In three minutes, you will learn how to perfect your cup of coffee – just the way you like it.

To do this, we have to talk about chemistry!

Seven years ago, German food chemists researched how the bitterness of coffee changes depending on how long you roast the beans.

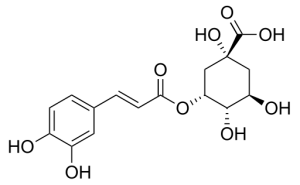

They confirmed what Trugo and Macrae found in 1984: the more you roast coffee beans, the more bitter the coffee tastes because organic compounds called chlorogenic acids are degrading.

Structure of one chlorogenic acid: 5-O-caffeoylquinic acid. Wikimedia Commons: Ed. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Neochlorogenic_acid.svg

Then, what makes this 2010 study different?

Well, these German scientists used evolved technology.

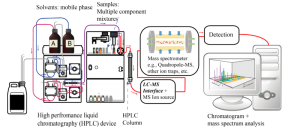

In 1984, those researchers used High Pressure Liquid Chromatography (HPLC), a technique that separates the components of coffee in a solvent. In 2010, however, the German researchers used the evolved form of HPLC: HPLC-MS/MS and HPLC UV/Vis. The combination of HPLC with mass spectrometry (MS, another analytical technique) enabled these researchers to figure out how much there is of each compound as you increase the roasting temperature.

An HPLC-MS Diagram. Wikimedia Commons: Daniel Norena-Caro. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Liquid_chromatography_tandem_Mass_spectrometry_diagram.png

With this advanced tool, they tracked the concentration of three classes of compounds:

- Caffeoylquinic acids (CQAs), a chlorogenic acid, gives the non-bitter taste;

- Monocaffeoyl quinides (MCQs), also a chlorogenic acid, gives a pleasant bitter taste;

- And oligomers (Os), a newly discovered class of compounds in coffee, gives a harsh bitter taste

And found that as roasting temperature increases from 190°C to the maximum 280°C, the concentration of CQAs decrease exponentially, MCQs increase then decrease, and Os increase exponentially. So, the presence of each compound is different at different roasting temperatures.

With this knowledge, you can personalize the bitter taste of your coffee.

For example, if you prefer a pleasant tasting brew, set your oven at 235°C and roast your coffee beans for less than 20 minutes. Watch as your beans change from green to brown and crack twice.

Then make your coffee as usual: grind the beans in a filter, then pour hot water through.

(By the way, why should you roast your coffee beans? It’s easy and tastes much better!)

And so for YOU who’s a keen coffee-drinker, I also note that water percolation or “pouring hot water through” the coffee beans makes a difference in how much of these compounds there are in the end as well! Not that much of a difference, but if you really want that perfect brew, look into this study in the Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry.

As for me, I don’t like bitterness anyway; so I’ll just stick to water.

-Ivy Wu

![By Takeaway (Own work) [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)], via Wikimedia Commons](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/e/ea/Turkish_strained_yogurt.jpg)