I have been doing quite a few “research reviews” of articles on peer assessment–where I summarize the articles and offer comments about them. Lately I’ve been reading articles on different modes of peer assessment: written, oral, online, face to face, etc. And here, I am going to try to put together what that research has said to see if anything can really be concluded about these issues from it.

In what follows, I link to the blog posts discussing each article. Links to the articles themselves can be found at the bottom of this post.

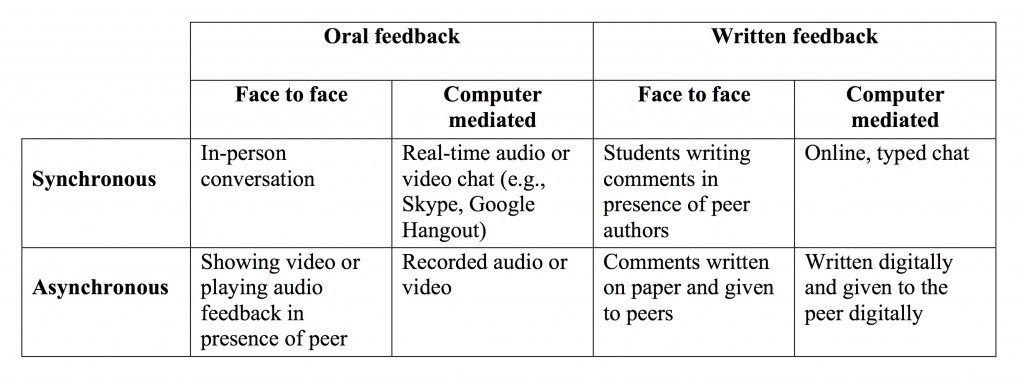

I created PDF tables to compare/contrast the articles under each heading. They end up being pretty small here on the blog, so I also have links to each one of them, below.

Peer feedback via asynchronous, written methods or synchronous, oral, face to face methods

This is the dichotomy I am most interested in: is there a difference when feedback is given asynchronously, in a written form, or when given synchronously, as spoken word face to face? Does the feedback itself differ? Might one form of feedback be more effective than another in terms of being taken up in later revisions of essays?

Do the comments differ in the two modes of peer feedback, and are they used differently in later drafts?

The PDF version of the table below can be downloaded here.

van den Berg, Admiraal and Pilot (2006) looked at differences in what was said in peer feedback on writing assignments when it was written (on standardized peer feedback forms, used for the whole class) and when it was given in oral, face to face discussions. They found that written feedback tended to be more focused on evaluating the essays, saying what was good or bad about them, and less on giving explanations for those evaluative comments or on providing suggestions for revision (though this result differed between the courses they analyzed). In the oral discussions, there was more of a balance between evaluating content, explaining that evaluation, and offering revisions. They also found that both written and oral feedback focused more on content and style than on structure, though there were more comments on structure in the written feedback than in the oral. The authors note, though, that in the courses in which peer feedback took place on early drafts or outlines, there was more feedback on structure than when it took place on later drafts. They conclude: “A combination of written and oral feedback is more profitable than written or oral feedback only” (146).

Hewett (2000) looked at differences in peer feedback between an oral, face to face environment and an electronic, text-based environment. She found that the talk in the oral communication was much more interactive, with students responding to each others’ comments, giving verbal cues that they were following along, and also working together to generate new ideas. The text-based, online feedback was much less like a conversation, with students commenting on the papers at hand but not interacting very much with each other. Perhaps unsurprisingly, then, while the feedback in the written environment was mostly focused on the content of the essay being evaluated, the discussion in the oral environment ranged more widely. Hewett also analyzed essay drafts and peer comments from both environments to see if the peer discussion and comments influenced later drafts of essays. She found that in the oral environment, there was more use in students’ work of ideas that came up in the peer discussion about others’ essays, or that one had oneself said. Hewett concludes that a combination of oral discussion and asynchronous, written comments would be good, using the former for earlier stages of writing–since in oral discussion there can be more talk in which students speculate about wider issues and work together to come up with new ideas–and the latter for revisions focused more on content.

What are students’ views of each mode?

A PDF version of the following table can be downloaded here.

Figl et al. (2006) surveyed students in a computer science course who had engaged in peer assessment of a software project in both the face to face mode as well as through an online, asynchronous system that allows for recording of criticisms as well as adding comments as in a discussion board. There wasn’t a clear preference for one mode over another overall, except in one sense: about half of the students preferred using the face to face mode for discussion within their own teams, and with their partner teams (those they are giving feedback to and receiving feedback from). There was not as much discussion of the feedback, whether within the team or with the partner teams, in the online format, students reported, and they valued the opportunity for that discussion. Figl et al. conclude that it would be best to combine online, asynchronous text reviews with face to face activities, perhaps even with synchronous chat or voice options.

The study reported in Guardardo & Shi 2007 focused on asynchronous, written feedback for the most part; the authors recorded online, discussion-board feedback on essays and compared that with a later draft of each essay. They wanted to know if students used or ignored these peer comments, and what they thought of the experience of receiving the asynchronous, written feedback (they interviewed each student as well). All of the students had engaged in face to face peer feedback before the online mode, but the face to face sessions were not recorded so the nature of the comments in each mode was not compared. Thus, the results from this study that are most relevant to the present concern are those that come from interviews, in which the students compared their experiences of face to face peer feedback with the online, written, asynchronous exchange of feedback. Results were mixed, as noted in the table, but quite a few students said they felt more comfortable giving feedback without their names attached, while a significant number of students preferred the face-to-face mode because it made interacting with the reviewer/reviewee easier. The authors conclude that “online peer feedback is not a simple alternative to face-to-face feedback and needs to be organized carefully to maximize its positive effect” (458).

Cartney 2010 held a focus group of ten first-year students in a social work course who had engaged in a peer feedback exercise in which essays and comments on essays, as well as follow up discussion, was to take place over email. Relevant to the present concern is that the focus group discussion revealed that several groups did not exchange feedback forms via email but decided to meet up in person instead in order to have a more interactive discussion. Some groups did exchange written, asynchronous, online feedback, citing discomfort with giving feedback to others to their “faces.” The author concludes that there may be a need to use more e-learning in curricula in order for students to become more accustomed to using it for dialogue rather than one-way communication. But I also see this as an indication that some students recognized a value in face to face, oral, synchronous communication.

Peer feedback via electronic, synchronous text-based chat vs. oral, face to face methods

This dichotomy contrasts two sorts of synchronous methods for peer feedback and assessment: those taking place online, through text-based systems such as “chats,” and those taking place face to face, orally.

Do comments given synchronously through text-based chats differ from those given orally, face to face? And do these two modes of commenting affect students’ revisions of work differently?

A PDF version of both of the tables below can be downloaded here.

Sullivan & Pratt 1996 looked at two writing classes: in one class all discussions and peer feedback took place through a synchronous, electronic, text-based chat system and in the other discussions and peer feedback took place face to face, orally. They found that writing ability increased slightly more for the computer-assisted class over the traditional class, and that there were differences in how the students spoke to each other in the electronic, text-based chat vs. face to face, orally. The authors stated that the face to face discussion was less focused on the essay being reviewed than in the online chats (but see my criticisms of this interpretation here). They also found that the electronic chats were more egalitarian, in that the author did not dominate the conversation in them in the same way as happened with the face to face chats. The authors conclude (among other things) that discussions through online chats may be beneficial for peer assessments, since their study “showed that students in the computer-assisted class gave more suggestions for revision than students in the oral class” (500), and since there was at least some evidence for greater writing improvement in the “chat” class.

Braine 2001 (I haven’t done an earlier summary of this article in my blog) looked at students in two different types of writing classes in Hong Kong (in English), similar to those discussed in Sullivan & Pratt (1996), in which one class has all discussions and peer assessment taking place orally, and the other has these taking place on a “Local Area Network” that allows for synchronous, electronic, text-based chats. He looked at improvement in writing between a draft of an essay and a revision of that essay (final version) after peer assessment. Braine was testing students’ ability to write in English only, through the “Test of Written English.” He found that students’ English writing ability improved a bit more for the face-to-face class than the computer-mediated class, and that there were significant differences in the nature of discussions in the two modes. He concluded that oral, face-to-face discussions are more effective for peer assessment.

Liu & Sadler 2003 contrasted two modes of peer feedback in two composition classes, one of which wrote comments on essays by hand and engaged in peer feedback orally, face to face, and the other wrote comments on essays digitally, through MS Word, and then engaged in peer discussion through an electronic, synchronous, text-based chat during class time. The authors asked about differences in these modes of commenting, and whether they had a differential impact on later essay revisions. Liu & Sadler were not focused on comparing the asynchronous commenting modes with the synchronous ones, but their results show that there was a higher percentage of “global” comments in both of the synchronous modes, and a higher percentage of “local” comments in the asynchronous ones. They also found that there was a significantly higher percentage of “revision-oriented” comments in the oral discussion than in the electronic chat. Finally, students acted more often on the revision-oriented comments given in the “traditional” mode (handwritten, asynchronous comments plus oral discussion) than in the computer-mediated mode (digital, asynchronous comments plus electronic, text-based chat). They conclude that for asynchronous modes of commenting, using digital tools is more effective than handwriting (for reasons not discussed here), and for synchronous modes of commenting, face to face discussions are more effective than text-based, electronic chats (219-221). They suggest combining these two methods for peer assessment.

Jones et al 2006 studied interactions between peer tutors in an English writing centre in Hong Kong and their clients, both in face to face meetings and in online, text-based chats. This is different from the other studies, which were looking more directly at peer assessment in courses, but the results here may be relevant to what we usually think of as peer assessment. The authors were looking at interactional dynamics between tutors and clients, and found that in the face-to-face mode, the relationship between tutors and clients tended to be more hierarchical than in the electronic, online chat mode. They also found that the subjects of discussion were different between the two modes: the face-to-face mode was used most often for “text-based” issues, such as grammar and word choice, while in the electronic chats the tutors and clients spoke more about wider issues such as content of essays and process of writing. They conclude that since the two modes differ and both serve important purposes, it would be best to use both modes.

Implications/discussion

This set of studies is not the result of a systematic review of the literature; I did not follow up on all the other studies that cited these, for example. A systematic review of the literature might add more studies to the mix. In addition, there are more variables that should be considered (e.g., whether the students in the study underwent peer assessment training, how much/what kind; whether peer assessment was done using a standardized sheet or not in each study, and more).

Nevertheless, I would like to consider briefly if these studies provide any clarity for direction regarding written peer assessment vs. oral, face-to-face.

For written, asynchronous modes of peer assessment (e.g., writing on essays themselves, writing on peer assessment forms) vs. oral, face-to-face modes, the studies noted here (van den Berg, Admiraal and Pilot (2006) and Hewett (2000)) suggest that in these two modes students give different sorts of comments, and for a fuller picture peer assessment should probably be conducted in both modes. Regarding student views of both modes (Figl et al. (2006), Guardardo & Shi (2007), Cartney (2010)), evidence is mixed, but there are at least a significant number of students who prefer face-to-face, oral discussions if they have to choose between those and asynchronous, written peer assessment.

For written, synchronous modes of peer assessment (e.g., electronic, text-based chats) vs. oral, face-to-face, the evidence here is all from students for whom English is a foreign language, but some of the results might still be applicable to other students (to determine this would require further discussion than I can engage in now). All that can be said here is that the results are mixed. Sullivan & Pratt (1996) found some, but not a lot of evidence that students using e-chats improved their writing more than those using oral peer assessment, but Braine (2001) found the opposite. However, they were using different measures of writing quality. Sullivan & Pratt also concluded that the face-to-face discussions were less focused and effective than the e-chat discussions, while Braine concluded the opposite. This probably comes down in part to interpretation of what “focused” and “effective” mean.

Liu & Sadler (2003) argued that face-to-face modes of synchronous discussion are better than text-based, electronic, synchronous chats–opposing Sullivan & Pratt–because there was a higher percentage of “revision-oriented” conversational turns (as a % of total turns) in the face-to-face mode, and because students acted on the revision-oriented comments more in the traditional class (both writing comments on paper and oral, face-to-face peer discussion) than in the computer-mediated class (digital comments in MS Word and e-chat discussions). Jones et al. (2006) found that students and peer tutors talked about different types of things, generally, in the two modes and thus concluded that both should be used. But that study was about peer tutors and clients, which is a different situation than peer assessment in courses.

So really, little can be concluded, I think, from looking at all these studies, except that it does seem that students tend to say different types of things in different modes of communication (written/asynchronous, written/synchronous, oral/face-to-face/synchronous), and that those things are all valuable; so perhaps what we can say is that using a combination of modes is probably best.

Gaps in the literature

Besides more studies to see if better patterns can emerge (and perhaps they are out there–as noted above, my literature search has not been systematic), one gap is that no one, so far, has considered video chats, such as Google Hangouts, for peer assessment. Perhaps the differences between those and face-to-face meetings might not be as great as between face-to-face meetings and text-based modes (whether synchronous chats or asynchronous, written comments). And this sort of evidence might be useful for courses that are distributed geographically, so students could have a kind of face-to-face peer assessment interaction rather than just giving each other written comments and carrying on a discussion over email or an online discussion board. Of course, the problem there would be that face-to-face interactions are best if supervised, even indirectly, so as to reduce the risk of people treating each other disrespectfully, or offering criticisms that are not constructive.

So, after all this work, I’ve found what I had guessed before starting: it’s probably best to use both written, asynchronous comments and oral, face-to-face comments for peer assessment.

Works Cited

Braine, G. (2001) A study of English as a foreign language (EFL) writers on a local-area network (LAN) and in traditional classes, Computers and Composition 18, 275–292. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S8755-4615(01)00056-1

Cartney, P. (2010) Exploring the use of peer assessment as a vehicle for closing the gap between feedback given and feedback used, Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 35:5, 551-564. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02602931003632381

Figl, K., Bauer, C., Mangler, J., Motschnig, R. (2006) Online versus Face-to-Face Peer Team Reviews, Proceedings of Frontiers in Education Conference (FIE). San Diego: IEEE. See here for online version (behind a paywall).

Guardado, M., Shi, L. (2007) ESL students’ experiences of online peer feedback, Computers and Composition 24, 443–461. Doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.compcom.2007.03.002

Hewett, B. (2000) Characteristics of Interactive Oral and Computer-Mediated Peer Group Talk and Its Influence on Revision, Computers and Composition 17, 265-288. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S8755-4615(00)00035-9

Jones, R.H., Garralda, A., Li, D.C.S. & Lock, G. (2006) Interactional dynamics in on-line and face-to-face peer-tutoring sessions for second language writers, Journal of Second Language Writing 15, 1–23. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jslw.2005.12.001

Liu, J. & Sadler, R.W. (2003) The effect and affect of peer review in electronic versus traditional modes on L2 writing, Journal of English for Academic Purposes 2, 193–227. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1475-1585(03)00025-0

Sullivan, S. & Pratt, E. (1996) A comparative study of two ESL writing environments: A computer-assisted classroom and a traditional oral classroom, System 29, 491-501. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0346-251X(96)00044-9

Van den Berg, I., Admiraal, W., & Pilot, A. (2006) Designing student peer assessment in higher education: analysis of written and oral peer feedback, Teaching in Higher Education, 11:2, 135-147. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13562510500527685