One of the most fascinating aspects of this week’s topic is that much of it deals with respectful and holistic connection to native land (in this case the place where someone is born) as well as Native land (belonging to Aboriginal ancestors who lived harmoniously with nature until Europeans messed thing up). So much of Archibald’s writing examines her connection to UBC and Vancouver, my native land, and I am compelled to include one of my favourite hometown heroes, David Suzuki, into this discussion. Around the same time as her book was being published, I began my studies at UBC, and I will have to look back through my notes to find moments in my Bachelor of Education program where Jo-ann Archibald presented her research to teacher candidates. She may have also been part of the lecture David Suzuki gave at UBC’s Longhouse, a few weeks before his Legacy lecture at the Chan Centre. It was an especially rare treat to see Suzuki in person, and hear how much he connects with First Nations culture. Someone, perhaps Archibald, presented Suzuki with a talking stick. Reading about its importance to Indigenous storywork empowers me to include a few more details about the pre-Legacy lecture I attended. Firstly, since his audience was mostly student teachers, his focus was on the importance of teaching. He made a comment about the Japanese word sensei, which has a fascinating connection to Elders of whom both Archibald and Suzuki discuss; there is also a punning Tricksterish side of Suzuki’s identity as sensei: the word sansei mean “third generation” which is also who Suzuki is: third-generation Japanese Canadian. Yet it is not so much his connection to Japan, or his family’s internment during the Second World War that identifies him now as his environmental activism, prompted by his connection to Native people and their relationship to the forests, rivers and especially coastlines.

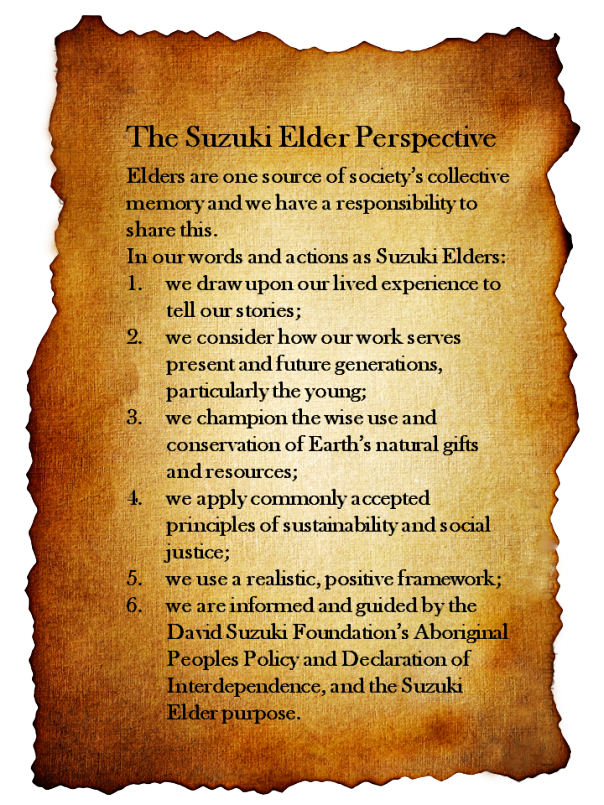

From the Suzuki Elder’s WordPress site

The Suzuki Elder Perspective

The unfortunate history of Indigenous people in British Columbia, other parts of Canada and the United States is a difficult topic for many to understand fully. So much of the background of Archibald’s storywork methodology comes out of a murky, even haunted past of residential schools, punishing legislation and genocidal attempts to civilize the land and its people for Eurocentric purposes. Perhaps being an “outlier” and racially oppressed person in Canada gives Suzuki an empathetic understanding of how much is at stake the more that government and corporate interests place the economy over land and all things living on it. The subtitle of his 2009 Legacy lecture is “An Elder’s Vision for Our Sustainable Future” and aligns his interests found in Archibald’s Indigenous Storywork. The respect and patience both have for Elders’ knowledge and guidance from a more spiritual place (something that may seem at odds with Suzuki background in the field of science). One final mention of recall to the Legacy lecture with McCarty’s article, particularly when she describes how Navajo language became operationalized during the Second World War, similar to Suzuki’s claim in the documentary film of the Legacy lecture, Force of Nature: A David Suzuki Movie that one contribution to the pool of science (in this case anthropolgy/linguistics) raises the water level, and floats all boats, whether they be used for military purposes or for peace.

One more thing, I have attached my outline for this course’s final project: LLED 601 Research Paper Outline