Here are the notes, a very rough draft for what I hope will be a much more polished off one-pager on this week in RMES. Will have to find out from Carl, my writing instructor, whether this creative-juice stirring counts towards my LLED 534 as well as for this course. Feels like I am double-dipping on the assignment, yet Carl may be okay with me trying to write as much and in as many different ways as I can.

Here is the final draft, sent off on Saturday night:

B.D. Sharma, “On Sustainability” in Michael Tobias and Georgianne Cowan, The Soul of Nature (New York: Continuum, 1994), pp. 271-8.

Can current sustainability problems be solved through more intelligent application of conventional modern ideas about humans, the natural world, and the relationship between them, or are fundamental changes to prevailing basic assumptions and attitudes required?

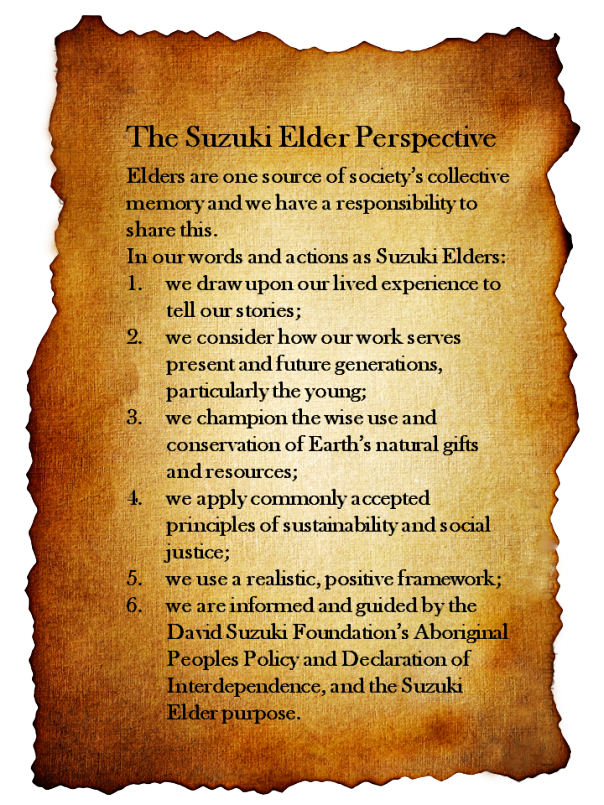

In his address to the “estate-managers” attending 1992 Rio Earth Summit, Sharma gets very close to defining one of the most important issues with human attempts towards sustainability: how the First World tends to view the Third and Fourth Worlds’ poverty as an issue that needs to be resolved for the sake of all worlds. Contrary to the basic assumption of trickle-down theory that wealth will solve all problems, described here as an economical framework, the First World has done more harm to others with an imposing colonial attitude of taking valuable resources from impoverished countries, yet leaving behind just enough to support their consumptive habits. For instance, tropical forests may be stripped bare by the estate-managers, replaced by faster-growing, non-indigenous trees like pine, and called carbon dioxide sinks for developed and developing countries. Small independent communities like Sharma’s Dhorkatta receive strict policies from their national government based upon a colonial attitude that continue to support the Western economic system, to the point where the only acceptable solution would be Dhorkatta to become a cosmopolitan city and accept modern consumerism that devalues human and non-human life for the sake of the economy. He offers “a more humane, sustainable and equitable” (p. 278) paradigm based upon Gandhi’s belief in village republics.

The challenge Sharma lays out is to think locally about how the environment must be sustained, giving an example of “the tree that fulfills all desires” that must have once provided shelter, food and perhaps medicine for his community. The relationship between human and the natural world, it could be argued, remains the same as the globalized destruction for the First World’s economic scheme, only on a smaller scale. Humans will take what they need from the environment, and once the resources are totally depleted, they move elsewhere. Sharma’s attempt to address his “friends” at an international conference on sustainability come across as either berating “you,” on the one hand, for allowing destructive practices to intensify to the point of threatening “our” way of life, or on the other hand, venting frustration at “they” who establish consumerist habits that appeal to you but not us. How would others have felt to leave their communities and travel to Brazil for the conference only to hear that their way of life conflicts disastrously with another community’s sustainability scheme? There may be the strong urge to do something about such oversights when they return to their homes: petition local governments not to import timber from the Madhya Pradesh or revolt against the economic framework that created a two-caste dualism of extreme poverty and wealth? One would hope that Sharma came to the conference in order to listen to people from other countries, perhaps learn whether or not they truly are friends or foes to the Dhorkattan ecosystem. A teenaged Severin Suzuki gave a speech on similar theme at the same conference, perhaps with B. D. Sharma on the same stage as her. As much as I would like to believe each speaker had a profound impact on the other, Suzuki’s “I” and Sharma’s “we” most likely still remain worlds apart.