Every April, at the end of the “school year” at UBC, the Carl Wieman Science Education Initiative (CWSEI) holds a 1-day mini-conference to highlight the past years successes. This year, Acting-Director Sarah Gilbert did a great job organizing the event.  (Director CW, himself, is on leave to the White House.) It attracted a wide range of people, from UBC admin to department heads, interested and involved faculty, Science Teaching and Learning Fellows (STLFs) like myself and grad students interested in science education. The only people not there, I think, were the undergraduate students, themselves. Given that the event was held on the first day after exams finished and the beginning of 4 months of freedom, I’m not surprised at all there weren’t any undergrads. I know I wouldn’t have gone to something like this, back when I was an undergrad.

(Director CW, himself, is on leave to the White House.) It attracted a wide range of people, from UBC admin to department heads, interested and involved faculty, Science Teaching and Learning Fellows (STLFs) like myself and grad students interested in science education. The only people not there, I think, were the undergraduate students, themselves. Given that the event was held on the first day after exams finished and the beginning of 4 months of freedom, I’m not surprised at all there weren’t any undergrads. I know I wouldn’t have gone to something like this, back when I was an undergrad.

Part 1: Overview and Case Studies

The day started with an introduction and overview by Sarah, followed by 4 short “case studies” where 4 faculty members who are heavily involved in transforming their courses shared their stories.

Georg Rieger talked about how adding one more activity to his Physics 101 classes made a huge difference. He’s been using peer instruction with i>Clickers for a while and noticed poor student success on the summative questions he asked after explaining a new concept. He realized students don’t understand a concept just because he told them about it, no matter how eloquent or enthusiastic he was. So he tried something new — he replaced his description with worksheets that guided the students through the concept. It didn’t take a whole lot longer for the students to complete the worksheets compared to listening to him but they had much greater success on the summative clicker questions. The students, he concluded, learn the concepts much better when they engage and generate the knowledge themselves. Nice.

Susan Allen talked about the lessons she learned in a large, 3rd-year oceanography class and how she could apply them in a small, 4th-year class. Gary Bradfield showed us a whole bunch of student-learning data he and my colleague Malin Hansen have collected in an ecology class (Malin’s summer job is to figure out what it all means.) Finally, Mark MacLean described his approach to working with the dozen or so instructors teaching an introductory Math course, only 3 of whom had any prior teaching experience. His breakthrough was writing “fresh sheets” (he made the analogy to a chef’s specials of the week) for the instructors that outlined the coming week’s learning goals, instructional materials, tips for teaching that content, and resources (including all the applicable questions in the textbook.) The instructors give the students the same fresh sheet, minus the instructional tips. [Note: these presentations will appear on the CWSEI shortly and I’ll link to them.]

Part 2: Posters

All of my STLF colleagues and I were encouraged to hang a poster about a project we’d been working on. Some faculty and grad students who had stories to share about science education also put up posters.

My poster was a timeline for a particular class in the introductory #astro101 course I work on. The concept being covered was the switch from the Ptolemaic (Earth-centered) Solar System to the Copernican (Sun-centered) Solar System. The instructor presented the Ptolemaic model, described how it worked, asked the students for to make a prediction based on the model (a prediction that does not match the observations, hence the need to change models.) The students didn’t get it. But he forged onto the Copernican model, explained how it worked, asked them to make a prediction (which is consistent with the observations, now). They didn’t get that either. About a minute after the class ended, the instructor looked at me and said, “Well that didn’t work, did it?” I suggested we take a Muligan, a CTRL-ALT-DEL, and do it again the next class. Only different this time. That was Monday. On Tuesday, we recreated the content switching from an instructor-centered lecture to a student-centered sequence of clicker questions and worksheets. On Wednesday, we ran the “new” class. It took the same amount of time and the student success on the same prediction questions was off the chart! (Yes, they were the same questions. Yes, they could have remembered the answers. But I don’t think a change from 51% correct on Monday to 97% on Wednesday can be attributed entirely to memory.)

Perhaps the most interesting part of the poster, for me, was coming up with the title. The potential parallel between Earth/Sun-centered and instructor/student-centered caught my attention (h/t to @snowandscience for making the connection.) With the help of my tweeps, wrestled with the analogy, finally coming to a couple of conclusions. One, the instructor-centered class is like the Sun-centered Solar System (with the instructor as the Sun):

- the instructor (Sun) sits front and center in complete control while “illuminating” the students (planets), especially the ones close by.

- the planets have no influence on the Sun,…

- very little interaction with each other,…

- and no ability to move in different directions.

As I wrote on the poster, “the Copernican Revolution was a triumph for science but not for science education.” I really couldn’t come up with a Solar System model for a student-centered classroom, where students are guided but have “agency” (thanks, Sandy), that is, the free-will, to choose to move (and explore) in their own directions. In the end, I came up with (yes, it’s a mouthful but someone stopped me later to compliment me specifically on the title)

Shifting to a Copernican model of the Solar System

by shifting away from a Copernican model of teaching

Part 3: Example class

When we were organizing the event, Sarah thought it would be interesting to get an actual instructor to present an actual “transformed” class, one that could highlight for the audience (especially the on-the-fence-about-not-lecturing instructors) what you can do in a student-centered classroom. I volunteered the astronomy instructor I was working with, and he agreed. So Harvey (and I) recreated a lecture he gave about blackbody radiation. I’d kept a log of what happened in class so we didn’t have to do much. In fact, the goal was to make it as authentic as possible. The class, both the original and the demo class, had a short pre-reading, peer instruction with clickers (h/t to Adrian at CTLT for loaning us a class set of clickers), the blackbody curves Lecture-Tutorial worksheet from Prather et al. (2008), and a demo with a pre-demo prediction question.

Totally rocked, both times. Both audiences were engaged, clicked their clickers, had active discussions with peers, did NOT get all the questions and prediction correct.

At the CWSEI event, we followed the demonstration with a long, question-and-answer “autopsy” of the class. Lots of great questions (and answers) from the full spectrum of audience members between novice and experienced instructors. Also some helpful questions (and answers) from Carl, who surprised us by coming back to Vancouver for the event.

To top it off, we made the class even more authentic by handing out a few Canadian Space Agency stickers to audience members who ask good questions, jus

t like we do in the real #astro101 class. You should have seen the glee in their eyes. And the “demo” students went all metacognitive on us (as they did in the real class, eventually) and started telling Harvey and I who asked sticker-worthy questions!

Part 4: Peer instruction workshop

The last event of the day was a pair of workshops. One was about creating worksheets for use in class. The other, which I lead, was called “Effective Peer Instruction Using Clickers.” (I initially suggested, “Clicking it up to Level 2” but we soon switched to the better title.) The goal was to help clicker-using instructors to take better advantage of peer instruction. So many times I’ve witnessed teachable moments lost because of poor clicker “choreography,” that is, conversations cut-off, or not even started, because of how the instructor presents the question or handles the votes, and other things. Oh, and crappy questions to start with.

I didn’t want this to be about clickers because there are certainly ways to do peer instruction without clickers. And I didn’t want it to be a technical presentation about how to hook an i>clicker receiver to your computer and how to use igrader to assign points.

Between attending Center of Astronomy Education peer instruction workshops myself, which follow the “situated apprentice” model described by Prather and Brissenden (2008), my conversations with @derekbruff and the #clicker community, and my own experience using and mentoring the use of clickers at UBC, I easily had enough material to fill a 90-minute workshop. My physics colleague @cynheiner did colour-commentary (“Watch how Peter presents the question. Did he read it out loud?…”) while I did a few model peer instruction episodes.

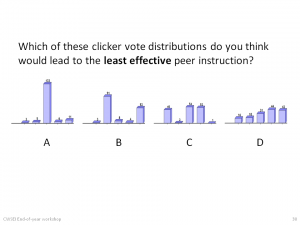

After these demonstrations, we carefully went through the choreography I was following, explaining the pros and cons. There was lots of great discussion about variations. Then the workshop turned to how to handle some common voting scenarios. Here’s one slide from the deck (that will be linked shortly.)

I’d planned on getting the workshop participants to get into small groups, create a question and then present it to the class. If we’d had another 30 minutes, we could have pulled that off. Between starting late (previous session went long) and it being late on a Friday afternoon, we cut off the workshop. Left them hanging, wanting to come back for Part II. Yeah, that’s what we were thinking…

End-of-Year Events

Sure, it’s hard work putting together a poster. And demo lecture. And workshop. But it was a very good for the sharing what the CWSEI is doing, especially the demo class. And I’ll be using the peer instruction workshop again. And it was a great way to celebrate a year’s work. And then move onto the next one.

Does your group hold an event like this? What do you find works?

Wow, sounds like a great conference! Thanks for reporting on it, and doing all that you do :). Our semester just finished up and I am already excited to be planning more “student-centered” curricula for my astronomy and physics classes for the upcoming Fall semester. Looking forward to your future posts and learning more.

Thanks, Carrie. The shift to student-centered classes has been remarkable. You have to be willing to give up the spotlight (hurts the ego a bit). But the reward of seeing the students teach themselves more than pays off. Instead of saying, “I taught them that” you get to say, “I created the opportunity for them to learn that.” I hope you’ll keep sharing your stories, too.

I agree, it sounds like a fabulous conversation. How successful do you think this session was in bringing more people on board in terms of excellent learning, instead of excellent lectures? Education has been plagued with too much of the latter, and not enough of the former.

The example class (Part 3 above) was very successful, I my opinion, because it let the audience experience a multitude of instructional activities which, as you so nicely describe, are about excellent learning, not excellent lecturing. And by “lecturing” I mean the specific activity when the instructor is standing at the front telling the content to the class. There was certainly “a time for telling” but those mini-lectures were just that — mini.

Again, it was seeing it and experiencing it first-hand that I think had the greatest impact. Instructors and others who attended are already aware of the need to shift from instructor-centered to student-centered instruction. Many have probably skimmed through Eric Mazur’s Peer Instruction. As we know, though, there is a big difference between reading about it, experiencing it and implementing it. This example class provided the jump from “read” to “experience”. Veteran instructors, my CWSEI colleagues and I will help committed faculty make the jump from “experience” to “implement”.