections with identity and culture. This is particularly true in connection to Gee’s interview describing how he got into critical discourse analysis (NB: all lower-case letters). Both Jung and Gee seem to be aware of the shifting positions one will have throughout one’s career, and even the occasional moments of synchronicity that leads to the Big Idea.

Jung: A Very Short Introduction by Anthony Stevens

My rating: 4 of 5 stars

A just-right introduction to this series by Oxford University Press, although I was tempted to see if Greer’s VSI on Shakespeare would have anything new to say on an already familiar topic. Stevens’ Jung was fascinating, especially as his psychoanalysis is just one of the many brilliant insights into what seems like a vastly complex and some would say indecipherable mind like Jung’s. Not only will readers have a better sense of who they are, and what archetypal influences shape them into individualized Selfs, but we get peeks at the course Jung’s life took, narrated adequately in his own words based on his self-analysis. It will be hard now to get through any of Freud’s groundbreaking works, such as the Interpretation of Dreams without thinking of his eventual breaking off with Jung, as if Freud was only prepared to go so far. Jung seems to have no limits, especially when it come to making sense of a theories as dynamic and multidimensional as the collective unconscious, shadow and mythological influences. As Stevens mentions numerous times, Jung was never one to be tied to one theory, and throughout his long career, everything he thought and wrote would be open to re-evaluation. It is obvious the best way into understanding him more is to read his ideas, and Memories, Dreams, Reflections has sat in my bookcase unread for far too long, yet in a synchronistic way I hope to discover more about my own self more than Jung with reading his biography. I’m even tempted to visit a therapist to see how it all will work out, and I am pleased to learn that his patients were given the freedom to find their Self by their selves. View all my updates

Like Jung, in some ways, Gee discusses at great length how he cobbled together his theories, almost as if he makes up his critical discourse analysis as he goes along. It may be a surprise to some classmates that he does acknowledge Mikhail Bakhtin twice in his interview, but not so much as the intellectual debt he owes the Russian literary theorist, rather how others should not be so beholden to the big ideas from the past. Instead, we get Gee’s surfing metaphor, making his discourse current for the Internet (and surfing) communities of practice: each scholar has to develop a sense of which wave to ride: join the established ones from the recent past like Kress and Fairclough and ride along, or wait for the next wave as Gee seems to be doing with video game literacy, or make some waves of one’s own. At some point in Jung’s career, he began to doubt most of what he had written before (perhaps fell prey to waves of criticism from the traditional Freudian analysis/surfers) and through this crisis produced even more astounding writing on alchemy, flying saucers and answers to questions raised by the Book of Job. Perhaps not as extreme as Jung (perhaps not yet in any case) Gee seems to be turning his back on the once-revolutionary multimodality theory of literacy, and can be seen by some as obsessing over video games. Yet he defends this choice by recalling how Sarah Michaels and Courtney Cazden’s critical analysis of sharing time radically changed the way educational researchers thought about this seemingly innocent primary grade ritual. Especially important topics as serious gamers are already making inroads towards academia. One last surfing analogy: in 2001 there was a documentary called Dogtown and the Z-Boys which showed the inception of skateboarding culture from the surfing community in Santa Monica. The Zephir team (Z-Boys) seemed just as surprised as anyone else that millions of dollars could be made from doing what most people saw as an idle pastime. Already in South Korea, there is a huge industry created around playing the on-line game StarCraft and perhaps a student’s Minecraft skills will be more in demand than an ability to spot names like Jung, Brontëe or Shakespeare in book indices.

Speaking of the index, what exactly is “indexicality” as mentioned in Davies and Harré’s article? Most of the way through this article, I found myself a bit too much in the deep end of discursive analysis, and this notion took me aback. Admittedly, there were moments of crystallization, particularly their example from Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina, reminding me of Jasper Fforde’s footnoter conversation on the same novel that appears (at the bottom of various pages) throughout The Well of Lost Plots. Anyhow, where was I? Near the end of their discussion on identity-makers, they examine Robert Munch’s Paper Bag Princess, very much an anti-Anna Karenina heroine, from a feminist perspective. Must have been disheartening for the researchers when the students reacted negatively to the active heroine, mostly those who see the poorly-dressed princess as “bad”. Seems particularly cruel as the story itself is designed to assert the heroine’s side of the story and change the hegemonic view that girls must patiently wait for the boys to restore order to the kingdom. I wasn’t a huge Munch fan when I was growing up (a bit before my time, actually) and while I can look back at the radical changes he set for the Once-upon-a-time crowd, at the time I only remember being peeved that boys were portrayed as dumb bullies. Now I am quite fond of children’s literature that pushes the boundaries and problematizes the hero’s journey – most of Fforde’s novels have women in the narrative driver’s seat. And to bring the discussion back to Jung, he opened the door not only for Joseph Campbell’s Hero with a Thousand Faces by working out his own archetypal images, but Jung also has interesting theories about dual masculine/feminine identies (animus and anima) that I need to explore further to see how they apply to literacy.

This brings me back to Dorothy Holland, and the first two chapters of Identity and Agency in Cultural Worlds. While Jung does not appear anywhere in this book, a shadow of anima theory seems to be lurking in chapter one with its evocative title “The Woman Who Climbed up the House” – both Campbell and Munch would have written something relating to Holland and Debra Skinner’s Nepalese field work. The pseudonymous Gyanumaya could not enter the rented house to be interviewed by Holland and Skinner, and her creative solution inspires Holland to write about how some people are positioned in society, and others resist the constraints placed by this positioning. At some point, it may have occurred to Gyanumaya that not being able to enter the house could have simply sent her home, her story never shared with the foreign researchers. It is not here, however, that we find out what she contributed to their study, other than the house-climbing incident; more details can be found, I assume in her 1992 New Directions in Psychological Anthropology article. She does, unlike Gee, have no problem directly referencing Bakhtin and Vygotsky, claiming to be standing on the shoulders of these socio-cultural giants – talk about being a head taller! I am very interest to read more of Holland et al. discourse, and may have some time during the December break to read their work while also starting in on Jung’s Memories, Dreams, Reflections.

Reference

Holland, D., Lachicotte, W. (Jr.), Skinner, D. and Cain, C. (1998). Identity and agency in cultured worlds. Cambridge: Harvard U P.

Holland, D. (1993). The woman who climbed up the house: Some limitations of schema theory. In Theodore Schwartz, Geoffrey White and Catherine Lutz (Eds.) New Directions in Psychological Anthropology. Cambridge: Cambridge U P. 68-81.

Here is the article from the Canadian Journal of Education: Ciampa 2012

Click on this link to download my article review: Article Review for Ciampa 2012

Please post comments on this blog if you’d like. Thank you.

Danger: Violence!

No time to mind the p’s and q’s with this music video, this week’s readings touch a nerve with a topic supposedly inappropriate for most students, yet as Bourdieu would point out, all within the “field” of child development: violence. It is as unavoidable as Bourdieu, Foucault and Marsh make it out to be in their writing. Evidence can be found in the earliest form of children’s literacy: my wife, an Early Child Care Educator, began a project with the 3-to-5 year old children at her centre. They would create a story, each taking turns with a sentence. From the outset, the children decided that they wanted to tell a happy story, and selected an animal living in the woods, going for a walk. It did not take too long to establish the field, and as soon as the animal came to some water, it fell in and was eaten by a shark. When my wife asked what happened to the happy story, the children had unanimously decided that this turn of events is the only one that could take place; the doxa determines that stories must end tragically, despite many examples in the centre of happy endings. On a similar train of thought, high school students that I tutor are often given open-ended drama activities where they get to create a new final chapter for Lord of the Flies or a different fifth act of A Midsummer Night’s Dream, and it seems like the only ending is one where the characters find a way to kill each other off. This is not to say that every single child is innately violent, especially those digital natives who are more familiar with video games and popular culture than paper-bound books. Perhaps there is something wrong with the schooling, the forcing of creative choices on students who just want to end the story in the quickest and most final way possible: the protagonist dies, the end!

Foucault speaks about this tendency toward violence in his abridged chapter “the Discourse of Language” and words like “prohibition”, “control” and “discipline” are used with increasing frequency. One can only imagine what words were used in the omitted passages (everywhere there was a “[…]” indicated parts of the lecture we are not privileged enough to hear). There are words one must not say, like yelling fire in a crowded theatre, and as much freedom as we are supposed to share in democratic societies, there is the implicit understanding of what sane people say and do. What mad people say can be ignored, what they do can be controlled through institutions like hospitals or prisons. “Every educational system is a political means of maintaining or of modifying the appropriation of discourse,” (Foucault, 1970, p. 239) and as teachers, it is really up to us to monitor what is happening for the future citizens. My wife, on the other hand, argues that children as young as the ones at her infant-toddler centre are already citizens, and the process of schooling withholds democratic participation, for their own benefit of course. Even for the student teacher Jackie Marsh interviews, there is a sense that the participants are being held back, their version of popular culture in their practica was rife with misunderstanding and possible falsehoods in reporting. As much control is needed at this end of the education system as it does at the beginning. While Marsh centres upon the limited field of experience of students’ popular culture for one or two of the participants, using Bourdieu’s theory as her frame, the suggested better way is to let students decide for themselves what is the best way to interact with literacy. Letting go of tried-and-true standards, like Golding and Shakespeare, may be the only way forward, as long as students are aware that some people at some point in history thought these authors were as exciting as Pokëmon or Minecraft.

Lastly, Bourdieu (1982), in his own words, sees that intimidation “can only be exerted on a person predisposed (in his habitus) to feel it” (p. 471) which sounds like a tough-love approach to moderating the psychological scars we inflict upon each other with our choices of words. Blaming the victim, or just simply pointing out that some people have the ability, thanks to various forms of capital, to absorb or ignore? As the majority of scholars seem to be increasingly French, I am reminded of a silly yet politically-charged moment in cultural history, not too long ago, when “freedom fries” were items to be found on American menus. Despite centuries of ideological sharing between France and the United States (the Statue of Liberty being an iconic symbol of the pact between the two nations), one political act of violence turned brother against frère. What would Bourdieu made of this Jimmy Fallon and Tina Fey’s Weekend Update?

Reference

Bourdieu, J. (1982). “The production and reproduction of legitimate language”. In Routledge Reader (reference needed). 467-477.