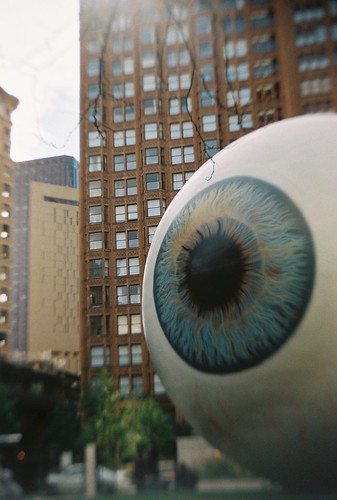

“Panopticon,” cc licensed ( BY ) flickr photo shared by chad_k

“Panopticon,” cc licensed ( BY ) flickr photo shared by chad_k

A year or two ago a student came into my office and told me about some podcasts he had been listening to, which consisted of some lectures by a well-known philosopher as part of one of his university courses. The student then asked me why I didn’t put my lectures out on podcasts, or make them public in some other way.

I don’t remember what I said. But I do remember what I felt: apprehension. And some fear. I couldn’t imagine, at the time, doing such a thing.

Now I can, and largely through my experience in ETMOOC I’ve become very interested in the idea of “openness” in education and want to start doing some of this myself. Of course, “open” means different things in different contexts (here’s a nice post explaining some of them, and here’s an even larger list of various “opens”) , but I’m considering things such as posting and licensing many of my course materials for re-use, as well as possibly opening up a course to outside participants the way Bryan Jackson did with his high school Philosophy course.

The value of open education

There are plenty of good things about opening up your teaching and learning materials, space, interactions, etc. Bryan Jackson explains something good that happened as a result of having an open Philosophy course, in this video. Barbara Ganley had an interesting experience from a writing assignment in her class posted publicly on a blog (see “A Writing Assignment Gets Personal,” on this site).

David Wiley, in a presentation on open education called “Openness, Disaggregation, and the Future of Education” (the keynote for the 2009 Penn State Symposium for Teaching and Learning) gave several examples of things he had done recently in his courses to make them more open. Among them:

- He required that all students’ written work must be made public on the course blog. One result of this was that Stephen Downes—a prominent Canadian researcher, blogger, cMOOC facilitator, and editor the popular newsletter OLDaily (online learning daily)–had read some of the work and highlighted a few posts, sending them out to thousands of his followers in the OLDaily newsletter. Wiley noted that the following week, much of the students’ writing got longer, better, and more thoughtful. Such improvement came much better this way than just encouraging students to write more carefully and address issues more deeply through the instructor’s comments.

- He wrote up a script for a fake sitcom (situation comedy) tv show, to show differing viewpoints on opening up “learning objects” (what are now called open educational resources, I think). He put this up on a course wiki, and some of the graduate students in the course started writing in new characters in order to give even more perspectives. They hadn’t asked or said they were going to do it, but just did. This was, he stated in the talk, a great way to get students involved in creating learning materials for the course itself.

My experiences in ETMOOC are good evidence as well: I now have a much wider network of people to talk to about teaching and learning, and educational technology, because this course is open to anyone who wants to join and participate. I have more comments on my blog, many more twitter interactions, more people to help answer questions (I just ask the Twittersphere and answers come quickly), more links to helpful resources for my own thinking and teaching and learning, and more.

These are just a few examples of good things that can come from opening up education. I’m certain there are many more.

In addition, ETMOOC-ers said some good things about the value of openness in a recent Twitter chat:

@courosa A1 I think people adding to and sharing others work INCREASES the value of the work.Reach more people #etmchat

— Debbie Vane (@debvane) March 7, 2013

@courosa The work then becomes our work instead of owned&controlled by 1person Collective work: collaborate not compete#etmchat

— lisa domeier (@librarymall) March 7, 2013

q2) One strength of the open movement is that it becomes a powerful tool useful in promoting creative collaboration a la #etmooc #etmchat

— Paul Signorelli (@trainersleaders) March 7, 2013

@kooner_j Good point – I’m quite sure my work has improved because I know that it will be read beyond the classroom. #etmchat

—Alec Couros (@courosa) March 7, 2013

I can see many benefits to opening up my teaching and learning more than I’m already doing, and I expect there are more that I can’t even currently imagine.

So was I reticent before, when my student asked about podcasting my classes, only because I didn’t see these benefits then? I don’t think so.

Fear and Openness

There are many ways of making one’s courses more “open,” including just posting one’s course materials for others to see (e.g., written materials, digital presentations, video or audio of lectures); giving the materials a Creative Commons license that allows others to reuse, repurpose, and build on them; live streaming your class meetings publicly; all the way to opening out the course to any participants who want to join (see Alec Couros‘ Social Media & Open Education course as an example, as well as Bryan Jackson’s high school philosophy course noted above). The concerns I bring up below apply to all of these, but mostly to the last two.

The apprehension I felt at the idea of podcasting my lectures wasn’t just the usual fear of being in front of a camera or having one’s voice go out into the wider world; I was a college radio DJ in university and grad school, and am don’t mind speaking into the void with the knowledge that many people (or none) might be listening. Video is still a little tough for me, but I’m quickly getting over that.

It wasn’t just a lack of confidence, a sense that no one would want to listen to my lectures when they have access to those of people who are much more expert than me on the topics they’re discussing (though there was some of that too).

There was something about potentially being watched, being observed, at any time, by anyone; but mostly, by those who could have significant influence over my future. It’s not that I worry my teaching isn’t very good, or that I think bad things would happen if those who can affect my employment see most or all of what I do in class. I actually have (and have had) fantastic colleagues, and every time I’ve had a peer visit a class it has ended up being a very positive experience, complete with helpful advice–much of which I still vividly remember and use.

I think it was partly that in having my courses be “open” it’s as if I could be undergoing a peer review of teaching at any time, all the time.

Which means, of course, (being a Foucault scholar) that I thought of Foucault.

Panopticism

Panopticon, Jeremy Bentham [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

In Discipline and Punish (1975), Foucault wrote a great deal about the “disciplinary society” being a “panoptic” one, referring to Jeremy Bentham’s idea for a panoptic design for a prison. Section 3.3 (“History of the Prison”) of the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy’s entry on Foucault is a nice, concise explanation of Foucault’s discussion of panopticism and discipline. And here is a post that connects panopticism to social media, and starts to get to the concern I’m working towards here.

It’s not just a concern about possibly being observed at any given moment. Nor is it only that there could be a potential danger to this vis-à-vis power relations in one’s place of employment. It’s also that this situation of potentially being observed at any given moment can pressure one to change one’s own behaviour in order to bring it more in line with dominant norms. We police ourselves, rather than having to be policed. There doesn’t even have to be anyone watching for this to happen.

Now, this isn’t always necessarily bad. I agree with Alec Couros’s tweet, above, that knowing others might see my work would spur me to make it as good as possible. Plus, of course, if others saw it and commented, this could help me improve it even more.

But the potential downside is that one might be less likely to try radically new things, to experiment, to risk doing things that don’t fit with dominant views of how education is “done.” Clearly this isn’t true for everyone; there are people doing innovative things openly (e.g., many of the conspirators in ETMOOC)–though even then one usually has a community with its own norms that one is part of.

The issue would be prominent especially for those who don’t have tenured or otherwise semi-permanent positions–it’s often (though not always) in their best pragmatic interest to police themselves not to take too many risks if their work is open, though some risk-taking might be seen as positive.

So one reason some people might not be willing to be more open in their teaching and learning might be because of vulnerability. They could be vulnerable in the sense of not having a stable position, or in the sense of having a particular department or school climate that makes it such that opening their teaching could be dangerous to their position (because their colleagues may not agree with what they’re doing, e.g.).

I am fortunate in that neither of these situations applies to me, but that’s a bit of a luxury, and there are many people who don’t have it.

One more thing

I wonder if making my courses more open, in the sense of recording the sessions, would change how I conduct some of my class meetings. A fair number of them are unscripted, experimental forays into topics through (sometimes haphazard) discussion that may or may not come to a clear end point (usually not). I think of these as part of a work-in-progress, a long-term work in which I and the students are moving towards better understanding of certain issues, questions, arguments, texts. Or at least, different understanding that brings up fruitful, new ways of thinking about and approaching these things, showing further dimensions that were hidden before. This work-in-progress may last for a few weeks or months, a few years, or a lifetime. The courses, for me, are just a very small part of this process. In some ways I like that the class meetings are evanescent, short-lived; they aren’t final products in any sense and aren’t meant to be. I wouldn’t want anyone to watch one or two such meetings and get the sense that what I or anyone else says there represents anything more than a provisional test of a thought or argument. It will always change later.

Somehow, recording one’s course sessions seems to me to be making them more permanent, which goes against the way I think of the meetings. I want them to be memories only, things that change when you revisit them, just as the ideas do.

Of course, these issues exist with writing and publishing too–writing is never permanent, and one’s arguments can change radically over the course of a few years. But writing already seems more stable than a class discussion that takes place orally.

Conclusion?

I don’t have one. I just wanted to explore why I might have been reticent to be open, and why others might be. These thoughts on panopticism and sharing things publicly are anything but new, but they may be factors for some.

As with anything, there are benefits and drawbacks to being open in teaching and learning. I think the benefits, in my own personal situation, outweigh the risks of being open (as well as the concern about “permanency” noted above). But that may not be true for everyone, and it may for reasons other than a desire to keep one’s work to oneself, or out of a lack of confidence.