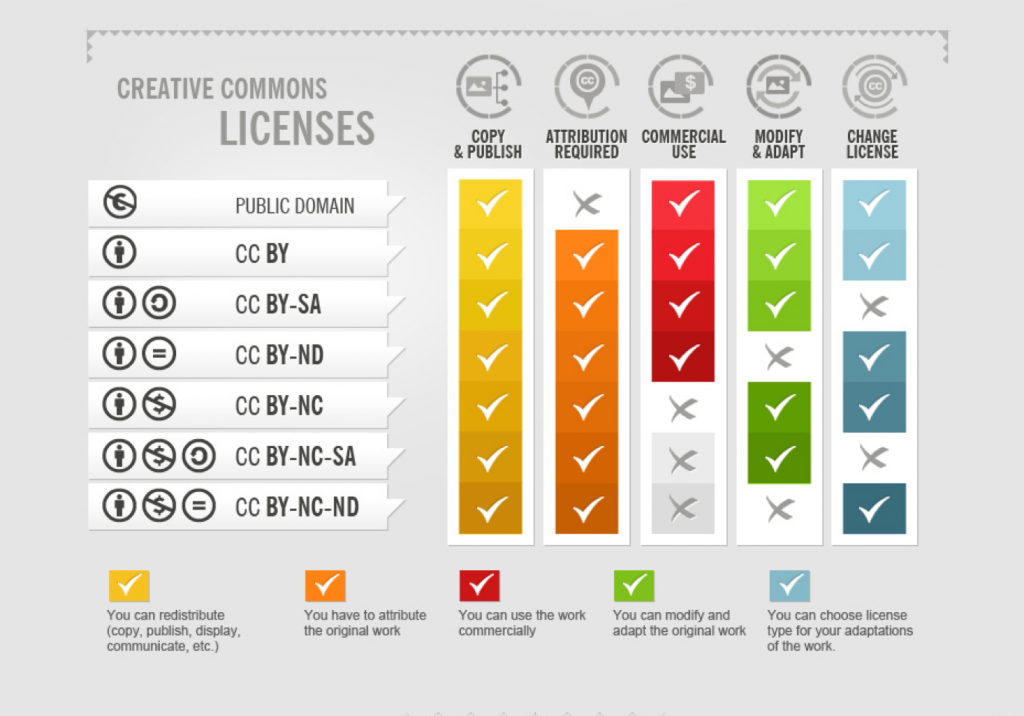

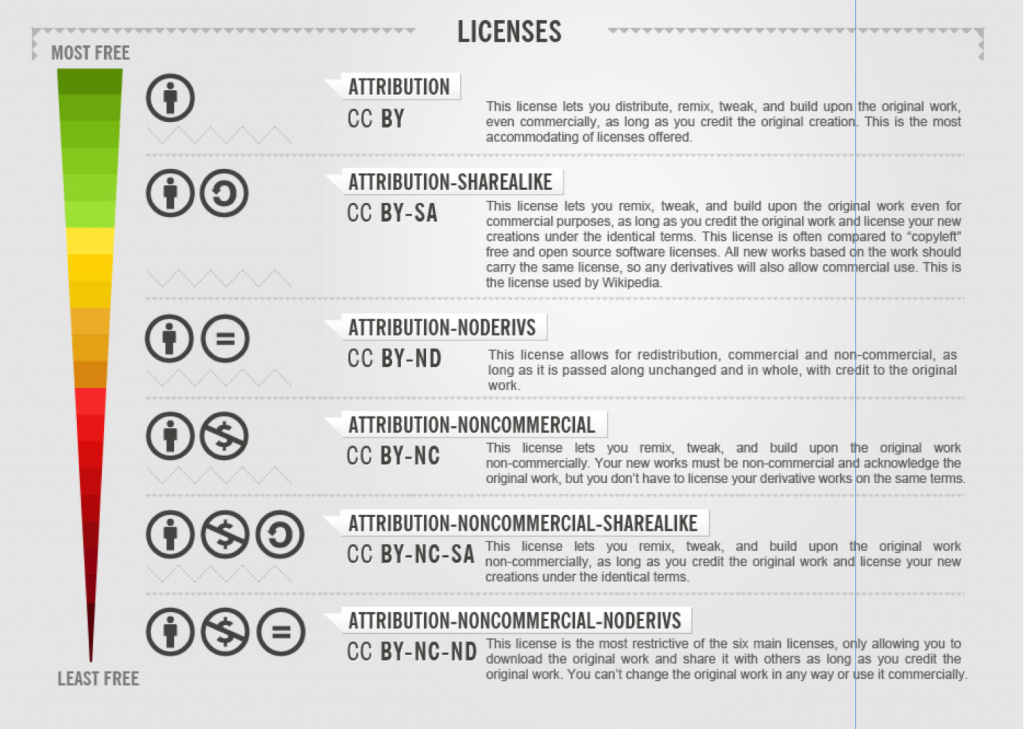

In the Creative Commons Certificate course I’m taking, there has been some discussion in the course slack channel about the difference between remixes and collections, in response to an assignment that asked us to create a remix (not a collection)–see my previous post for the assignment and the Story Map on Epicurus I created.

When one puts different CC licensed works together, when does one create a remix thereby, and when a collection?

Remixes/adaptations

The Creative Commons FAQ explains a “remix” as an “adaptation,” and defines an adaptation as:

An adaptation is a work based on one or more pre-existing works. What constitutes an adaptation depends on applicable law, however translating a work from one language to another or creating a film version of a novel are generally considered adaptations.

In order for an adaptation to be protected by copyright, most national laws require the creator of the adaptation to add original expression to the pre-existing work. However, there is no international standard for originality, and the definition differs depending on the jurisdiction.

Elsewhere the Creative Commons FAQ says about adaptations:

Generally, a modification rises to the level of an adaptation under copyright law when the modified work is based on the prior work but manifests sufficient new creativity to be copyrightable …

Note that an adaptation does not include redistributing a work in a new format: “Note that all CC licenses allow the user to exercise the rights permitted under the license in any format or medium.”

So just like many things in copyright law, what makes something an adaptation or remix depends on where you are, and even then it’s not necessarily 100% clear. The general idea seems to be that you are changing a work to enough of a degree that you can be said to be adding something original that can be copyrightable.

Collections

A collection, by contrast, would then seem to be using works (more or less?) unaltered and putting them together in some fashion.

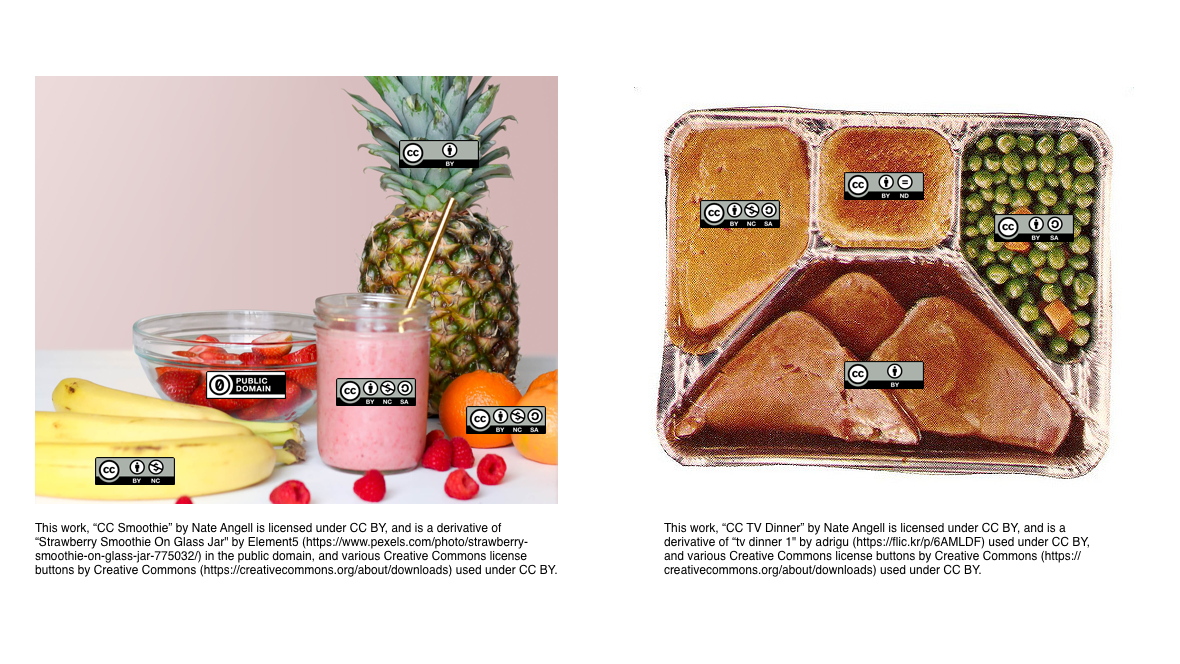

Nate Angell provided a nice metaphor for the difference between remixes and collections, likening remixes to smoothies and collections to TV dinners.

A “TV dinner” open work is when one collects separate works together and redistributes that collection, but clearly separates each work and its attribution. In this case, one is not “remixing” works, but rather curating them and offering that curation to others. Like with real TV dinners, you can still consume each ingredient by itself because they are served with clear boundaries separating each.

A “smoothie” open work is when one mixes together parts or the whole of one work with parts or wholes of other works to create a new, derivative work that includes material from many sources. Like with real smoothies, you can’t easily separate the different ingredients once they are blended together.

My lingering questions

This TV dinner vs smoothie description makes a lot of sense to me, but I wondered if one has to create a work where you can’t tell the “boundaries” between the other works in it, for it to be a remix. So, for example, if I add some arrows and text to an image, I can tell the boundaries between the original image and the text and arrows I’ve added on top of it, but I still think maybe I’m creating an adaptation or derivative work. Maybe it depends on how much I’ve added and whether those additions make the new work rise to the level of being copyrightable or not.

Let’s think about the images Nate created above as an illustration. He has taken original images and added CC license buttons to them. Are those images adaptations or collections?

Similarly, I created a few new images for the Story Map on Epicurus I created for one of the assignments in the CC certificate course. For some of them I just added circles and text to maps. For others I put several icons together into a single image. For one (showing the chronology of Socrates, Plato and Epicurus) I put three images together, added borders, and text. I am not sure if all of these are truly adaptations or not.

Question about using unaltered images in a set of slides

In the Creative Commons Certificate Slack channel I asked a few questions:

The more I think about this [the difference between remixes and collections], the more questions I have. So, for example, I thought that including an unaltered, CC licensed image in a slide show (maybe altering the size but nothing else) would mean I’m making a collection: the image (or images if there are multiple ones) plus my text plus maybe some other images. Then I could use images with licenses different from the license I gave to my slide show so long as I said “except where otherwise indicated, these slides are licensed CC BY” (e.g.).

Someone else posted in the channel that yes, that sounds right (I don’t want to quote or identify them because I haven’t asked permission!). I then continued:

But then a remix could also be considered a work where you take other works and put them together in a way that involves a degree of creativity and creation of something that could itself be copyrighted (I think), which I then think applies to my slide show because I use images in a way that they weren’t originally intended and I put them together with other images and text in a way that is copyrightable (or else how could I give it all a CC license?).

So is my slide show (as described above) a remix? And if so, can I not use, for example, CC BY SA images if I want to license the slides CC BY?

My issue here is: I could only rightfully put a CC license on my slides if they’re copyrightable, which would mean I have added enough originality to make them so. And if that’s the case, then it seems I’ve created a remix rather than a collection, and I couldn’t do the thing where I’m separating out the CC BY-SA image from the rest of the slides and license the slides overall CC BY. It seems I’d have to license them CC BY-SA.

I had an interesting conversation with someone on Slack about this, where we talked about how maybe what one is licensing with the CC BY on the whole slide deck is the stuff in between and around the CC BY-SA image. This person also noted: does it makes sense that if one remixed someone else’s image (maybe by changing the colour and adding text), then that one image must dictate the license of the whole deck of, e.g., 100 slides? This person noted that one could instead remix the image separately, post it on another site (like Flickr), license it CC BY-SA (if the original image were CC BY-SA) and say that the license for the remix was worked out before it entered the slide deck…and then again, what the CC BY on the slide deck is licensing is what else is in it besides that image.

Someone else on Slack helpfully noted that it’s useful to look at the license legal codes for complicated questions. For example, here is the legal code for CC BY-SA 4.0.

Here is what I then said on Slack, after looking at the legal code:

I found this sentence from the legal code for BY-SA particularly helpful:

“Adapted Material means material subject to Copyright and Similar Rights that is derived from or based upon the Licensed Material and in which the Licensed Material is translated, altered, arranged, transformed, or otherwise modified in a manner requiring permission under the Copyright and Similar Rights held by the Licensor.”

So, if I’m just using the “licensed material” (e.g., the original image) as is and not translating it, altering it, transforming it, or otherwise modifying it then I can put it into my slide show just as it is and say it’s licensed CC BY-SA even though my overall slides are licensed CC BY.

So I think I figured out the answer to my question about a slide show. But I am still not certain about how much adapting is needed for something to rise to a full adaptation/remix!