By Jamie Sinclair

| Name of the Artefact | Porcelain Figurine of Aryan Woman | “Soldatenlieder” Winterhilfswerk Booklet |

| Creator | Porzellanfabrik Schaubach Kunst | Nationalsozialistische Wolkswohlfahrt |

| Date | c. 1936 | 1933-1945 |

| Type | Figurine, porcelain. | Text and illustration on paper in ink. |

| Image |  |  |

| URL | https://collections.vhec.org/Detail/objects/2408 | https://collections.vhec.org/Detail/objects/6609 |

Fascist Façades: Charity, Superiority, and Volksgemeinschaft Under the Reich

Overview

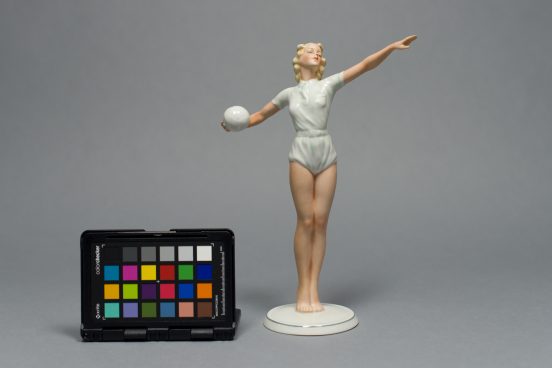

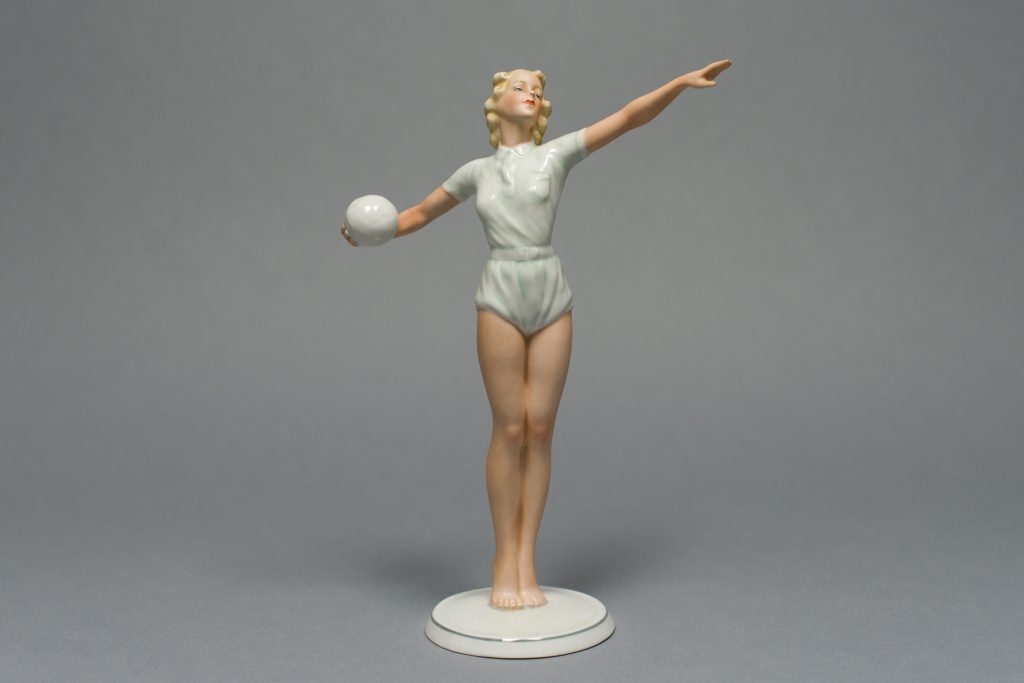

The first artefact is titled Porcelain Figurine of Aryan Woman, which was manufactured by Porzellanfabrik Schaubach Kunst, a porcelain factory in Germany. This figure falls under the Nazism and propaganda, as well as sports and recreation genres. It is likely to have been created around 1936 in preparation for the Berlin Olympic Games as an example of the archetypal woman under the Reich.

The second artefact is the “Soldatenlieder” Winterhilfswerk Booklet, (Winter Relief of the German People) which was published by the Nationalsozialistische Volkswohlfahrt (National Socialist People’s Welfare, henceforth NSV) in Germany. It falls under the Nazism and propaganda, as well as publications and ephemera genres. This German-language paper booklet was in print from 1933-1945, with the intent of acquiring continual donations for the NSV and distributing them to those in need.

Meaning

The Porcelain Figurine of Aryan Woman can be dated within the year 1936, during which the Winter Olympics took place in Berlin. It is likely that the production of such items was particularly lucrative, as they would have appealed to both the rising admiration of the Nazi Party (byname of National Socialist German Workers’ Party NSDAP) and the sense of nationalism that often accompanies sporting events such as the Olympics, two aspects of German society which would have been at the forefront of public consciousness at the time. The Porcelain Figurine of Aryan Woman is a collector’s item which was produced by Porzellanfabrik Schaubach Kunst (Porcelain Factory Schaubach Kunst), perhaps with the intention of reflecting these two popular topics in order to gain mass appeal. Nationalism is often reinforced through sporting events such as the Olympics because they “ask us to identify with…our national team” (Wade 81), which allows the average citizen to develop a sense of community and cultural identity. Wade further posits that this sense of national identity requires “us to believe in a series of fictions” (80) which support some political agenda or ideology that places the nation and its people above all others. It is no surprise, then, that such memorabilia—i.e. objects which reflected a glorified, fictionalized image of the ideal German citizen and evoked this aforementioned national pride—were created.

The second artefact was created by the Nationalsozialistische Volkswohlfahrt (NSV), a welfare organization whose stated goal was to provide aid to those in need under the Reich. The Winterhilfswerk (WHW) was one of its charity initiatives “from [which] its annual collection campaigns placed considerable [amounts] of money and…consumer goods at the disposal of party-sponsored welfare distribution” (Unger 134). The “Soldatenlieder” Winterhilfswerk Booklet is an example of propaganda given as a token of gratitude after a donation, though these donations were directed only toward those who qualified according to Nazi ideology, and this was true for virtually all such altruistic exploits (not just those directly associated with the WHW). For example, young female recruits were sent to the East where many “cared for and educated ethnic German refugees who streamed from Romania and Ukraine into…Poland” (Lower 35). But, of course, such charitable acts came at the cost of those deemed unworthy of altruism or even basic human rights—those same cared-for refugees were housed “where the occupying German force had brutally ejected Poles from their homes, stealing their property along with their livestock and personal possessions” (Lower 35). The WHW itself was established in the winter of 1933 by Joseph Goebbels, largely as a way of stirring up a sense of collective responsibility, after which it became a yearly event (Unger 136). This Winterhilfswerk Booklet is one of many items a donor could have received after making a donation.

Symbolism

The porcelain figure encapsulates the perfect woman as imagined by Nazi ideology: blonde, blue-eyed, and therefore easily categorizable as Aryan. Her stance is depicted as strong and her figure immaculate, emphasizing the importance of the able—rather than disabled—body, i.e. one free of deformity. The demonization of the disabled body stems from the perspective of “Social Darwinism and its idea of a threatening degeneration” (Bengtsson 421), which became the driving force behind the Nazi Euthanasia Program, known as Aktion T4. Because she is a symbol of racial—and therefore moral—purity, her athletic ensemble, the ball she holds, and even the platform beneath her feet are pure white. Hence, morality and fitness are linked in this way too; to be free of physical deformities is to be free of moral ones as well. According to Lower, “Nazi socialization…encouraged the gaze at the inferior as affirmation of one’s own superiority” (41), with the “inferior” being those who do not conform to the standards of perfection.

The figurine also represents the ideal wife and mother. Along with the athletic physique, the distinctly Nordic features of the figurine would have been desirable for future generations of the Aryan race. The figurine as sexual propaganda would have been particularly appealing for the men of the SS, whose potential wives required “extensive documentation certifying Aryan ancestry…, ideological loyalty, physical fitness, acceptable racial features (height, weight, hair color, nose shape, head measurements, profile), and fertility” (Lower 63). As such, the better her outcomes were on these measures, the more likely their marriage would be approved by Heinrich Himmler, who was in charge of these affairs at the time. The importance of cultivating future generations of immaculate Aryan children largely depended upon the association between physical fitness and fertility—i.e. a woman’s fertility was assumed to be inferable from her physical attributes.

As we can see, these standards of physical perfection and their inferences are largely visual; that is, to even be misperceived as being part of an undesirable group could subject you to that group’s fate. This assessment of inferiority is so surface-level that any slight misperception could condemn those who, had they not been opponents of the Nazis, would have otherwise fit into this exclusively Aryan world. For example, Käthe Anders writes that while she was in the Uckermark Youth Custody Camp she was falsely assumed to be Jewish by an SS doctor and was consequently subjected to sexual abuse and further humiliation. Anders notes: “I had such dark eyebrows and my nose is a bit big,”[1] phenotypic characteristics which, according to Nazi doctrine, are indicative of Jewish heritage and therefore may have led the doctor to his false conclusion. Further, the fit, athletic, able body is not just an ideal on the individual level; rather, this ideal also represents the German people as a whole as healthy, strong, and proud—the epitome of the Übermensch (the superior man) As such, the conceptualization of the German people as such a powerful collective is embodied by the visual image of the ideal man or, in this case, woman. In other words, this visual image of the individual serves as a symbol of the collective.

This glorification of collectivism and strong sense of civic duty (Volksgemeinschaft , or a national community) was also central to the WHW, as it “was designed to impress the concept of national solidarity upon the people by eliciting a contribution from every German citizen” (Unger 136). Once this contribution was elicited, its significance of was reiterated and reinforced via a token of thanks —i.e. some work of propaganda—such as the “Soldatenlieder” Winterhilfswerk Booklet. This token was, in turn, effectively evidence of one’s contribution to the greater cause, ensuring a better future for all German people.

According to Mazower, the generosity associated with Volksgemeinschaft made it “necessary to take the life of others, expropriating their goods and redistributing them…[to] those inside the nation” (78), but the act of stealing need not be limited to material things—the demonization of certain groups effectively robs them of their place in society. To make a donation to the WHW would have been to essentially exclude all other “non-German” groups of individuals from material as well as social charity. In other words, those belonging to these excluded groups (the majority of whom would have been placed in ghettos and Nazi camps with appalling conditions) would be deemed undeserving of the sympathies of the Übermenschen.

It is in this way that the “Soldatenlieder” Winterhilfswerk Booklet functions as both evidence of the donor’s loyalty to the Nazi Party and incentive to donate again. Nazi propaganda leant heavily into this sense of community, particularly in its use of terms relating to sacrifice, righteousness, the strengthening of social bonds, and moral purity (Yourman 150). The “Soldatenlieder” Winterhilfwerk Booklet contains German soldiers’ songs which would have been well known to those at the time. The imagery of the soldier, too, reflects the fixation on the noble sacrifice as an integral part of Nazi ideology. Further, this emphasis on the glory of the collective fuels the desire to rectify the misfortunes of the true German people. However, the WHW does not represent altruism for the sake of altruism; rather, it can be viewed as a series of deliberate calls-to-action meant to stir up feelings of fervent patriotism and feed the donor more sinister propaganda in the form of these tokens of gratitude.

[1] Translation of Käthe Anders, “Nie gelebt,” by Uma Kumar and William Orr, University of British Columbia, 2019.

Aftermath

The type of woman depicted in this figurine has become somewhat infamous as a visual symbol of the future imagined by Nazi ideology. This ideal woman was characterized as racially pure, in perfect health, and a devoted wife and mother, yet even this devotion to the family would have ultimately been in service of the Reich. As Lower points out, “women mimicked men doing the dirty work…that was necessary to the future existence of the Reich—because they were racial equals” (62), which was reflected in their significant participation in Nazi operations.

But at present, it is also apparent that, while egalitarian in some respects, the relatively large array of career opportunities for women was primarily due to the fact that there was an increasing demand for labour and not enough men to meet it, as well as the fact that women could be underpaid (Lower 61). Women played a much more important role than was previously assumed and while their “contribution to the Nazi system was enormous…the mother remained the heroine of the German race” (Lower 61), placing the emphasis still on the perfect woman as a representation of the ideal Aryan mate with whom the fate of the German people could be entrusted. In the modern world, she represents an outdated idea of womanhood in which her value is determined by her ability to contribute to the nation, either as a source of labour or as a bearer of Aryan children, the latter arguably the more appealing and celebrated position of the two. This figurine in particular reads more as a representation of the latter due to the emphasis on physical perfection which, as previously mentioned, not only qualifies her as Aryan, but also would have been seen as indicative of fertility and her ability to contribute to the nation in that regard. It is in this way that she can be retrospectively viewed as a manifestation of the sinister objective which was central to Nazi ideology, i.e. a glimpse into a future in which the world has been purged of practically all non-Aryans and all that remains are the master race, their descendants, and the slaves who do their bidding.

While at the time the booklet might have been a symbol of charity and altruism, its meaning is coloured by the knowledge that—at the exact same time of its distribution—the Nazis were implementing inhumane transportation procedures and placing people in ghettos and camps with horrifying conditions. While the WHW pushed their agenda of improving the quality of life for the “true” German people, individuals such as Käthe Anders were starving and/or becoming ill from what little food they were given. She speaks of the physical and mental toll of her experiences at Uckermark after months upon months of hard labour, starvation, torture, and humiliation, saying: “In the end, when you are already completely thin and feeble, you don’t have any more energy… [nor] any thoughts of defending yourself.”[1] Jean Améry, as a member of a resistance movement, was imprisoned and brutally tortured. Recalling a particular experience he endured during his imprisonment, Améry describes “[t]he Flemish SS-man Wajs, who—inspired by his German masters—beat me on the head with a shovel handle whenever I didn’t work fast enough” (70).

At present, it is clear that these organized charitable endeavours belie the maltreatment and execution of those who were condemned for being racially impure, politically opposed, physically disabled, mentally ill, homosexual, and so forth. The “Soldatenlieder” Winterhilfswerk Booklet might have been promoted as a symbol of kindness and concern for the wellbeing of others at the time, but in the contemporary world, its meaning has changed drastically for one obvious reason: these charitable exploits were implemented by the same organization which systematically imprisoned, tortured, and murdered millions of men, women, and children.

[1] Translation of Käthe Anders, “Nie gelebt,” by Uma Kumar and William Orr, University of British Columbia, 2019.

Works Cited

Améry, Jean. At the Mind’s Limits: Contemplations by a Survivor on Auschwitz and its Realities. 1966. Translated by Sidney Rosenfeld and Stella P. Rosenfeld, Bloomington, Indiana University Press, 1980.

Anders, Käthe. “Nie gelebt.” Ich geb Dir einen Mantel, daß Du ihn noch in Freiheit tragen kannst, edited by Karin Berger, Promedia, 1987, pp. 97-106.

Bengtsson, Staffan. “The nation’s body: disability and deviance in the writings of Adolf Hitler.” Disability & Society, vol. 33, no. 3, 2018, pp. 416–432, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/09687599.2018.1423955.

Lower, Wendy. Hitler’s Furies: German Women in the Nazi Killing Fields. New York City, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2013.

Mazower, Mark. Dark Continent: Europe’s Twentieth Century. New York City, Vintage Books, 1998.

Porcelain figurine of Aryan woman, circa 1936. Vancouver Holocaust Education Centre, https://collections.vhec.org/Detail/objects/2408

“Soldatenlieder” Winterhilfswerk booklet, 1933-1945. Vancouver Holocaust Education Centre, https://collections.vhec.org/Detail/objects/6609

Unger, Aryeh L. “Propaganda and Welfare in Nazi Germany.” Journal of Social History, vol. 4, no. 2, 1970, pp. 125-140, www.jstor.org/stable/3786221.

Wade, Lisa. “Banal Nationalism.” Contexts: Understanding People in Their Social Worlds, vol. 10, no. 3, 2011, pp. 80-81, http://ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/login?url=https://search-proquest-com.ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/docview/1081455457?accountid=14656.

Yourman, Julius. “Propaganda Techniques Within Nazi Germany.” The Journal of Educational Sociology, vol. 13, no. 3, 1939, pp. 148-163, www.jstor.org/stable/2262307.

Comments by Amanda Grey