Although crops are immobile, they can feel, communicate and protect themselves in an unexpected way. They sense the stressful surroundings, then secretly warning each other without making physical contacts. Their words are produced from their tissues or the roots’ bacteria, then reach another plant through the air. They talk and react to harsh environments, protect themselves from plant pathogens and pests, and eventually adapt to the stresses.

With years of research, scientists have realized that the crops and their root microorganisms abound with natural volatile organic chemicals (VOC), which would be released under stressful conditions, and stimulate the plants to react accordingly to their environment. For example, the volatile chemical, methyl jasmonate, is released when tomatoes are exposed to insects or damaged. This chemical then triggers proteinase inhibitor in the undamaged tomatoes or their neighboring plants, which prevents the plants’ tissues from being digested.

Pic. 1. “face to face talk”, volatile chemicals flow from plants to plants. (Credit: Woolly Pocket)

Certain growth-promoting bacteria in roots space (rhizobacteria) can also sense the stressful environment, and they would contact the crops with the volatile chemicals, so that the behavior of plants can be regulated together by both rhizobacteria and the crop shoots, according to Dr. Ryu and his team’s study.

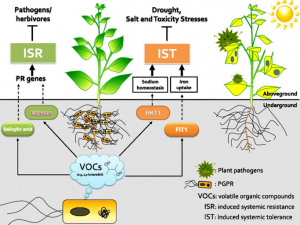

Pic. 2. Model of crop plants facing stressful conditions (PGPR= rhizobacteria, PR genes: Plant Pathogen genes) (Credit to Ryu et al, 2013)

They have found out that the rhizobacteria would trigger both ISR (induced systemic resistance) and IST (induced systemic tolerance) handling biotic and abiotic stresses separately. The rhizobacteria would produce salicylic acid and ethylene and trigger ISR for crops and prevent the pathogen’s infection. They can also regulate the sodium and iron uptake factors (HKT1 and FIT1), and the crop’s tissues would reduce the uptake level of these chemicals under IST.

It is also considered by Dr. Ryu’s team that the future fertilizers and/or pesticides can be developed from the bacterial-volatiles-plants relationship. They would apply certain water-soluble volatile chemicals, such as 2,3-butanediol, to make them more available for the rhizobacteria, which could then readily protect the plants. This chemical would be safe to animals and inexpensive (<$1/kg). But more research would be needed before such product becomes available in the markets.

Even without the potential application, it is still amazing to understand the crops’ languages and their lines of defense. Afterall, these wonderful creatures should be appreciated by their interesting behaviors more than just being food.