In my previous post I considered some difficulties I’m having in trying to figure out how to evaluate the effectiveness of cMOOCs. In this one I look at some of the things Stephen Downes has to say about this issue, and one research paper that uses his ideas as a lens through which to consider data from a cMOOC.

Stephen Downes on the properties of successful networks

This post by Stephen Downes (which was a response to a question I asked he and others via email) describes two ways of evaluating the success of a cMOOC through asking whether it fulfills the properties of successful networks. One could look at the “process conditions,” which for Downes are four: autonomy, diversity, openness, and interactivity. And/or, one could look at the outcomes of a cMOOC, which for Downes means looking at whether knowledge emerges from the MOOC as a whole, rather than just from one or more of its participants. I’ll look briefly at each of these ways of considering a cMOOC in what follows.

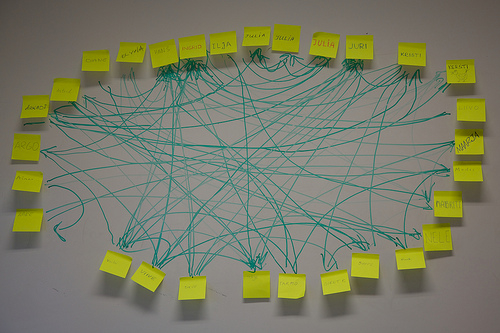

Social Network in a Course by Hans Põldoja. Licensed CC-BY

The four “process conditions” for a successful network are what Downes calls elsewhere a “semantic condition” that is required for a knowledge-generating network, a network that generates connective knowledge (for more on this, see longer articles here and here). This post discusses them succinctly yet with enough detail to give a sense of what they mean (the following list and quotes come from that post).

- Autonomy: The individuals in the network should be autonomous. One could ask, e.g.: “do people make their own decisions about goals and objectives? Do they choose their own software, their own learning outcomes?” This is important in order that the participants and connections form a unique organization rather than one determined from one or a few individuals, in which knowledge is transferred in as uniform a way as possible to all (this point is made more explicitly in the longer post attached here).

- Diversity: There must be a significant degree of diversity in the network for it to generate anything new. One could ask about the geographical locations of the individuals in the network, the languages spoken, etc., but also about whether they have different points of view on issues discussed, whether they have different connections to others (or does everyone tend to have similar connections), whether they use different tools and resources, and more.

- Openness: A network needs to be open to allow new information to flow in and thereby produce new knowledge. Openness in a community like a cMOOC could include the ease with which people can move into and out of the community/course, the ability to participate in different ways and to different degrees, the ability to easily communicate with each other. [Update June 14, 2013: Here Downes adds that openness also includes sharing content, both that from within the course to those outside of it, and that gained from outside (or created by oneself inside the course?) back into the course.]

- Interactivity: There should be interactivity in a network that allows for knowledge to emerge “from the communicative behaviour of the whole,” rather than from one or a few nodes.

To look at the success of a cMOOC from an “outcomes” perspective, you’d try to determine whether new knowledge emerged from the interactions in the community as a whole. This idea is a bit difficult for me to grasp, and I am having trouble understanding how I might determine if this sort of thing has occurred. I’ll look at one more thing here to try to figure this out.

Downes on the quality of MOOCs

Recently, Downes has written a post on the blog for the “MOOC quality project” that discusses how he thinks it might be possible to say whether a MOOC was successful or not, and in it he discusses the process conditions and outcomes further (to really get a good sense of his arguments, it’s best to read the longer version of this post, which is linked to the original).

Downes argues in the longer version that it doesn’t make sense to try to determine the purpose of MOOCs (qua MOOCs, by which I think he means as a category rather than as individual instances) based on “the reasons or motivations” of those offering or taking particular instances of them. This is because people may have varying reasons and motivations for creating and using MOOCs, which need not impinge on what makes for a good MOOC (just like people may use hammers in various ways–his example–that don’t impinge on whether a particular one hammer is a good hammer). Instead, he argues that we should look at “what a successful MOOC ought to produce as output, without reference to existing … usage.”

And what MOOCs ought to produce as output is “emergent knowledge,” which is

constituted by the organization of the network, rather than the content of any individual node in the network. A person working within such a network, on perceiving, being immersed in, or, again, recognizing, knowledge in the network thereby acquires similar (but personal) knowledge in the self.

Downes then puts this point differently, focusing on MOOCs:

[A] MOOC is a way of gathering people and having them interact, each from their own individual perspective or point of view, in such a way that the structure of the interactions produces new knowledge, that is, knowledge that was not present in any of the individual communications, but is produced as a result of the totality of the communications, in such a way that participants can through participation and immersion in this environment develop in their selves new (and typically unexpected) knowledge relevant to the domain.

He then argues that the four process conditions discussed previously usually tend to produce this sort of emergent knowledge as a result, in the ways suggested in the above list. But, properties like diversity and openness are rather like abstract concepts such as love or justice in that they are not easily “counted” but rather need to be “recognized”: “A variety of factors–not just number, but context, placement, relevance and salience–come into play (that is why we need neural networks (aka., people) to perceive them and can’t simply use machines to count them.”

So far, so good; one might think it possible to come up with a way to evaluate a MOOC by looking at these four process conditions, and then assume that if they are in place, emergent knowledge is at least more likely to result (though it may not always do so). It would not be easy to figure out how to determine if these conditions are met, but one could come up with some ways to do so that could be justified pretty well, I think (even though there might be multiple ways to do so).

MOOCs as a language

But Downes states that while such an exercise may be useful when designing a course, it is less so when evaluating one after the fact–I’m not sure why this should be the case, though. He states that looking at the various parts of a course in terms of these four conditions (such as the online platform, the content/guest speakers, and more) could easily become endless–one could look at many, many aspects of a MOOC this way. But I don’t see why that would be more problematic in evaluating a course than in designing one.

Instead, Downes suggests we take a different tack in measuring success of MOOCs. He suggests we think of MOOCs as a language, “and the course design (in all its aspects) therefore as an expression in that language.” This is meant to take us away from the idea of using the four process conditions above as a kind of rubric or checklist in a mechanical way. The point rather is for someone who is already fluent in either MOOC design or the topic(s) being addressed in a MOOC to be able to look at the MOOC and the four conditions and “recognize” whether it has been successful or not. Downes states that “the bulk of expertise in a language–or a trade, science or skill–isn’t in knowing the parts, but in fluency and recognition, cumulating in the (almost) intuitive understanding (‘expertise’, as Dreyfus and Dreyfus would argue)” (here Downes refers to: http://www.sld.demon.co.uk/dreyfus.pdf).

So I think the idea here is that once one is fluent in the language of MOOCs or the “domain or discipline” of the topics they are about, one should be able to read and understand the expression in that language that is the course design, and to determine the quality of the MOOC by using the four conditions as a kind of “aid” rather than “checklist”. But to be quite honest, I am still not sure what it means, exactly, to use them as an “aid.” And this process suggests relying on those who have developed some degree of expertise in MOOCs to be able to make the judgment, thereby making the decision of successful vs. unsuccessful MOOCs come only from a set of experts.

Perhaps this could make sense, if we think of MOOCs like the product of some artisanal craft, like swordmaking–maybe it really is only the experts who can determine their quality, because perhaps there is no way to set out in a list of necessary and sufficient conditions what is needed for a successful MOOC, like it’s difficult (or impossible) to do for a high-quality sword (I’m just guessing on that one). Perhaps there are so many different possible ways of having a high quality MOOC/sword, with some aspects being linked to individual variations such that it’s impossible to describe each possible variation and what aspects of quality would be required for that particular variation. It may be that no one can possibly know in advance what all the possible variations of a successful MOOC/sword are, but that these can be recognized later.

But I’m not yet convinced that must be the case for MOOCs, at least not from this short essay. And I expect I would benefit from a closer reading of Downes’ other work, which might help me see why he’s going in this direction here. It would also help me see why he thinks the process conditions for a knowledge-generating network should be the ones he suggests.

Using Downes’ framework to evaluate the effectiveness of a cMOOC

This is a bit premature, as I admit I don’t understand it in its entirety, but I want to put out a few preliminary ideas. I’m leaving aside, for the moment, the idea of MOOCs as a language until I figure out more precisely why he thinks we should look at them that way, and then decide if I agree. I’m also leaving aside for the moment the question of whether I think the process conditions he suggests are really the right ones–I haven’t evaluated them or the reasons behind them and thus can’t say one way or the other at this point.

The four process conditions

One would have to figure out exactly how to define Autonomy, Diversity, and Openness, which is no easy task, but it seems possible to come to a justifiable (though not final or probably perfect) outline of what those mean, considering what might make for a knowledge-generating network. It might be a long and difficult process to do so, but at least possible, I think. Then, it would be fairly straightforward to devise a manageable (and only ever partial) list of things one could ask about, measure, humanly “recognize” (in the sense of not using a checklist mechanically…though again, I’m not entirely sure what that means) to see if a particular cMOOC fit these three criteria. Again, I have no idea how to do any of this right now, but I think it could be done.

But I am still unsure about the final one: interactivity. This is because it’s not just a matter of people interacting with each other; rather, Downes emphasizes that what is needed is interaction that allows for emergent knowledge. So to figure this one out, one already needs to understand what emergent knowledge looks like and how to recognize if it has happened. I understand the idea of emergent knowledge in an abstract sense, but it’s hard to know how I would figure out if some knowledge had emerged from the communicative interactions of a community rather than from a particular node or nodes. How would I tell if, as quoted above, “the structure of the interactions produce[d] new knowledge, that is, knowledge that was not present in any of the individual communications, but [was] produced as a result of the totality of the communications”? Or, to take another quote from the longer version of the post Downes did for the “MOOC quality project”, how would I know if “new learning occur[red] as a result of this connectedness and interactivity, it emerge[d] from the network as a whole, rather than being transmitted or distributed by one or a few more powerful members”?

I honestly am having a hard time figuring out where/how to look for knowledge that wasn’t present in any of the individual communications, but emerges from the totality of them. But I think part of the problem here is that I don’t understand enough about Downes’ view of connectivism and connectivist knowledge. I knew I should take a closer look at connectivism before trying to tackle the question of evaluating cMOOCs! Guess I’ll have to come back to this after doing a post or two on Downes’ view of connectivism & connective knowledge.

Conclusion

So clearly I have a long way to go to understand exactly what Downes is suggesting and why, before I can even decide if this would be a good framework for evaluating a cMOOC.

In a later post I will look at two research papers that look at cMOOCs through the lens of Downes’ four process conditions, to see how they have interpreted and used these.

I welcome comments on anything I’ve said here–anything I’ve gotten wrong, or any suggestions on what I’m still confused about?

Without a core, not sure you could measure. Distributed data, means distributed evaluation.

Distributed data in what sense, exactly, Pat? You may be right that it would be TOO distributed to measure, but I want to make sure I’m understanding your point here. Which data would be distributed/without a core?

If X teaches Y who teaches Z who teaches A

how would you know about A

Ah, right–yes. But if they were all in the same course (just thinking about that possibility for the moment, even though A might be outside the course) then you could possibly get to A because A might say on a survey or interview that s/he learned something from Z. I’m not sure one needs to get the chain of teaching/learning, necessarily, but rather just to find out that someone learned something from someone else in the course. But for the other alternative, where A is outside the course, then yes, you won’t get that by talking to people in the course. Unless, that is, Z points you to A and A agrees to talk with you about what they learned and how.

This is, indeed, one of the big problems I’ve been thinking about–how do you know all of what happens after and outside the course itself, which might provide really important data on how useful the course was for people inside and outside of it? You could talk to people inside the course, say, 6 months later, but you may not get to person A at all this way. I don’t think there’s any good way to deal with that issue, but rather one could just focus on what was learned by the people in the course, even after the course is done.

A good hypothesis is testable.

As much as I admire Downes, and I do, it strikes me that he is attempting to argue that his hypotheses are, in some senses, untestable, a trait shared in common with religious belief, superstition, and conspiracy theories, and something to be avoided.

Untestable hypotheses are open to confirmation bias (where you give too much weight to seemingly positive outcomes, for example, individual anecdotes of perceived success) and biased thinking ( where negative outcomes are inappropriately discounted, for example, participation rates in cMOOCs, novice user complaints in cMOOCs). The inability to point to an evidence based process, or testable outcome can lead to biased, and baseless positivity. They may rely on anecdotal evidence (testimonials, non generalisaeable case studies, and problematic forms of subjective validation) rather than objective evidence, and measureable outcomes (for example, randomly controlled trials of different subject groups dealing with the same subject matter using differing pedagogies) or ad hoc arguments to falsify their validity.

Communal reinforcement can also be an issue here – the repetition of something that has no evidentiary basis, to such a degree that it becomes an accepted truth.

Self-deception – the discounting of valid facts and information, ad hoc hypotheses to explain away issues, problems and flaws, subjective validation – the assignment of meaning to things on the basis of personal resonance, as opposed to factual correlation, backfire effects, the list of biases and misperceptions is endless.

It strikes me that Downes’s suggestion about how we assess MOOCs may well loan itself to the above issues. It’s a subjective process ( a designer recognising the efficacy of something they may have a vested interest in as a metric for effectiveness is, frankly, a terrible method) and lacks, almost completely, the degree of objectivity required to ensure the absence of biases.

It also strikes me that Downes is suggesting that the degree to which an expert discerns that a MOOC conforms to theory is a good indicator and predictor of it’s effectiveness. This is, essentially, a mode whereby bias is enshrined as good practice.

Surely, the effectiveness of an educational exoperience is best measured not by how that experience conforms ton theory, but by the effects it induces, produces or facilitates amongst those participating. We don’t measure the effectioveness of medicines by how closely they conform to their parent theories, we measure their effectiveness in the field. We don’t measure the success of an economy by how well it mirrors it’s parent theory ( the degree of adherence to Marxist Dialectical Materialism is a terrible metric for this, adherence to perfect fre trade may be equaly bad), we look at the facts, figures, GDP, debt burden etc.

Having designers assess the effectioveness of a MOOC by how closely it tallies with theory is about as useful and rigorous as assessing whether your ulcer has been cured by how well the treatment adhered to it’s own principles. If those principles are unsound, then the problems are compunded.

Good research puts the theory to the test, and good theory loans itself to testing.

I’m not saying the above is the case with Stephen Downes – I think he’s a conscientious, dilligent remarkably intelligent, and dedicated thinker. But Connectivism seems, perhaps, to be a theory that desires to be curiously resistant to testing. And a theory’s falsifiability is a direct measure of it’s usefulness. The issue I’m putting forward here is not that Connectivist thinkers are guilty of any of the above, but, that without falsifiability, and empirical testing the above are impossible to negate, mediate and avoid. And I think Downes’ suggestion for assessment would encourage that possibility.

I guess what I’m saying here is that Connectivism is long on theory, and short on evidence. Theorising can only get you so far. Without empirical evidence, it’s impossible to separate a potentially useful theory from a crackpot one. Without evidence we are lost, and unable to determine truth from untruth, validity from invalidity, and fact from dogma. It strikes me that Connectivism needs to commit to the evidence, and to evidence based research.

What makes a good quality sword is well understood. The art and science of tempering is predictable, empirical, and allows tools fit for purpose to be made reliably. The qualities of soft and hard steel, brittleness, the suitability of different temperatures, tempering processes, and steel mixtures and how they relate to different functions is clear, available, and results in predictable outcomes. A sword is a thing whose quality lies in the degree of understanding it’s maker has of the tested truths of metallurgy, and the precise and proven techniques of forging.

A well made sword is an excellent expression of empirical truths. A badly made sword is the expression of poor understanding. And the truth of it’s construction is eminently testable., If a sword shatters, chips or breaks under duress, we can infer it’s unsuitability. The same testing under duress must also be applied to theory.

Expert assessment of theoretical compliance is not duress. It’s the equivalent of a bad swordmaker assessing their own work.

Really helpful comments here. I think I have some useful replies this time, as opposed to just questions, like on your comment to the last post!

I see the issue with your claim that Downes’ suggestion for evaluating cMOOCs leaves open the very real possibility of bias/lack of objectivity. But I also see where (I think) Downes is coming from–though I’m not sure it applies to cMOOCs. I need to put together another post about someone else’s work I’ve been reading/thinking about/discussing with that person, which is related to this. It’s about using rubrics for marking complex assignments like essays, in which there are multiple possible paths to producing a good quality work that can’t easily be enumerated in a rubric. After talking about these issues with the author of those works (Royce Sadler, who is in Australia and whom I’ve had the good fortune to meet and talk with in person!), I am convinced that he is right in many respects. I’ve blogged about some of his work here and here, but have much more planned. And what he’s saying is similar, I think, to what Downes is saying with trying to use a checklist approach to evaluating a cMOOC–that you may end up constraining your evaluation artificially, or missing some things that aren’t on your checklist but that indicate high quality, etc. Still, I have to do more writing and thinking about this before I can defend it well. So stay tuned.

The idea is that for some things (certainly not all), it may take someone who is immersed in a topic, a field, a practice to be able to recognize good quality x’s, even when they wouldn’t actually measure up as such under some pre-specified rubric because they don’t quite fit the criteria and standards there. Someone applying the rubric mechanically might rate a specific instance of x as not good quality based on the rubric alone. I think this may be the case for writing, which can be done in many different ways effectively, in ways that might surprise one, be beyond what one might have thought would work for an assignment. Sure, there may be some basic criteria that always apply (like grammar, etc.)–and Royce and I are currently discussing what these might be. But such basic criteria might not get you very far. What if, for example, I said in my rubric that students need to have a clear, logical argument in their essays; but that the point being made might actually be strengthened somehow by being a bit fuzzy, ambiguous? Okay, I’m not sure exactly how this would work, but I can imagine it might be possible. Of course, even grammar can be bent effectively (e.g., Joyce? Don’t know b/c I’ve never gotten Joyce at all!).

I was trying to come up with an analogous case with swordmaking, and I admit I may have picked a bad example. I was trying to think of something that was more an art than a science (probably a bad way of putting it–science has many aspects of an “art” as well), and certainly there are objective facts needed about metal tempering, etc., for swordmaking. I was thinking more about the “feel” one has to have as to how long to leave it in the heat, when to pull it out, exactly how to bend the metal, etc., which may not be easily put into words or clear, logical steps. It may be something one can only get by experience and practice, and then one just recognizes when to pull it out of the heat, how exactly to fold it, and the like. Maybe it would have been better to use something like creating artworks, in which it’s easier to see that there may not be a clear set of steps one follows to make a “good” work of art. But that goes a bit far from the cMOOC example, I think.

Re: testing whether a cMOOC conforms to theory vs. whether it is good in other ways–I think of what Downes is suggesting as testing a cMOOC according to how it is designed to work. If one designs a cMOOC according to connectivist principles (which one need not necessarily do…one could of course change the whole idea of a cMOOC into something new; maybe call it something else, etc.), then it makes sense, I think, to evaluate it according to how it was designed to work. It’s like creating learning outcomes for a course and seeing if they were achieved. That doesn’t mean one can’t also recognize or evaluate whether it was successful in other ways, though.

You may be right, though, about connectivism not being rigourously tested (yet?). As noted in my reply to your comment on the last post, I haven’t looked into this enough yet!

Hi Christina,

I look forward to the further posts you are planning. I haven’t read the person you reference, and it’ll be good to get an introduction.

Looks like we disagree on quite a lot here. So, let’s get to the meat of it.

I’m not suggesting that a limiting rubric be applied in quite the way you are discussing. I’m not suggesting a checklist either. I think that, on their own, these could be limiting. Course assessment needs to include numerous things (however difficult they may be to design for and collate).

Student feedback and experiences are key. Assess the theory and not the student and you miss a key driver for informed change and development.

How well does the course facilitate the achievement of learning outcomes (whoever decides them) that are reasonably within the course remit to achieve. This may be difficult, but it’s key, and seems important enough to overcome the obstacles to achieve.

How well designed were course artefacts,and here you will have to stretch past Connectivist thought to describe things like Collaborate seminars, and facilitator practice therein,Task presentation and construction, ease of use and accessibility, overall coherence, suitability for your target audiences ( is it too complex, or too easy, innapropriatley jargon filled, were concepts new or not new to participants).

Participant demographics, and how that interplays with what and how you present your course.

Levels of participation, and engagement with the course, participants, instructors, and artefacts. This may be difficult to guage, but that’s no reason not to guage them. A course that has no method for guaging how people engage with it, or don’t, is like a medicine that has no interest in whether it cures or kills.

Has the course yielded useful outcomes for participants. Here, a mixed approach might be useful, with both quantitative and qualitative data. Again, the participoant experience is key – probably far more important than the designer eye view. Or, to put it another way, your design may be in accord with ho you think it should be, and may match your ideas perfectly, but if that design is of no use, limited use, or detrimental to those participating, it is their experience that will tell you this.

I’m suggesting something already quite nebulous in my own mind, but one that takes hugely into account student experiences and outcomes in a way not suggested by Downes. And, in my experience, assessments of educational experiences that don’t explicitly take account of outcomes and student experiences are gravely flawed, and more likely to remain so.

hmm…just got news that my research prop has been turned down, so I’ll cut this short…

Let’s look at a dfifferent example – Behaviurism, already a farily important educational theory. It works well in some scenarios – skills training, physical skills learning – and not so well in others – higher order thinking, creative pursuits.

If we were to apply a Behaviourist methodology to sculture students, and merely measure how well the course fit the theory, we would be doing our students a grave disservice. The course may be 100% Skinner, with chunking, rewards, disincentives, reinforcers, repetition, shading, all the things that can work so well in other environments, but will be spectacularly disastorous in a sculptural context.

Assessing merely how well the course conforms to theory will allow us to avoid any such considerations, regardless of how expert in Behaviourism the course directors are, and largely assure that the gaping holes in student experiences, development, outcomes, and learning go largely unobserved.

A good, critical and meaningful assessment process is essential to determining the value and usefulness of a course

In addition, although te limits of Bahaviorism are well described, it has been probed, tested, assessed, experimented with under controlled circumstances, and subjected to huge volleys of research and testing, Connectivism has not. As a theory, it is largely unproven, untried, and untested. This lends an additional level of uncertainty and difficulty to what Downes is suggesting. A courses adherence to theory is partially valid if, and only if, the theory is sound.

To put it another way, if you know your theory is rigorous, well worked out, has been tested, trialled, picked apart and experiemented on thoroughly, you still shouldn;t solely rely on the type of compliance Downes suggests to assess it. If it hasn’t gone through that process, the difficulties and problems created are hugely compounded.

Connectivism has not established itself as a sound theory, and has not described itself rigorously enough yet to support the process Downes suggests.

Ok, this clarified a couple of things for me, like that we both agree there should be more in the way of collecting data about student experiences–I wasn’t sure what you meant before by evaluating the theory only…and I don’t know why I didn’t get that, since it makes perfect sense! But anyway, if you see the end of my most recent post (which I wrote a few days ago and just finalized today), you’ll see I ask this question of Downes too. So now I’m understanding better where the lack of objectivity comes in; not so much or just from having some “expert” evaluate a MOOC w/o using a clear rubric, but rather, or at least in large part, from focusing on just measuring how well the course fit the theory–or was “connectivist” in the right way–rather than measuring other indicators of success. I hope I’m getting it right now.

If so, we do actually agree! Downes’ approach seems to focus only on what the nature or purposes of the course were–to create a knowledge-generating network a la connectivism. That may be one way to evaluate a course, namely by asking what one’s objectives were in creating it and seeing if those were met. But there are other things that could indicate success or failure, beyond what one was explicitly trying to do. And in addition, the student experience is, as you note, crucial—even if it does what one was hoping it would do, if it’s a useless experience for others, that is important to know.

I also see your point about testing the theory before trying to evaluate whether a course fits it; who cares, if the theory hasn’t been tested well enough to be sound? I still want to read more of Downes’ work to see how he justifies his views of connectivist knowledge and knowledge-generating networks. I certainly haven’t seen it tested in any deep fashion, but I think Downes refers to other empirical evidence to support his arguments; I just don’t recall at the moment. This isn’t to say that I think connectivism HAS been tested well enough, it’s merely to say that I still don’t know enough to comment on this part.

So at this point, I don’t think we disagree; your arguments make sense to me. So now, onwards to thinking further about how to do this. I agree it requires a mixed-methods approach, but exactly what to measure and how is still something I have yet to work out (and would love to work with you in doing so, if you want to!).

Sorry to hear your research proposal got turned down. That means more work, of course, but hopefully not a lot.

Hi Christina,

looks like we are on the same page here. Not sure why I thought that wasn’t the case. And a good precis from you too.

Frankly, I think working with you would be great. I had hoped to do some of that on OOE, but the research prop fail ( in FUR iating…) is taking what little time I had and flushing it down the toilet.

I’m thinking of taking the marker to the mat on their feedback, so the fail may, or may not stand.

But yes. Let’s work together.

Hi Christina – I’m not sure if this will be of any help to you, but as a result of CCK08 and the two research papers we wrote then, Roy Williams and I have continued to work together to explore what it means to learn in an open learning environment as opposed to a closed/prescribed one. How do learners experience these environments? What factors do designers consider when planning them? Like Stephen we were very aware that in an open MOOC-type environment it is not possible to predict how learners will experience it or what they will learn – so emergent learning is what we have been interested in and have published two papers in IRRODL

Williams, R., Mackness, J. & Gumtau, S. (2012) Footprints of Emergence. Vol. 13, No. 4. International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning.

Williams, R., Karousou, R. & Mackness, J. (2011) Emergent Learning and Learning Ecologies in Web 2.0. International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning. Retrieved from ? Special Issue: Connectivism ? Design and Delivery of Social Networked Learning

In the 2012 paper we developed a framework for exploring learner experiences in different learning environments. We were particularly interested to see if we could identify the factors that would lead to emergent learning. We continue to develop this work – which if you are interested – you can see on this open wiki

http://footprints-of-emergence.wikispaces.com/home

Here is a link to the page where we use the framework to explore learning in CCK08 – http://footprints-of-emergence.wikispaces.com/CCK08+Footprint

Finally in relation to your sentence:

So I think the idea here is that once one is fluent in the language of MOOCs or the ?domain or discipline? of the topics they are about, one should be able to read and understand the expression in that language that is the course design, and to determine the quality of the MOOC by using the four conditions as a kind of ?aid? rather than ?checklist?.

… this has reminded me of work by Glynis Cousin on threshold concepts. She talks about this as having to ‘learn the rules of engagement. I heard her speak not so long ago and wrote this blog post – http://jennymackness.wordpress.com/2012/12/07/threshold-concepts-and-troublesome-knowledge/

In a paper that will shortly be published in the Journal of Online Teaching and Learning –

Waite, M., Mackness, J., Roberts, G., & Lovegrove, E. (under review 2013). Liminal participants & skilled orienteers: A case study of learner participation in a MOOC for new lecturers. JOLT

we have suggested that not only do MOOC participants have to learn the rule of engagement of a MOOC, but that a MOOC itself could be considered a threshold concept.

Not sure if any of this will help.

Jenny

Thanks so much, Jenny! I didn’t know about any of this work, and am very glad to hear what you’re doing and where it can be found. I will definitely read these works, as they sound highly relevant to what I’m thinking about right now.

Christina, in your post you write Downes states that while such an exercise [viewing a network in terms of the 4 process conditions for a successful network] may be useful when designing a course, it is less so when evaluating one after the fact–I’m not sure why this should be the case, though. He states that looking at the various parts of a course in terms of these four conditions (such as the online platform, the content/guest speakers, and more) could easily become endless–one could look at many, many aspects of a MOOC this way. But I don’t see why that would be more problematic in evaluating a course than in designing one. Given that Downes is positing cMOOCs as complex, self-forming network structures, then I think his observation holds. Complex structures often have rather simple starting points that lead to complex and widely-variable outcomes. For instance, a flock of birds or school of fish have few rules for flying or swimming, but these few rules result in the most intricate and variable configurations imaginable, and it is beyond the power of observers to trace back from any given configuration (or outcome) to an initial starting point or to some variation in the exercise of the simple rules. An initial condition in a complex system is necessary for an eventual outcome, but it is hardly sufficient to explain it.

I don’t think this means, however, that you should not use the four process conditions (autonomy, diversity, openness, and interactivity) as metrics for assessing the effectiveness of cMOOCs. They could be particularly enlightening, as Downes suggests, if paired with the six major dimensions of literacy: syntax, semantics, pragmatics, cognition, context and change. This yields a quite granular rubric of 24 cells that should be able to reveal much about the quality of any given cMOOC. You will, of course, need to define the categories in such a way that is responsive to measurement, either qualitative or quantitative.

Of course, you can always drop Connectivism and assess a cMOOC according to your own or to a more well established educational theory. I would love to see how a cognitivist, constructivist, or behaviorist might assess a cMOOC, and I’m a bit curious why there hasn’t been a well-structured assessment of cMOOCs from one of the more established theoretical camps. If cMOOCs are, in fact, having some impact (and I would suggest that this very conversation in this post is evidence that they are), then what do the major educational theories have to say about them? If cMOOCs are a phenomenon that traditional theories cannot address, then is that evidence that we need new theory? I’m not sure.

I’m also not sure that you are so much interested in theory as in practice. I’m not so interested in theory. I’m interested in simple questions: did this experience lead to engagement and transformation? cMOOCs have done that for me and continue to do so. I’m extremely interested to see if you can figure out just how they do that.

Thank you, Keith, for the point about how one might design a cMOOC using the four process conditions, but that by the time it’s done it would be harder to assess them with those conditions b/c it will have developed into a complex system that the initial rules can’t explain. And I left out of my blog post Downes’ argument about the six dimensions of literacy because, frankly, I simply didn’t understand why he was thinking of MOOCs as a language and how the six dimensions of literacy would apply to evaluating them. That’s largely because I am not familiar with these six dimensions, but also because I want to hear more about why these should apply to evaluating cMOOCs. There wasn’t enough argument there, for me, to yet see why it should be that rubric rather than another. Plus, even then, he seems to be arguing that we shouldn’t use them as a rubric but more a kind of guide to recognize the value of a cMOOC (instead of determining it in a mechanistic fashion through checking the cells off one by one).

You’re right that I’m not so much interested in theory as in practice. But once one starts asking the question of “how to evaluate the effectiveness of a cMOOC,” then one has to determine what “effectiveness” means, which can lead one to ask just what are these things supposed to do, which then led me to connectivism. I’m actually most interested in the question of “engagement and transformation”–did they do that for a lot of people? Which ways of doing cMOOCs do that for more people than others? But even those questions are hard to answer with data–how does one determine if that has happened? Ask people their opinions on whether it’s happened? Or can one find other evidence of engagement and transformation? And even deeper, though, are these the right questions to ask if we want to see if a cMOOC has been “effective?” I’m still stuck on what that word “effective” should mean. Perhaps I need to drop it and just ask these other questions, because one can make the case that engagement and transformation, and other such things, are good!

Thanks again for great and thought-provoking comments. I’m in the middle of travelling and moving back to Vancouver from sabbatical in Australia, so am slow in replying or reading any of your stuff! Hotel internet has proved unreliable lately! Finally settling back into Vancouver in the second week of July.