What does it mean to be an animal? To be a human? And what does reading have to do with anything?

Animal studies and the environmental humanities are ideas that are increasingly familiar to 21st-century readers; viewed here through the lens of some of the finest and most intriguing literary works from the premodern Romance world, with important interactions with other literatures around the whole world and influences on them, and spanning a range of forms: from short poems to encyclopaedias, from fables to bestiaries, from saints’ miracles to dramatic multimedia satires.

What, where, and when is this “Romance World I: Medieval to Early Modern” of the course title? We’ll be in places where the linguistic relatives of today’s Catalan, French, Italian, Occitan, Portuguese, and Spanish are used; our two set texts are from the 12th and the 16th centuries CE, but we’ll be talking about manuscript and multimedia cultures from the 6th century onwards … and before and after, from an “in the middle” in the sense of not being in the beginning nor in End Times … and elsewhere: potentially adventuring anywhere in a Global Middle Ages, depending on where students’ interests take us.

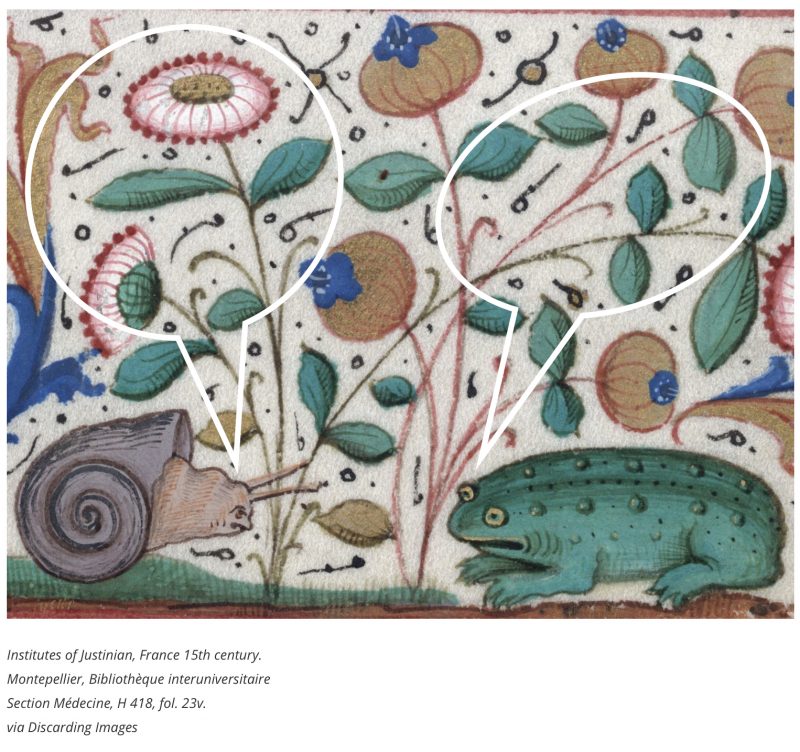

We will start small: listening to a frog in a 12th-century Troubadour poem in Old Occitan by Marcabru, “Bel m’es quan li rana chanta.” We will revisit this frog at the end of the course, to see how our readings have changed along the way, and how we have changed through them.

Our two set / required texts in the main body of the course are originally in 12th- and 16th- century French:

- The Lais of Marie de France, ed. and trans. Glyn S. Burgess (Penguin Classics, any edition)

- Montaigne, The Complete Essays, ed. and trans. M. A. Screech (Penguin Classics, any edition)

Through them, we will meet animals in associated works from France, Italy, and Spain (and other areas where Romance vernaculars are spoken, in a multilingual world; our 12th-c. set text, for example, is from England). There will be reading about animals, of animals, and physically on animals (through online digitised manuscripts and books in the library); shape-shifting; animals reading (and speaking, interacting, and otherwise showing evidence of sentience and thinking); and reading humans as animals (via Montaigne). Along the way, readings and student work may converse with—for example—wolves, dogs, foxes, bears, birds, bees, donkeys, horses, deer, cats, squirrels, rabbits, snails, unicorns, hedgehogs, lions, chickens, sheep, fish, whales, otters, beavers (and of course frogs).

All texts will be worked on in English translation, though students will have the option, if they wish, of using versions in the original (or a modernized variant) in their final projects and in their public humanities knowledge contributions—the next posts that you will see here below—in “Humanimals Reading: A Local Bestiary.”