I participated in a “conference” that took place entirely on Twitter March 29, 2018–PressEd 2018, about using WordPress in Education. It was a very interesting format: all presentations were series of 10-15 tweets over the course of 15 minutes, leaving time for questions at the end.

All of the tweets were on the #pressedconf18 hashtag, so you can see them by searching that tag.

Or you can see each of the presentations as Twitter moments.

I did a presentation about connecting student blogs together through syndication, in the Arts One program I taught in for many years. You can see the Tweets from this below.

I really liked this conference, for a few reasons.

- It didn’t feel like something I had to travel to in order to get a full experience, which meant it didn’t feel like some people got a different and better experience than others.

- It was something I could dip into and out of during the day and didn’t feel bad about it because I knew it would all be available later.

- The sessions were in small enough chunks to digest without feeling overwhelmed. One could get bite-sized thoughts and ideas that could percolate later. And there are lots of links to go explore for the things one is particularly interested in.

- I was able to keep exactly on time because I created the tweets beforehand and then I scheduled them to be once a minute during my 15 minutes. I didn’t go over time or feel like I wished I had just five more minutes, for maybe once in my life.

- The small character count kept me from being too wordy or trying to cover too much (which are issues I usually have). I have to say, though, this would have been much more challenging for me back in the 140-character limit days.

I didn’t get many questions or comments afterwards, but that was okay … I felt like others were dipping in and out just like I was, and plus–the sessions were really close to each other in timing and there wouldn’t have been time to have long conversations on the hashtag without busting into someone else’s series of tweets!

Here are the tweets I sent… And looking back, I realize I really should have had more pictures or screen grabs or something. These are all just text and links, and many others had nice visuals. I hadn’t been thinking this way, but it makes sense to consider these tweets kind of like slides for a presentation, and I wouldn’t have slides that are *only* text. So I embedded some images here in my post, even though I didn’t do it in the original tweets.

Oh well…next time! I hope this format is used again by someone/some group (something for me to consider myself!).

1. Hello #pressedconf18! I’m Christina Hendricks & I teach philosophy at University of British Columbia in Vancouver, BC, Canada. I’m also Deputy Academic Director of the Centre for Teaching, Learning & Technology.

Excited to participate in my first Twitter conference!

— Christina Hendricks (@clhendricksbc) March 29, 2018

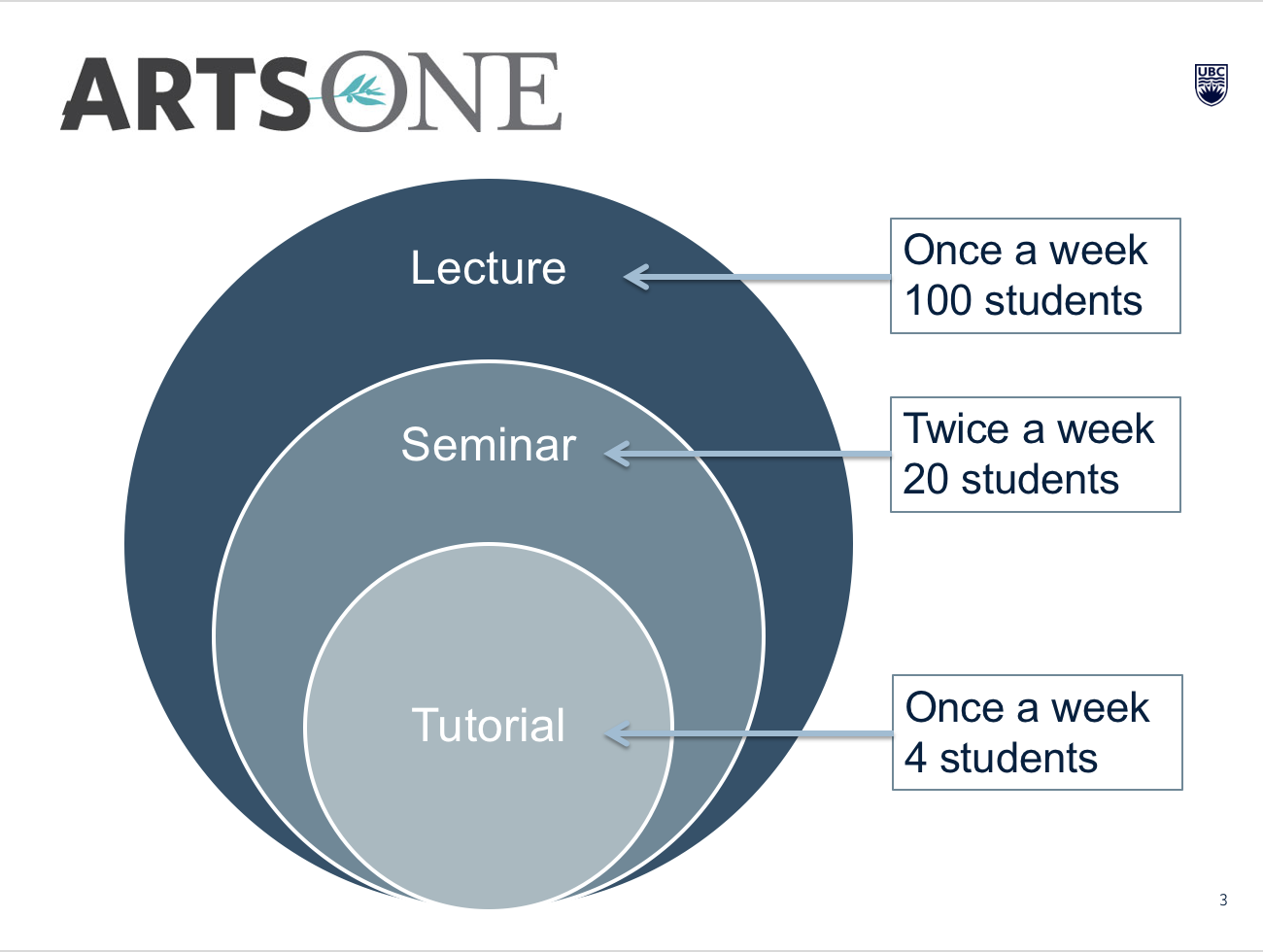

2. For many years I taught in a team-taught, interdisciplinary program for first-year students called Arts One: https://t.co/1ZSs2qngkz.

It has about 100 students, broken up into groups of 20 that meet in seminars with 1 of the profs on the team.#pressedconf18

— Christina Hendricks (@clhendricksbc) March 29, 2018

3. All students read the same texts (mostly in the humanities) & attend the same lecture each week, but meet in their 20-student seminar groups twice a week (plus also in groups of 4 once a week to peer review essays). #pressedconf18

— Christina Hendricks (@clhendricksbc) March 29, 2018

4. So beyond the 1 lecture/week, students are separated into their smaller groups even though reading the same things.

A colleague started a site called “Arts One Open” a few years ago: https://t.co/FyYi6yGbda

Has student & prof blogs, recorded lectures, & more.#pressedconf18

— Christina Hendricks (@clhendricksbc) March 29, 2018

5. Arts One Open was partly meant as an open version of the course for others to follow along (had live streamed lectures at first). But we didn’t have people-hours to support this fully. An important part of the site is the syndicated blogs.#pressedconf18

— Christina Hendricks (@clhendricksbc) March 29, 2018

6. Students in some of the seminar groups in Arts One (only those with profs who wanted to participate) either created own blogs or wrote on a single group blog. My students created their own blogs, syndicated to our own seminar class site: https://t.co/z3RTlFc459#pressedconf18

— Christina Hendricks (@clhendricksbc) March 29, 2018

7. Then, all blog posts from students in separate seminar groups (& some professors’ blogs) were syndicated to Arts One Open site (using FeedWordPress): https://t.co/z3RTlFc459

So students reading same texts in different groups could see what others blogged about.#pressedconf18

— Christina Hendricks (@clhendricksbc) March 29, 2018

Ooops–the link in the above tweet is wrong. It should be: http://artsone-open.arts.ubc.ca

8. A cool thing is that student posts, professor posts, recorded lectures are all on same “footing” insofar as they are all posts in one big stream, findable thru tags. We all contributed to the class/curriculum together & the site reflects that.#pressedconf18

— Christina Hendricks (@clhendricksbc) March 29, 2018

Tag cloud of tags on Arts One Open (you can find student & prof blog posts, plus lecture recordings, plus podcasts through these tags)

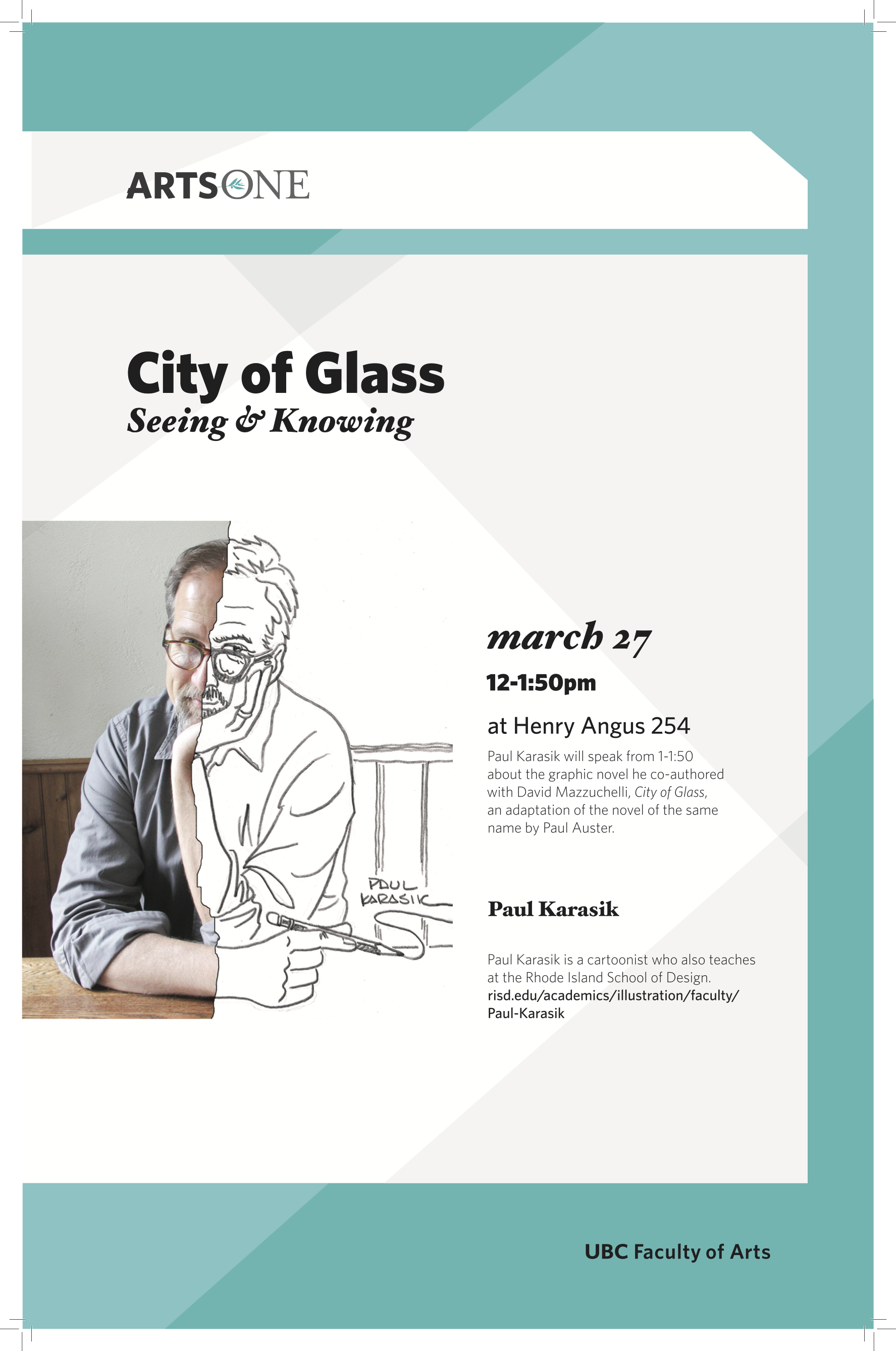

9. Most posts are available publicly (students had option of making them private to class). This led to: 1 of authors on our reading list (Paul Karasik) read posts from previous year & replied; he then came to campus the next year & gave guest lecture. Was great!#pressedconf18

— Christina Hendricks (@clhendricksbc) March 29, 2018

10. I don’t feel we got as much uptake from students on interacting across seminar groups as would have been good. Needed to promote that more. Would have been good to have more profs blogging too but that was just if/when they chose. #pressedconf18

— Christina Hendricks (@clhendricksbc) March 29, 2018

11. Also, I stopped teaching in the program this year and the project hasn’t been kept up since I left, sadly. That’s why there aren’t any new blog posts since a year ago. But infrastructure is there in case someone wants to pick it back up!#pressedconf18

— Christina Hendricks (@clhendricksbc) March 29, 2018

12. I used a similar system of syndicated blog sites in a large-ish intro to philosophy course in the past, for smaller discussion groups of 25 students who were all part of the same big course. But it was too hard to make & upkeep all those separate sites.#pressedconf18

— Christina Hendricks (@clhendricksbc) March 29, 2018

13. So now in my philosophy course all students post on the same site but I use categories to separate their posts out into smaller discussion groups. See “discussion summaries” here: https://t.co/Qr0r8A3FlP#pressedconf18

— Christina Hendricks (@clhendricksbc) March 29, 2018

14. There are a couple of minutes left if anyone has questions! And thanks so much for listening/reading!#PressEDconf18

— Christina Hendricks (@clhendricksbc) March 29, 2018