Karaoke versus Folk Singing

by normans ~ April 25th, 2013. Filed under: World Music Studies.The other morning I was walking down the main street of my neighbourhood, take-out coffee in hand, when I walked by my local karaoke store for the umpteenth time. I use the word “my” advisedly, because I’m not a karaoker. And I am not their target consumer, given that all the posters in the window where written in Chinese and Tagalog. The sight of the familiar little shop reminded me yet again of the huge interest in karaoke among East, Southeast and South Asians.

My walk-by this time was different however, because I suddenly began thinking about English traditional folk-singing.

Hootenannys and the musical cringe

During the mid-60s, folk music sat triumphantly on the top of the charts in North America and England. Although folk music’s popularity was fueled by the likes of Bob Dylan, it also democratized music-making by strongly advocating solo and group singing, no matter the skill level, from beginners to almost-professional.

There were two forms of participation at the local coffee shops and late-night folk clubs. People took turns at a microphone on the miniscule stage or, if they were intimidated by the bravery needed for solo performance, they could always join in the group sing-along featured in the choruses of each song. Today, most people understand the repeated chorus in a popular song form to be a representation of the theme of the song while the verses unfold the narrative. That is true, but it’s easy to forget that the word “chorus” also refers to a choir. No doubt both meanings are relevant, while the former definition has been long forgotten.

At the height of the impulse to sing out loud, a magazine called Sing Out was founded and their book with its circa one thousand lyrics, entitled Rise Up Singing, is still in print. Group singing can be seen in a television program called hootenanny, the term often used by folkies to describe the chorus sections. They were especially popular on university campuses. I have to admit that I cringe whenever I see archival footage of the episodes, as I did when hootenannies were big, but that tells you more about my generation than the culture of the event.

Vancouver had its folk-singing community and its folk clubs, in keeping with the times. Born-and-bred Vancouverites now in their 70s remember the Advanced Mattress Coffee House at 10th and Alma. The even more iconic Inquisition Coffee House was featured in the wonderful movie American Boyfriends (1989), the sequel to My American Cousin (1985). The stories of both movies take place in Penticton and Vancouver, and in AB, several scenes were shot in The Inquisition in Vancouver at 726 Seymour Street, complete with checkerboard table cloths and dripping candles set in empty, straw-wrapped bottles of Chianti.

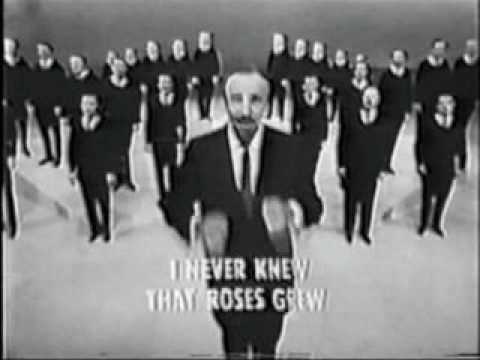

In a highly ill-thought-out response to the folk-music craze, and especially the phenomenon of the hootenanny, Columbia Records commissioned their top exec, Mitch Miller, to produce sing-along LPs under the general category called Mitch Miller and his Sing-Along Gang. His productions are some of the most exquisite forms of music kitsch known to mankind, right up there with Liberace, Lawrence Welk and Andre Rieu. The Silent Generation thought nothing of playing Mitch Miller’s LPs at their early 60s suburban barbeque parties. It is the likes of Mitch Miller that explains the birth of rock and roll. Picture an episode of Mad Men.

Social Isolation

The roots of folk music are found in the almost mythical stories about pre-industrial rural people and the urban working poor gathered together to sing lustily or longingly in pubs and kitchens , or at various massed hard labour where they needed to synchronize their combined physical efforts (e.g. , sea shanties). In addition, there is a mountain of proof of recreational singing in the form of thousands of printed ballads and song-sheets. One of the most eloquent descriptions of home-spun entertainment is found in Lark Rise to Candleford, by Flora Thompson where she describes life in rural England at the turn of the 19th century. Her depiction of a sing-around at the local pub is one of the most endearing and largely factual narratives in English bucolic literature. These musical soundscapes were pedestaled by the New Left of the 60s as evidence of the “humanity” embodied in “the people”, as opposed to mass consumerism fueled by mass advertising and driven by the capital of the elite ruling classes.

Since those halcyon times of 60s protest songs and folk ballads, group sing-arounds in folk music clubs have largely disappeared, save a few niche organisations with dwindling membership. Today, die-hard folkies lament the end of public singing, either in folk song clubs, kitchens and pubs. They point to the advent of digital PM3 players to explain the collapse of community music-making and even community building.

They aren’t alone. Sometime after the end of the popular folk music era and its hootenanny craze we find the development of personal listening devices, beginning with the Walkman. Although the convenience of PLDs is undeniable, the advent of personal music players and their ear bud attachments, now called headphone culture, has had a curious blowback. Sociologists around the world are expressing concerns for young people who seem to be retreating into themselves, rather than expanding outwards as they come to occupy the mainstream of public culture. This trend towards emotional solipsism is creating such an alarm that it has spawned an academic discourse, led by the pioneer Michael Bull and before him, Robert Putnam. Writing in 2000 Putnam expressed outrage and sadness at the precipitous decline in the number of people participating in social groups (such as bowling leagues, his first discovery), to the detriment of the very foundation of collective will – democracy. The solitary life-style of the MP3 listener has been a constantly recurrent theme in the ethnographies compiled by my students, year after year.

When I discuss the collapse of pre-industrial age home entertainment in favour of the solitary pleasure of listening to music on PLDs, I then take a round of votes to learn who uses the musical skills (mainly piano), the core of their bachelor of music studies, in a recreational setting, either in the form of singing or instrumental music (e.g., parlour piano). No hands are raised, confirming the fears yet again.

Then it occurred to me that I should ask a second question after the gloomy response of the first one. “Who does karaoke here?” Half the classroom shot up their hands, almost all of them East Asian. This was followed by lots of excited chatter, with students spilling over each other’s descriptions of how much fun it is to go out with friends and sing all night! The other half of the class stares in disbelief.

Sing-arounds from two worlds

Karaoke, a Japanese fad from the 60s, ultimately extends back in time through 50’s crooning, enka, to traditional folk song, minyo, where singing around the kitchen fire and in the agricultural fields was as endemic as it was in England. Last year I ventured into a Western Karaoke bar (actually a Legion) and discovered a lot of serious-minded (i.e. non-ironic) white singers having a great time apparently on a weekly basis. At about the same time, I discovered the Huey Lewis-Gwyneth Paltrow exploration of Western karaoke in the film Duets (2000).

So, what are the differences between a sing-around in a folksong club and a karaoke bar? Forgetting the surface for a moment (i.e., the radically different style of the songs) the differences on first glance appear to be centred on memorisation and performativity. Folk-song circles are notorious for requiring all singers to have their lyrics memorized. The concern seems to be replicating an “authentic” performance where pre-industrial singers supposedly never used (and perhaps couldn’t read) sheet music. The great English pioneer revivalist, Ewan MacColl, had a hand in this style when he developed his unwritten code of behaviour in his Ballad and Blues folk song club, the first folk music club in England (which abandoned American blues in favour of English ballads.) I have to admit my support for this position, having seen groups of singers (like modern-day choirs, actually) staring intently at their music books instead of each other during a sing-around. Karaoke is solidly built on the idea that singers, and even their audiences, have easy access to the lyrics because they’re broadcast on a television monitor, sometimes with the 21st century iteration of the bouncing ball pointing out the words at the moment of their place in the song. My impression is that some (many?) singers don’t even need to see the lyrics on the screen, but regardless, the convention removes the fear and listener barriers to understanding the words of the singer. Secondly, folk- singers in folk clubs today tend to take the stance of a serious even meditative story-teller, whereas karaokers are as effusive and flamboyant as their singing models. In other words, karaokers don’t appear to take themselves as seriously as folk-singers.

Conclusion

I want to see these two scenarios brought together. Then I’ll give it a shot.

Readings

Niall MacKinnon (1993) The British Folk Scene: Musical Performance and Social Identity

Michael Bull (2007) Sound Moves: iPod Culture and Urban Experience

Robert D. Putnam (2000) Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community

Roelof Hortulanus, Anja Machielse and Ludwien Meeuwesen, authors (2006) Social Isolation in Modern Society

Noah Arceneaux and Anandam Kavoori , editors (2012) The Mobile Media Reader

Flora Thompson (1939/1973) Lark Rise to Candleford

Rob Drew (2011) Karaoke Nights: An Ethnographic Rhapsody

Brian Raftery (2008) Don’t Stop Believin’: How Karaoke Conquered the World and Changed My Life