Soplar arriba, una línea de fuga hacia la tierra: del cuento a la fotografía y luego al cine y viceversa

Notas sobre “Las babas del diablo” (Las armas secretas 1959) de Julio Cortázar y Blow up (1966) de Michelangelo Antonioni

Por Ricardo García

Estudiante en el Doctorado en Estudios Hispánicos en la Universidad de Columbia Británica (University of British Columbia)

Al cuento “Las babas del diablo” (Las armas secretas 1959) de Julio Cortázar y a la película Blow up (1966) de Michelangelo Antonioni, los une más que una relación intertextual. Es decir, no es sólo que la película de Antonioni esté  inspirada en el cuento de Cortázar, sino que ambos textos comparten ciertas interrogantes enrevesadas en ese marco tejido por la modernidad que se extiende hasta nuestros días. Estos textos se preguntan por las posibilidades de un cuento (Cortázar) y una película (Antonioni); por el rol de los productos artísticos en las sociedades capitalistas post segunda guerra mundial; por el rol del escritor, fotógrafo y cineasta; y por el rol de aquellos que participamos de la lectura o del cine. Así, ambos textos son autorreferenciales, juegos de espejos. Con esto, claro está, no es que otras lecturas no sean posibles ni necesarias, sino que la autorreferencialidad de ambos textos y sus implicaciones son las condiciones condicionantes de todas las demás lecturas.

inspirada en el cuento de Cortázar, sino que ambos textos comparten ciertas interrogantes enrevesadas en ese marco tejido por la modernidad que se extiende hasta nuestros días. Estos textos se preguntan por las posibilidades de un cuento (Cortázar) y una película (Antonioni); por el rol de los productos artísticos en las sociedades capitalistas post segunda guerra mundial; por el rol del escritor, fotógrafo y cineasta; y por el rol de aquellos que participamos de la lectura o del cine. Así, ambos textos son autorreferenciales, juegos de espejos. Con esto, claro está, no es que otras lecturas no sean posibles ni necesarias, sino que la autorreferencialidad de ambos textos y sus implicaciones son las condiciones condicionantes de todas las demás lecturas.

Hay más semejanzas que diferencias entre ambos textos. Desde el inicio de “Las babas del diablo” la preocupación central del narrador (o narradores) está en saber cómo contar o relatar una fotografía: “Nunca se sabrá cómo hay que contar esto, si en primera persona o en segunda, usando la tercera del plural o inventando continuamente formas que no servirán de nada”. Esto es, si la fotografía, por la potencialidad de sus imágenes, agota al lenguaje —demás está decir que una imagen vale más que mil palabras—, ¿por qué empeñarse en darle una narración a una fotografía? Igualmente, las letras de los créditos que inauguran Blow up ya sugieren una dificultad al contar en imágenes, pues dentro de la plasticidad del lenguaje, una multiplicidad de imágenes se mueve. El cine mina cualquier sistema de escritura y más aún la escritura, en los créditos, se proyecta siempre sobre una suerte de meseta (en el caso de los créditos, un llano verde, quizás el mismo que aparece el final del filme). Si la narración de una foto no puede ser en su totalidad, porque los sistemas lingüísticos no bastan, la narración cinematográfica, por su parte, ya parece exceder el espacio de la fotografía y de la escritura. Si la foto supera a la escritura, el cine supera a la fotografía. No obstante, en el arte no hay superaciones definitivas, sólo repeticiones, semejanzas, saltos, aceleraciones, intensidades y de vez en cuando algunas diferencias. Estas características son, precisamente, las que sobresalen y se tejen entre “Las babas…” y Blow up. Así, entre ambos textos se retrata el complicado lugar que ocupa la ficción escrita y el cine en contextos tan cercanos pero tan separados por una serie de intensidades y coordenadas afectivas.

No hay sino 7 años entre ambos textos. Aún así, ambos parecen estar hablando de contextos históricos muy diferentes. Demás está decir que Cortázar escribe sobre fotografía pocos años después de la muerte de Robert Walser —quizá el escritor paseante (y no flâneur) por antonomasia— que capturaba en su prosa la vida cotidiana; y que Antonioni dirige y piensa el cine en las épocas aceleradas y turbias de los sesenta, cuando cada noche era la posibilidad de aperturas de múltiples líneas de fuga. En este sentido, ambos textos evocan una misma posición en la modernidad pero afectada a diferente intensidad. En Cortázar, la fotografía tiene siempre una segunda oportunidad de volver a ayudar al niño que se encuentra preso de la muerte para devolverlo a “su paraíso precario”. Esta segunda oportunidad debe ser entendida como la posibilidad crítica que tiene el “arte” al escribir sobre fotografía e incluso al tomar fotografías, sea de forma amateur o profesional. El problema es que después de esta posibilidad crítica, o luego de tratar de bombear agua fuera del barco que se hunde, como dijera Benjamin, la fotografía y todos los que se relacionan con ella quedan a la sombra del diablo, de esa figura de boca de “lengua negra”, que después borra todo en un perfecto foco. Luego de este momento traumático, fotografía, cuento, escritor, fotógrafo y espectador/lector tienen derecho a deleitarse en el cielo, en ese paisaje que siempre ha estado entre paréntesis en el cuento, detrás de las fotos y de los textos, pero que al final de la desgracia causada por ese monstruo baboso y diabólico adquiere un mal sabor, una mirada más, otra falsedad más.

Antonioni por otra parte, no sucumbe ante el diablo. Los acelerados minutos de la antepenúltima secuencia de la película —que pueden ser leídos como el enfrentamiento del fotógrafo de Blow up con el diablo, situación que comparte con el fotógrafo de “Las babas…”—, contrastan con la calma, la pausa y el silencio del final del filme. Thomas, ese nefasto fotógrafo, deja de dar órdenes, deja de creer que salvó a alguien al tomar fotografías, y al contrario se deja llevar por el juego sencillo de la pantomima. Thomas acepta el juego de la pantomima porque el cine regresa a la imagen a su estado de transferencia afectiva lúdica —aunque también haya transferencias violentas en esto, claro. Si el cine tiene un origen, éste es análogo al de la pantomima, pues una imagen no tiene palabras, pero sí ruidos, sonidos y afectos. Mientras que Roberto Michel, en “Las babas…”, se convence de la posibilidad de segundos escapes, pero de la condena de todo aquel que garantice la fuga de los “oprimidos”. Thomas, en Blow up, por su parte, no sólo explota el dilema al que se enfrenta Michel y Cortázar, pues no es ya el paisaje el que aparece en la instancia narrativa de forma repentina, sino que es Thomas el que se desvanece en una superficie cinematográfica luego de dar un paso hacia atrás. Si el arte tiene un lugar en la sociedad capitalista, no es sólo el de bombear agua fuera de la nave que se hunde, sino el de dejar de apuntar a las nubes para emprender la línea de fuga ya no hacia el cielo, sino hacia la inmensidad de la tierra, pues el artista, después de todo es una columna que hiere el cielo con su frente pero con sus manos, pies y pecho, tangencialmente y en movimientos hacia atrás, transforma silenciosamente el mundo.

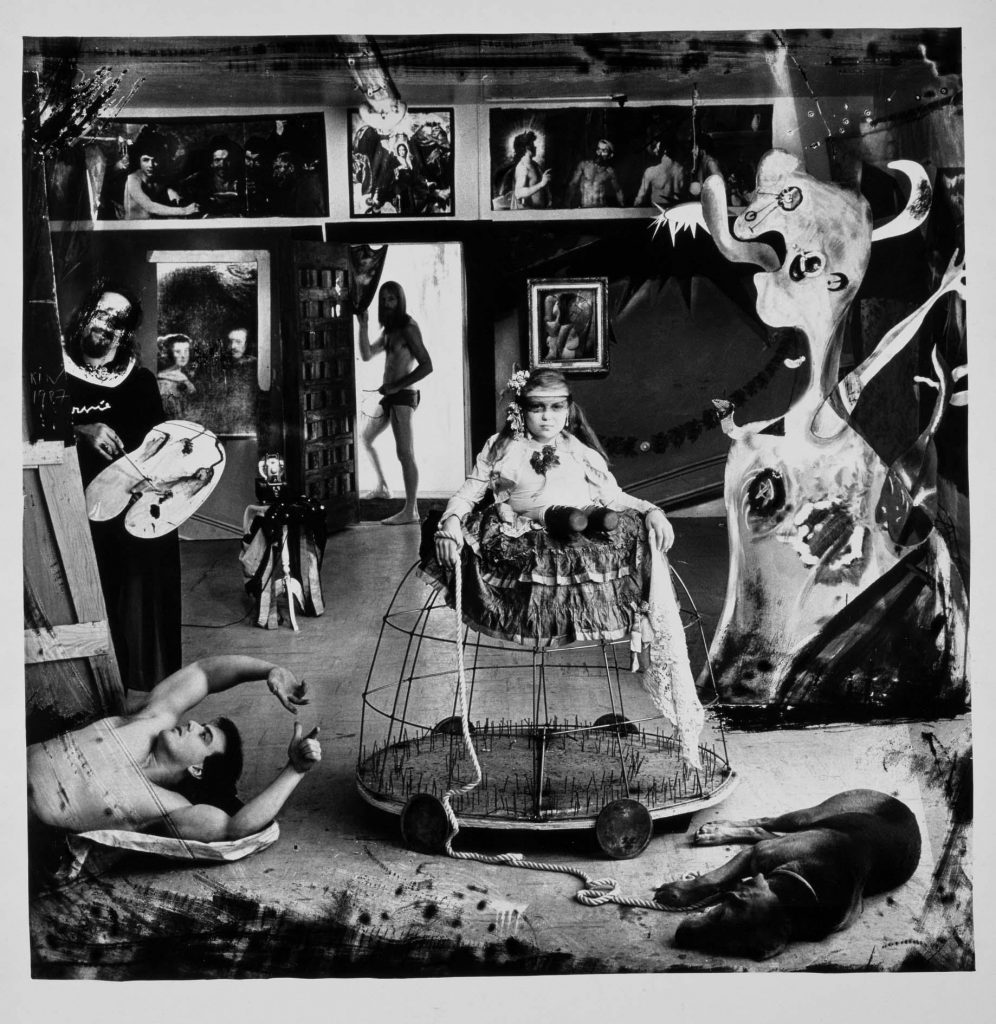

Thanks to everyone who took part in last week’s discussion of Nelson Garrido’s work. It was an interesting and thought-provoking conversation, and we will have many questions for Nelson when he joins us on Wednesday.

Thanks to everyone who took part in last week’s discussion of Nelson Garrido’s work. It was an interesting and thought-provoking conversation, and we will have many questions for Nelson when he joins us on Wednesday.

Thanks to everyone who took part in last week’s discussion of Butler and Appelbaum. There were fewer participants than sometimes, but it was an engaging and productive discussion about representation, photography, and violence.

Thanks to everyone who took part in last week’s discussion of Butler and Appelbaum. There were fewer participants than sometimes, but it was an engaging and productive discussion about representation, photography, and violence. Some notes on “Torture and the Ethics of Photography” (2007) by Judith Butler

Some notes on “Torture and the Ethics of Photography” (2007) by Judith Butler Thanks to everyone who took part in this week’s discussion of Cortázar’s “Las babas del diablo” and Antonioni’s Blow-Up. It was both productive and fun, I felt. We touched on a lot of topics: representation, violence, gender, subjectivity, machines, objectification… Personally, I remain haunted by the movie’s final scene, the invisible tennis ball, the man lost in the park with his camera on the ground.

Thanks to everyone who took part in this week’s discussion of Cortázar’s “Las babas del diablo” and Antonioni’s Blow-Up. It was both productive and fun, I felt. We touched on a lot of topics: representation, violence, gender, subjectivity, machines, objectification… Personally, I remain haunted by the movie’s final scene, the invisible tennis ball, the man lost in the park with his camera on the ground. inspirada en el cuento de Cortázar, sino que ambos textos comparten ciertas interrogantes enrevesadas en ese marco tejido por la modernidad que se extiende hasta nuestros días. Estos textos se preguntan por las posibilidades de un cuento (Cortázar) y una película (Antonioni); por el rol de los productos artísticos en las sociedades capitalistas post segunda guerra mundial; por el rol del escritor, fotógrafo y cineasta; y por el rol de aquellos que participamos de la lectura o del cine. Así, ambos textos son autorreferenciales, juegos de espejos. Con esto, claro está, no es que otras lecturas no sean posibles ni necesarias, sino que la autorreferencialidad de ambos textos y sus implicaciones son las condiciones condicionantes de todas las demás lecturas.

inspirada en el cuento de Cortázar, sino que ambos textos comparten ciertas interrogantes enrevesadas en ese marco tejido por la modernidad que se extiende hasta nuestros días. Estos textos se preguntan por las posibilidades de un cuento (Cortázar) y una película (Antonioni); por el rol de los productos artísticos en las sociedades capitalistas post segunda guerra mundial; por el rol del escritor, fotógrafo y cineasta; y por el rol de aquellos que participamos de la lectura o del cine. Así, ambos textos son autorreferenciales, juegos de espejos. Con esto, claro está, no es que otras lecturas no sean posibles ni necesarias, sino que la autorreferencialidad de ambos textos y sus implicaciones son las condiciones condicionantes de todas las demás lecturas. Thanks to everyone who took part in last week’s discussion with Diego Sztulwark. People have commented to me that it was one of the best sessions we have had to date, and most of the credit for that goes to Ana Vivaldi, for putting together an excellent and very coherent series of readings and conversations in preparation for Diego’s visit. Once again, moreover, I am struck by the continuities in the topics and questions across the last several months, at the very least from Alberto Moreiras’s visit to the present.

Thanks to everyone who took part in last week’s discussion with Diego Sztulwark. People have commented to me that it was one of the best sessions we have had to date, and most of the credit for that goes to Ana Vivaldi, for putting together an excellent and very coherent series of readings and conversations in preparation for Diego’s visit. Once again, moreover, I am struck by the continuities in the topics and questions across the last several months, at the very least from Alberto Moreiras’s visit to the present.