Yes, it’s another post on ChatGPT! Who needs another post? I do! Because one of the main reasons I blog is as a reflective space to think through ideas by writing them down, and then I have a record for later. I’m also very happy if my reflections are helpful to others in some way of course!

Like so many others, I’ve been learning a bit about and reflecting on GPT-3 and ChatGPT, and I must start off by saying I know very little so far. I took a full break from all work-related things from around December 20 until earlier this week, and I plan to do some deeper dives to learn more in the coming days and weeks. I should also say that though this is focused on GPT, that’s just because it’s the only one I’ve looked into at this point.

Mainly why I’m writing this post is to do some deeper reflection on why I have many writing assignments in my philosophy courses, what I hope they will do for students. And as I was thinking about this, I started reflecting on the role of writing in philosophy more generally, since philosophy classes teach…philosophy.

Academic philosophy and writing

Okay, a whole book could be written about the role of writing in academic philosophy. Here are just a few anecdotal reflections.

Philosophy as I have been trained in it and practice it in academia is frequently focused on writing. We also speak orally, and that’s really important to the discipline as well. Conversations in hallways, in classes, with visiting speakers, at conferences, etc. are all crucial ways we engage in thinking, discussing, making arguments as well as critiquing and improving them. This may not be agreed upon by all, but I still think writing is more heavily emphasized. Maybe I think that partly because for hiring, tenure, and promotion processes what seems to count most are written works rather than oral presentations, lectures, or workshops. Maybe it’s because most of what we do when we do research in philosophy is read written works by others and then write articles, chapters, or books ourselves.

Oral conversations tend to be places where philosophers test out ideas, brainstorm new ideas, give and receive feedback, iterate, discuss, do Q&A, and communicate (among other purposes). Interestingly, even at philosophy conferences, at least the ones in North America I’ve attended, it’s common to read written works out loud during research presentation sessions. (This is not the case for sessions focused on teaching philosophy, which are often more workshop-like and focused more on interactive activities.) For me it can be very challenging to pay attention for a long time by just listening, and I personally appreciate when there are slides or a handout to help keep one’s thinking on track and following along. Writing again! Oral conversations and presentations are also not accessible to all, of course, and one alternative (in addition to sign language) is writing, either in captions or transcripts.

Writing is also a way that some folks (maybe many?) think their way through philosophical or other arguments and ideas. As noted at the top of this post, this is certainly the case for me. I have to put things into words in order to really piece them together and form more coherent thoughts, and though that can be done orally (say, through a recording device), for me it works better in writing.

From these brief reflections, here are some of the likely many roles of writing in doing philosophy. This is not a comprehensive list by any means! And it’s likely similar for at least some other disciplines.

- Writing to think and understand: Sometimes summarizing works by others helps one to understand them better (e.g., outlining premises and conclusions from a complicated text, or recording what one thinks are the main claims and overall conclusion of a text). In addition, sometimes writing helps one to understand better one’s own somewhat vague thoughts, to clarify, delineate, group them into categories, think of possible objections, etc. (That’s what I’m doing with this blog post)

- Writing to communicate: communicating our own ideas and arguments, and taking in communications by others of theirs by reading them (as one means; communication of philosophical ideas and arguments can happen in other ways too!). Communicating the ideas and arguments of others, as often happens in lectures in philosophy classes, or when summarizing someone else’s argument before critiquing it and offering a revised version or something new.

- Writing as a memory aid: Taking notes when reading texts, or listening to a speaker, or during class. Writing down notes to remind oneself what to say when teaching, or giving a lecture or conference presentation, or facilitating a workshop. Writing one’s thoughts down to be able to return to them later and review, revise, etc. (as in the last point).

The point of these musings is that at least in my experience, a lot of philosophical work, at least in academia, is done in or through writing, even though many of us also engage in non-written discussions and communications. And for me, this is important context to consider when thinking about teaching philosophy and writing, and what it may mean when tools like ChatGPT come onto the scene.

Teaching philosophy and writing

I came to the thoughts above because I was thinking about how it is very common in philosophy courses to have writing assignments–frequently the major assignments are essays in one form or another–and I started to reflect on why that might be. It could be argued that writing is pretty well baked into what it means to do (academic) philosophy, at least in the philosophical traditions I’m familiar with. So it could make sense that teaching students how to do philosophy, and having them do philosophical work in class, means teaching them to write and having them write! (Of course, academic philosophy is not all of what philosophy can be…this is another area on its own, but I think at least some of the focus on writing in philosophy courses may be related to its focus in academic philosophy.)

And like many academic and disciplinary skills, it can be helpful to build up towards philosophical writing skills by practising the kinds of steps that are needed to do it well. So, for example, in philosophy courses we often ask students to review an argument presented by someone else (usually in writing) and summarize it, perhaps by outlining the premises and conclusion. Then maybe in a later step we’ll ask them to offer questions or critiques of the argument, or alternative views or approaches, all of which are important parts of doing philosophy in the traditions in which I’m immersed. In later stages or upper-level courses we’ll ask students to do research where they gather arguments from multiple sources on a particular topic, analyze them, and offer their own original contributions to the philosophical discussion.

All of this is similar to the sort of work professional philosophers do in their own research, and to me just seems like natural ways of doing philosophy given my own experience. It’s just that we do it at different levels and often in a scaffolded way in teaching.

However, mostly I teach introductory-level courses, and the number of students who will go on to do any more philosophy, much less become professional philosophers, is relatively small. So personally, I including writing assignments not just because they are part of what it means to do philosophy (though it’s partly that), but also because I think the skills developed are useful in other contexts. Being able to take in and understand arguments by others (whether textual or otherwise), break them down into component parts to help support both understanding and evaluation, evaluate them, and revise or come up with different ideas if needed, are I think pretty basic and important skills in many, many areas of work and life. I think this (or something like it) may (?) continue to be the case as AI writing tools become more and more ubiquitous, but of course I’m not sure, and that’s a question for further thought.

Process and product

When teaching it’s much more about the learning and thinking that happens through the process of writing activities that’s important. The essay or parts of an essay that result are not the critical pieces. After all, if I ask 100 or more students to analyze the same argument and produce a set of premises and conclusions (for example), the resulting summary/analysis of the argument isn’t the important piece there, especially when there will be many, many of them. It’s the learning and thinking that’s happening to get to that point. The summary is there as a stand-in for the thinking and learning. And in some cases it’s the same for the critiques, feedback, or alternative ideas that students may offer in response to someone else’s argument–what I may care about more is what they’re learning through doing that thinking rather than the specific replies they produce. Many will be really interesting and thought-provoking. Others may be will be similar across multiple students. Depending on the level of the course and the learning outcomes, all of these may be fine as results; what I care about is that they are putting in the thought and reflection to hone skills of (to use a too-well-worn term) “critical thinking.”

When I think about it this way, I wonder what is the purpose of the actual essay or paragraph or outline of an argument that I assign in courses. It’s often not the actual end product (though sometimes it is, particularly for upper level or graduate courses). The end product is mostly a vehicle and proxy for me as a teacher to review whether the thinking, reflecting, and learning is taking place.

So, thinking about the several ways writing is used in philosophy noted in the previous section, I think largely I’m assigning writing for the purposes of thinking and understanding, and also communicating–maybe to other students, to me, to TAs, etc. And my assumption, when marking writing, is that the written text is actually communicating the student’s thinking and understanding, that the communication and the thinking are linked.

Teaching writing in philosophy, and ChatGPT

One of the things that the emergence of ChatGPT really emphasizes for me is that that end product isn’t really a good communication vehicle to assess whether the thinking and understanding has taken place. This really hit home for me through a post on Crooked Timber by philosopher Eric Schliesser. Schliesser notes that several professors have said that the essays produced by ChatGPT are decent enough to earn a passing grade, if not higher. “But this means that many students pass through our courses and pass them in virtue of generating passable paragraphs that do not reveal any understanding,” Schliesser points out.

This made me think: the essay may not only not be a reliable communication of the student’s own thinking (which we knew already due to concerns about plagiarism, people paying others to write their essays, etc.), but may not be communicating thinking and understanding at all. The link between the two can be completely severed. (This is assuming, as I think it’s safe to assume at this point, that tools like ChatGPT are not doing any thinking or understanding…I know this is a philosophical question but for the moment I’m going to go with the seemingly-reasonable-at-this-point claim that they’re not.)

In one respect, this is an extension of previous academic integrity concerns: if what we want to be assessing is the student’s own thinking and understanding, then ChatGPT and the like are similar issues in that a student could submit something that does not communicate their own understanding–it’s just that in this case, rather than communicating the understanding someone, somewhere, at some point had, it’s not communicating understanding at all.

But of course, we have academic integrity concerns for a reason, and for me it’s not just that I want to be able to tie the writing to the individual student for the sake of integrity and fairness of assessment (though that is important too), it’s also that I want to engage students in activities that will develop skills that will be useful to them in the future. And it’s seeming more and more the case that the written texts I have used in the past as a vehicle to review whether they have developed those skills is less and less useful for that purpose.

At the moment, I can think of a few options, some of which could be combined for a particular assignment or class:

- Continue to try to find ways to connect the writing students do out of class to themselves–an extension of academic integrity approaches we already have. These can include:

- using plagiarism checkers (which right now I think do not work with tools like ChatGPT

- comparing earlier, in-class writing to later, out-of-class writing

- quizzing students orally on the content of their written work

- asking students to do multiple steps for writing assignments, some of which could be done in class, and also ask them to explain their reasoning for the choices they are making (this one from Julia Staffel–see more from her below)

- Find other ways for students to show their thinking and understanding than assigning written work done outside of class.

- E.g., Ryan Watkins from George Washington University suggests (among other things) having students create mind maps (which ChatGPT can’t do … yet?) and holding in-class debates where students could show their thinking, understanding, and skills in communicating.

- Julia Staffel from the University of Colorado Boulder talks in a video posted on Daily Nous about alternative approaches in philosophy courses, such as in-class essays, oral exams, oral presentations (synchronous or recorded), and assignments based on non-textual sources such as podcasts or videos (but that only works until the tools can start using those as source material).

- Use ChatGPT or similar in writing assignments

- Numerous people have also suggested assignments in which students need to work with ChatGPT; if we think of it like a helper tool that can generate some early ideas for us to build on or critique, or that can provide summaries of others’ work that we can evaluate for ourselves, etc., then we could still be supporting students to build some similar kinds of skills as earlier writing assignments.

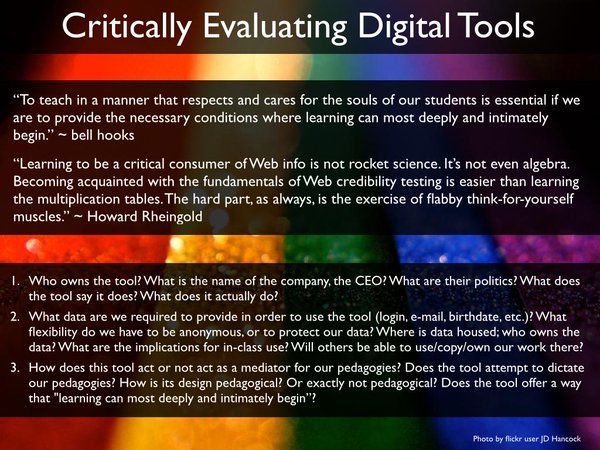

- Still, inspired by a blog post by Autumm Caines, I’m wary of doing this until I look more into privacy implications, who has access to what data and how it’s used. Autumm also talks about the ethics of requiring students to provide free labour to companies to train tools like this. And what happens when the tool or ones like it are no longer offered for free?

- Finally since ChatGPT can already mark and provide feedback on its own writing (albeit not perhaps the best), it’s not clear to me that having students have the tool draft something and then comment on it/revise it is going to necessarily get around the tie-the-work-to-a-mind issue.

A number of the ideas above have to do with doing things synchronously, in a way that the instructor and/or TAs can witness. Some are alternative approaches to providing evidence of thinking and understanding done outside of class that work for now, just based on what the tech can do at the moment. And maybe those will continue to work for some time, or maybe not. It feels a bit like trying to do catch-up with an ever-changing landscape.

I have many more thoughts, but this blog post is already too long so I’ll save them for later. For now, a takeaway is that maybe one of the things that I’ll need to do in the future is spend more time in class on activities that develop and allow students to communicate the thinking and understanding I’m hoping to support them in. If I have to assess them (which I do), then I’d like to bring the communication and the thinking parts back together. I want to think through pros and cons of a number of suggestions noted above, and similar ones, particularly around what they are actually measuring and whether it’s connecting to my learning goals in teaching (which, incidentally, is an important exercise to do for out-of-class writing too of course!).

I also have some ill-formed thoughts about the value of teaching students to write philosophy essays at all, if they can be written so easily by a bot that doesn’t think or understand. But that’s for another day!