The “political spectrum” is a long time topic in high school social studies classes and the parlance of “left-wing/right-wing” is firmly embedded in the minds of most North Americans. However, the left-right dichotomy that is typically used to categorize political views in the media and elsewhere does more obfuscate than illuminate differences in political thought.

In the USA the political spectrum has shrunk to the point that there is effectively no difference between Democrats and Republicans on economics, while there are a few, but only a few, notable differences on social issues. So if you watch Fox News, CNN, etc. you’ll see teleprompter reading pundits making mountains of mole hills when it comes to who’s on the left and who’s on the right—Alan Colms on the left? (At least we don’t have to endure Hannity and Colms any more on FoxNews, although Colms continues to pose on Fox radio).

The terms “Right-wing” and “Left-wing” as applied to politics originated with the French government assemblies in the 18th Century, where the aristocrats sat to the right of the speaker and commoners (the bourgeoisie) to the left.

The oversimplication of political thought to a single scale of left/right is what allows some Americans to actually call Obama a socialist. These folks are sincere in their beliefs about Obama, but the ancient Greeks would have called them called idiots (ἰδιώτης or idiōtēs)—seen as having bad judgment in public and political matters.

Typically jejune public (and pundit) opinions about what constitutes the left and the right makes it difficult for folks to make sense of political positions that fall out of the narrow mainstream—Noam Chomsky and Ron Paul are examples of well known political figures who cannot be accurately characterized on the left/right political binary.

What’s at issue here is not just the accuracy with which we categorize political figures or political views. The left/right binary has the practical effect of forcing political discourse into artificial categories—every political disagreement becomes a two-sided argument, which is the typical cable news or local newspaper paradigm for political news coverage. This strategy works quite well in capitalist democracies, which cultivate the appearance of dissent, choice, and difference on political and social issues, while manufacturing consent amongst the public for policies designed to preserve the interests economic and political elites. The economic bailouts of recent months are a good example of this.

But the left/right binary also alienates, marginalizes, and confuses many people who fail to see a place for their own political views in the “objective” framework of what consitutes politics, so they do not participate (and I’m not talking about voting or elections, but the failure to image themselves as having political agency in the broadest sense of the concept).

Despite a wide variety of models that can provide multidimensional images of political positions, discourse about the political spectrum in the media and many classrooms remains shallow and unidimensional.

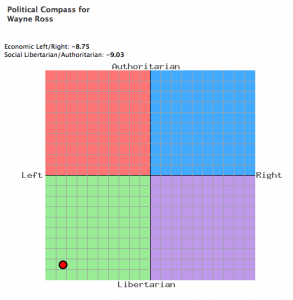

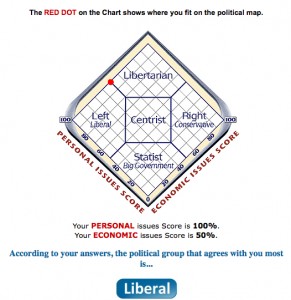

While models (and quizzes) like The Political Spectrum, Pournelle Chart, the Nolan Chart, etc. have their limitations, they can be useful pedagogical tools for teachers who want to encourage their students to think about politics beyond the oversimplified right/left divisions that dominate mainstream media (and this provides students with a good starting point for thinking critically about the MSM and the interests they serve).