Foolish Addendum in Response to Sztulwark

(With many thanks to Ana for organizing the series)

By George Allen, PhD student at the University of California, Irvine

The radical restructuring of the economy towards neoliberalization in the past 40+ years altered the governance of relationships, conduct, self-awareness, values, and feelings. Neoliberal rationality attempts to create a normative subjectivity that is individually responsible for material subsistence by equating the value of individuals and institutions with market rationality, “Because neoliberalism casts rational action as a norm rather than an ontology, social policy is the means by which the state produces subjects whose compass is set entirely by their rational assessment of the costs and benefits of certain acts” (Wendy Brown). Precarity is rationalized and normalized by the dissemination of market logics into every sphere of life, often under the aegis of ‘personal responsibility’.

One of the features of neoliberalism is the way that vocabularies have been co-opted, or as Alessandro Fornazzari writes, “one of the characteristics of post-dictatorship Chile is that the boom in memory becomes undistinguishable from the boom in forgetting”.

With this in mind, in his article “¿Dónde están los amigos y las amigas?” Diego Sztulwark writes emphatically,“¡Manipular los enunciados teóricos para hacerlos funcionar de modo tal que sea la propia vida la que reciba orientación! El amateur apasionado es la versión bricoleury activista del sujeto del poema. Es el militante buscando los medios de darse nuevas posibilidades de vida.” Sztulwark finds “nuevas posibilidades de vida” of subjects becoming non-subjects or non-subjects qua becoming, qua friendship, qua militant readers and amateur bricoleurs.

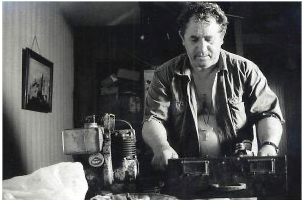

Sztulwark summarizes these theorizations under the banners of a ‘transfiguración perservante’, ’ejercicios espirituales,’—or, put in the language of Colectivo Situaciones, “describir mutaciones subjetivas, y participar de una imaginación política capaz de proyectar formas diferentes del hacer-pensar colectivo” (similarly, Veronica Gago uses the term ‘pragmática vitalista). This line of thinking apropos Fornazarri’s point asks us to think beyond “what is lost?” towards “what is emerging?”. One answer to the latter can be found in the Argentine film Mundo Grúa which tells the story of Rulo, a rotund underemployed handyman–in and around 2000–training to work as a crane operator on a Buenos Aires high-rise. The film questions the language of melancholia—in the neoliberal context—as exclusively contestatory, in favor of documenting a differentiated field of emergent and materializing exhaustion. It utilizes a number of neorealist techniques such as onsite shooting, long takes, deep focus shots, and a cast of non-professional actors—techniques often associated with a representational fidelity to marginalized subjects, repressed histories, and alternative production models that reflect a commitment to social justice. However, the film undermines ‘realist’ aesthetic tendencies with irrational cuts that make characters distant and complicate spatial transparency while at the same time using an observational style not unlike documentary. Film scholar Joanna Page reads this blurring of aesthetic styles as a “provisional form of (auto)ethnography” that seeks to deconstruct the relationship between visibility and knowledge. Writing on the absence of character POV shots in the film, Page argues “As spectators we are denied knowledge of what Rulo is able to see; this technique works to undermine conventional processes of identification” (51).

The appropriation or the faithful mis-reading of texts ala Sztulwark implies a nomadic, fugitive, de-colonial, and anti-institutional movement. However, there is something unsettlingly comfortable about this vision of bricolage, dis-identification, and discontinuity. What kind of consequential choices are left (and what choices does this approach leave us with) to make in a society where commodification, consumer consumption, and capitalistic disjunctive and unequal expansion is the norm? Do the micropolitics of becoming no-neoliberal steer us away from thinking the (re)structure of society? Put differently, what is the congruence of Sztulwark’s redemptive figure of the bricoleur, the friend a venir, the nomad—assemblers for the purposes of disjunction and in the process of dis-identification—with the unequal and discontinuous expansion of capital? Ricardo provides some eloquent thoughts on this.

These structures of relations seek to avoid the fundamental mistake of the Lacanian ‘fool’ who believes in his immediate identity—unlike Zuangh Zi who wonders if he is Zuangh Zi dreaming of being the butterfly or the butterfly dreaming he is Zuangh Zi, the fool believes his identity is his property, not defined by the material and symbolic relations that subtend it. In other words, the ‘fool’ is not far from the psychotic and the narcissist who deny and disavow any mediation of identity. However, even as non-fools, we are the consciousness of the dream–the Lacanian gaze is that which colors Zhuang Zi’s dream. To what degree is Sztulwark’s redemptive reader-bricoleur, friend a venir (etc.) colored by the fantasy of disjunction and the reaction against neoliberal injunctions?

To return briefly to film: Furthering Page’s argument in the vocabulary of Sztulwark, we might say that Mundo Grúa performs an aesthetic coaching, but does not confirm Diego’s ‘ontological optimism.’ Rulo, Mundo Grúa‘s protagonist, is the bricoleur par excellence, but his efforts to assemble and re-arrange the detritus of his lifeworld are constantly thwarted. In one scene, Rulo stops and expresses his admiration for a large film projector. The implications are clearer than they may first appear. Rulo the repairer is fascinated by the smooth-functioning projector just as he views the crane as a space of free-movement. However, Mundo Grúa shows both to be idealistic fantasy spaces, unattainable for and unrelated to Rulo and his lifeworld. On the one hand then, we should reiterate Page’s argument to read the film as anti-representational in the sense that film can not provide direct depictions of life, capital, space, etc. But, it is important to emphasize the way Mundo Grúa, at the aesthetic level, interrupts rather than smoothes and synthesizes depictions through neat cross-cuts. The gambit of Mundo Grúa is one of filmic dysfunction and repair in opposition to the smooth-functioning spaces of commercial cinema.

To return briefly to film: Furthering Page’s argument in the vocabulary of Sztulwark, we might say that Mundo Grúa performs an aesthetic coaching, but does not confirm Diego’s ‘ontological optimism.’ Rulo, Mundo Grúa‘s protagonist, is the bricoleur par excellence, but his efforts to assemble and re-arrange the detritus of his lifeworld are constantly thwarted. In one scene, Rulo stops and expresses his admiration for a large film projector. The implications are clearer than they may first appear. Rulo the repairer is fascinated by the smooth-functioning projector just as he views the crane as a space of free-movement. However, Mundo Grúa shows both to be idealistic fantasy spaces, unattainable for and unrelated to Rulo and his lifeworld. On the one hand then, we should reiterate Page’s argument to read the film as anti-representational in the sense that film can not provide direct depictions of life, capital, space, etc. But, it is important to emphasize the way Mundo Grúa, at the aesthetic level, interrupts rather than smoothes and synthesizes depictions through neat cross-cuts. The gambit of Mundo Grúa is one of filmic dysfunction and repair in opposition to the smooth-functioning spaces of commercial cinema.

There are many ideas that I like about the post and there are things I am not completely following. Maybe we can discuss this later during the seminars.

Perhaps what I liked the most about the post are the moments you write about Mundo grúa (I just watched it and I liked it a lot). While you rightly point out how Mundo grúa depicts a bricoleur character, the ending and conclusion of your post gives me to think. You wrote: “Mundo grúa shows both to be idealistic fantasy spaces, unattainable for and unrelated to Rulo and his lifeworld. On the one hand then, we should reiterate Page’s argument to read the film as anti-representational in the sense that film can not provide direct depictions of life, capital, space, etc. But, it is important to emphasize the way Mundo Grúa, at the aesthetic level, interrupts rather than smoothes and synthesizes depictions through neat cross-cuts. The gambit of Mundo Grúa is one of filmic dysfunction and repair in opposition to the smooth-functioning spaces of commercial cinema”. I would like to comment three things about this:

1. I am not completely convinced by Page’s argument. Page writes that we “are denied knowledge of what Rulo is able to see; this technique works to undermine conventional processes of identification” (51). Yet, at the beginning of the movie, or minutes after it, Rulo and his friend enter into the first construction site. Then, Rulo’s friend says “Nosotros vamos a resolver el tema de la máquina para que podamos seguir laburando”. Seconds before this dialogue, the camera starts a travelling from Rulo’s side (or shoulder) and then it stays in the moment when Rulo’s friend is arguing with the boss of the construction site. This scene, of course, does not allow us to see through the eyes of Rulo but to see from Rulo’s side, that is, not as a provisional “(auto)ethnography” would do but as if we were starting this new job experience with Rulo. Consequently, we, the ones who merely watch the film, also will have a role “repairing the machine”, liking it or not.

2. I don’t think that Rulo wants something too idealistic, actually he just wishes for a “simple” life. The problem is, as you mentioned “Precarity is rationalized and normalized by the dissemination of market logics into every sphere of life, often under the aegis of ‘personal responsibility’”. I would agree with the normalization of precarity but I am not sure if Rulo is completely aware that he has much of “personal responsibility” to solve his problems. In fact, he just worries for keeping a stable job and about his “affects” (having a good relationship with family and friends, finding a new girlfriend). He doesn’t worry about his health, neither about cleaning his house. Rulo is a fool and an optimistic but also, somehow, a cynic. He has no hope, neither he remembers a lot about his past. In fact, he doesn’t want to recover it (it is the girlfriend and other characters who keep remembering Rulo’s glorious days).

3. I like how you close the text. Thinking about this smoothing space you mentioned, I would like to highlight and comment the ending of the film. Rulo gets into the truck that picks him up and, probably, will take him back to the city. Then, the camera shows us two planes, one that locates us, the viewers, as another passenger in the truck, we see what Rulo and the driver see. That plane is like a cinematic screen. Then there is a second plane that shows Rulo’s side face. Finally, the movie dissolves in black, everything is dark yet we see another face, probably Rulo’s face. This face that emerges in the dark, bathed in light, reminds us of a cinema room. At the end of the movie, the experience of the spectator is recreated inside of the movie itself. This recreation may tell us more about our passivity as viewers and for sure about our passivity living in Neoliberalism. After this, some changes may start, or not.

What do you think?

(Sorry for the long comment)

Hey,

Sorry for taking so long in replying, especially to such a well-thought comment. Very kind.

I’ll do better on this, but can’t compete with your sentences: “Si el arte tiene un lugar en la sociedad capitalista, no es sólo el de bombear agua fuera de la nave que se hunde, sino el de dejar de apuntar a las nubes para emprender la línea de fuga ya no hacia el cielo, sino hacia la inmensidad de la tierra.” (HOLY SHIT)

First thing: I don’t really agree with Page’s reading either. One larger discretion I have with her reading at large of so-called ‘dirty realism’ is the focus on ethnography which reads to me like ‘realism’. I’m still not sure how this term is helpful to speak about films other than diagnosing them as pseudo-Diderot encyclopedia style. Then again Bazin would say film is realist par-excellence; the photographer or filmmaker sets up the shot(s), the filmstrip mediates between reality and art, “For the first time, between the originating object and its reproduction there intervenes only the instrumentality of a nonliving agent” (13). Just as a last tangential aside: Bazin’s larger point is not that cinema captures reality transparently, but rather that methods of realism and neorealism introduce ambiguity into the image causing “a more active mental attitude on the part of the spectator” (Bazin, 36). This reminds me a great deal of Ricardo’s comments at the last group about the materialty between lens, ‘frame’, and ultimately discourse.

Anyway, my retort to Page would be that while the (Argentine ‘crisis’ films) are conscious of the problems of mediation associated with representation and marginality, many camera angles, editing, and montages diagnose fundamental features of late capitalist society. What is clear: Rulo is continuously displaced, constantly on the move, and denied any possibility of staying put. He travels all over, but appears to go nowhere. He persists in a world—an economic order—that does not value him or his mode of living.

The film traces mutations of late capitalism in Argentina, yet dismisses the notion that relations between labor and capital were drastically different in the pre-neoliberalism era. What mutations do we get cinematically? I’d argue the film creates the anxiety and expectation for an identifiable cataclysmic event that never becomes actualized in order to question narratives of pre and post crisis.

If you’ll allow me an example or two and to try and answer part of question one, IMO: The first shot is a slow montage of cranes followed by a street level shot of Rulo. In the subsequent sequence, we witness a conversation between Torre, an independently contracted construction worker, and the site supervisor who criticizes him for not adequately repairing and maintaining the construction equipment. Later, while Torre checks one of said failing machines—only to find that it is functioning perfectly—the camera cuts to a low angle shot up the metal cantilevered foundation of a crane then into several long panning shots of Buenos Aires accompanied by Francisco Canaro’s Tango Waltz “Corazón de Oro”. It soon becomes clear that these shots are crane shots, quite literally shots with the camera atop the crane jib.

There’s lots to read into that shot but here’s one: The shot composition of the initial crane montage (after all it’s CRANE WORLD) points to de-territorialized capital accumulation rather than a tragic lamentation about the inverted and deterministic relation between technological progress and surplus labor. The counter-weight, jib, and trolley are framed with voluminous clouds in the background while the diegetic sound of the trolley moving across the jib dominates the soundscape. It is as if we witness capital take flight, departing from the terrestrial airstrip of production into the ethereal atmosphere of speculative accumulation.

Here, you make a wonderful point: In fact, he doesn’t want to recover it (it is the girlfriend and other characters who keep remembering Rulo’s glorious days). Rightly no one will read this but if by chance you are interested, Luis Margani, the actor that plays Rulo, was the bass player of “El Septimo Brigada” that enjoyed relative success in the late 60’s with “Paco Camorra”, a song that tells the story of Paco, a brawny curly-haired man who defends the neighborhood’s weak from bullies. The first refrain of the song goes: “Sale a la calle con su remera/y el pecho afuera/el lleva un pucho en su bocaza/parece un auto feo(viejo) y pesado cuando camina/el es mi amigo y me defiende de los demas”. Like his well-remembered and discarded song, Rulo (and Margani) are discarded members of society, fondly remembered, but anachronistic to the dimensions of the extractive and exhaustive mechanisms of control in contemporary Argentina.

He was a musician, but he meets Milly, the shopowner, and well, falls for her, because she makes ‘milanesas con conciencia’. The implications on different modes of production are here no, ie the possibility of community versus the individualistic, ultimately (shitty) failures to get a job. Note that even in the south the union is fractured.

To try and answer another question with an example from the film: Later in the film, Rulo and Milly attend a film screening. Afterwards, Rulo stops and expresses his admiration for a large film projector. Rulo the repairer is fascinated by the smooth-functioning projector just as he views the crane as a space of free-movement. Perhaps ‘idealistic’ wasn’t the right word but they are fantasy spaces–traditional work even is. Over dinner, Rulo tells his son, Claudio about his new job: “I’ll be way up high, all alone, you see? I can listen to the radio, read my book, if I want to fart, I fart, you see?” The height of the crane suggests the possibilities of economic ascension, and is a fantasy space of individual free movement and leisure—even at the level of the bowels.

Last point, and again I love your reading of the last scene. But I would just add that as his face disappears we once again (as passive viewers like you say) hear another melancholic tango waltz, that given the narrative of the film feels just as ironic as when it plays in the first scene.

A few points to answer this very good question “Put differently, what is the congruence of Sztulwark’s redemptive figure of the bricoleur, the friend a venir, the nomad—assemblers for the purposes of disjunction and in the process of dis-identification—with the unequal and discontinuous expansion of capital? Ricardo provides some eloquent thoughts on this.”

1. Sz is clear about the symptom being a reaction towards the “unequal expansion of capitalism”, what he calls the law of capital as regulating life as a whole [and in re-reading the chapter 15 of capital about the relation between workers and the machine and being reminded about how much Marx discusses bodies of workers, children, health conditions, type of diseases I feel this is a point that has been there for a long time, for Marx symptom as a

literary illness of the body].

2. For Sz there is no guarantee that this symptom is redemptive, rather it can take to overt violence, supporting police killing, anti-immigration sentiments, as is described in vecinismo.

3. I agree that desire needs some problematization, and equating desire with “right” politics is unfortunately not a given, even when the feminist “we are moved by desire” has necessary traction. I feel however that answer thing through Bifo, and the notions of depression as exhaustion worked at the end of the chapter is more productive than thinking it in Lacanian terms that always refolds back to quadruple negations about the fiction of subjectivity (which are productive, but for me only as one small aspect of how desire/politics). I am more interested in thinking about transfeminist reflections, as in the “Liking Women” by Andrea Long Chu.

Long Chu I feel answers the “we are moved by desire” with a “what if desire is not exactly the politics we would like to hold. We could maybe read this if anyone is interested? https://nplusonemag.com/issue-30/essays/on-liking-women/