First Peoples Principles of Learning

First Peoples Principles of Learning

In response to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada: Calls to Action, I am committed to a pedagogy of practice that acknowledges the harm caused to Indigenous Peoples in Canada, and the opportunity First Peoples Principles of Learning provides to enrich the educational paradigm.

I am a white settler living in the City of Vancouver, on the traditional territories of three Local First Nations: the Musqueam, Squamish, and Tsleil-Waututh. My auntie was apart of the sixties scoop and, and my cousin (same age as myself) continues to experience the legacy and harm of colonization. My mom’s family emigrated from Holland and thought they were doing “good” by adopting a First Nation child, even though there were already six children in the home. My dad’s family links back to eastern Canada and were original colonizers. My grandma has shown me a photo of my great-great-great-grandmother who was First Nations. My aim is to cultivate two-eyed-seeing and, similarly teaching through a lens of hybrid-epistemologies. I aim to hold the complex contrasts and beauties of both Indigenous teachings, histories, while by the exact same breath, holding space for western knowledge. Not sure which one is the inhale or exhale, but they both flow through my lungs like a crisp Spring morning. I aim to ask my students: learn to look again, with your eyes at the very edge of what is visible… You must learn to look at the world twice if you wish to see all that there is to see (Green Teacher).

Montana/ Cheif Rock, In preparation of ceremony (Sundance)

With that said, I believe that Indigenous knowledge functions as a tool of inquiry both in the classroom, but also regarding our very own identity and how it can become a part of the fabric of connecting to place, community, and chiefly to nature.

In the article, The First Principles of Learning in Teaching Education: Responding to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s Calls to Action” Amy Parent, SFU scholar states: “our teachings from Indigenous scholars and knowledge holders suggest that relationality is a key understanding in Indigenous worldviews and can support reconciliation” (p. 41). Reconciliation is dive, it is messy, honest, and functions in ‘risk’. It is also salient to highlight the importance of Indigenous ceremony as a powerful entry point of learning. I have attended a sweat lodge on the Squamish Territory in 2009, and was on the “Blood Indians” or Kainai Nation for a traditional Sundance located in Alberta/Montana, on Kainai Reserve. It was one of the most powerful educational experiences and is my internal spark for place-based experiential learning.

How did I blend First Peoples Learning Principles into my teaching?

Principle 1: Learning ultimately supports the well-being of the self, the family, the community, the land, the spirits, and the ancestors.

Teaching a place-based lesson on two-eyed seeing at Central Park in Burnaby. October 19, 2020.

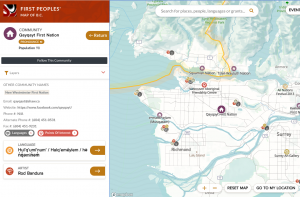

A) What is the traditional land or territory of First People at Central Park? Central Park is on the land of the Quyqayt First Nation. Burnaby is located on the ancestral and unceded homelands of the hən̓q̓əmin̓əm̓ [mp3 audio file] and Sḵwx̱wú7mesh speaking peoples.

First Peoples’ Map of BC

Students incorporated Quyqayt First Nation and their language Hul’q’uml’num into their vocab books. I asked the students why might knowing these words be apart of reconciliation? (https://maps.fpcc.ca/content/qayqayt-first-nation)

B) Connection to story and place. Once we arrived at the park, standing in a circle, I shared: The traditional territories of a family or clan group within these broader groups. Traditional territories referred to in this context may not be the same as those lands under legal or political considerations such as land claims. Boundaries between territories are not precise.

One definition of the traditional territory is “the area that the local Indigenous people have occupied since Time Immemorial.” Introduce students to the term time immemorial: since creation; before recorded history.

“Time immemorial” expresses the depth of time that Indigenous people have lived sustainably on their territories. It is time beyond memory.

- Ask students what their earliest memories are

- What types of topics or activities make up their early memories?

- Ask what they know about their families before they were born.

- Ask how they came to know about their family history. (e.g. family stories, photo albums, home videos, books).

- How far back in time do our family stories go?

C) Land-based learning

- How has biodiversity changed here over time? What used to be there? What is here now?

- Can we imagine what used to be here? Can you imagine what was here?

The story of this place: Let students know that the land we’re standing on is stolen. That all of the trees around us were harvested by white men and sold. That this land has been here for millions of years, for hundreds of generations. That this spot only became a public park in 1891, a year after it was logged (logged in 1890). Prior to it, throughout the 1860’s the Royal Navy used the land to build ships. The park was named to honour Mrs. Sarah Christine Oppenheim (the wife of the Vancouver’s second mayor) she was born in New York City. The park has two man-made lakes and streams. Both lakes are habitat to Canada geese, mallards and waterflowel. The upper lake is home to crawfish and minnows. The lower lake has a school of brown bullhead, a fish in the catfish order.

The story of this place: Let students know that the land we’re standing on is stolen. That all of the trees around us were harvested by white men and sold. That this land has been here for millions of years, for hundreds of generations. That this spot only became a public park in 1891, a year after it was logged (logged in 1890). Prior to it, throughout the 1860’s the Royal Navy used the land to build ships. The park was named to honour Mrs. Sarah Christine Oppenheim (the wife of the Vancouver’s second mayor) she was born in New York City. The park has two man-made lakes and streams. Both lakes are habitat to Canada geese, mallards and waterflowel. The upper lake is home to crawfish and minnows. The lower lake has a school of brown bullhead, a fish in the catfish order.

This park has a variety of birds: downy woodpeckers, towhee, American Robins, Sparrows, finches, and crows. It is home to the Douglas squirrels and northern coyotes.

Invasive species: eastern gray squirrel and snakehead fish (meaning that when settlers came, they also brought plants from different countries- both intentionally and by accident, these plants are messing up the balance of the forest—they were never meant to live in this ecosystem.

I walked around with the map of what Central Park looked like prior to colonization. I asked students to identify what they saw in the image.

D) Observation & Two eyed-seeing. Students took 4 m x 4m string and found a patch of land. Students observed the piece of land in silence for ten minutes. Just observing. Afterward, given an additional ten minutes, they sketched what they observed in nature. I asked them to consider:

Central Park, October 19, 2020. Grade 6 student sketching

“First you must bring your eyes together in front so you can see each droplet of rain on the grass, so you can see the smoke rising from an anthill in the sunshine… But you must learn to look again, with your eyes at the very edge of what is visible… You must learn to look at the world twice if you wish to see all that there is to see.” ( https://greenteacher.com/two-eyed-seeing/)

Students observed, sketched, and took a photo of their square of nature. Next class they will use western knowledge to search the names of the plants and, what plants were helpful to the First Nation (Qayqayt), and or any identified medicine. Next week we will come back to the same spot and apply our new layer of knowledge.

E) Healing and Reconciliation. I asked the students as we headed out of the park through the Central Park central entrance, exploring signage outlining the colonial history—why there was no mention of the Qayqayt people? If this is their land, then why is there no acknowledgment of it? One of the students blurted out: “It is kind of like showing a piece of art that isn’t yours and taking credit for it when you didn’t even create it.”

*What does reconciliation look like in this place? How can we cultivate it here? What is missing?

———————————————————————————————————————————————-

Principle 2: Learning recognizes the role of Indigenous knowledge.

Grade 6 math lesson, understanding hundred-thousands

Teaching grade 6 math from the text Math Power, I was disappointed by how the textbook described “aboriginals” and used their population for a math question, without providing meaningful fodder. It felt exploitive rather an than opportunity for meaningful mathematical learning. There was a missing piece and opportunity to include Indigenous knowledge. I made a new and more inclusive math page, augmenting the textbook to help students round to the nearest hundred-thousand. I also asked students that we know that smallpox killed 90% of Indigenous Peoples in Canada, what might the total population of Indigenous Peoples in Canada reflect. In addition, I showed them a video about how we describe Indigenous peoples when we discuss them in this math lesson. Before I handed out the math sheet I showed them a CBC Kids video titled: What is Indigenous, Explained:

After discussing how we describe Indigenous People in Canada, by using Metis, First Nation, and Inuit. We added the words to our vocab book and had a class discussion regarding why using the most descriptive words are necessary when discussing Indigenous Peoples in Canada.

We worked through the more inclusive math worksheet, titled Estimating Population. This document was also foundational for us, when we moved to Social Studies the next day, discussing the number of COVID 19 cases in each province. We discovered that there are zero COVID cases in Nunavut. We as a class were able to pull on previous knowledge regarding the per cent of Indigenous People (we also assumed, and used accurate language: Inuit people) who live in this place and have a deeper understanding of the Social Studies materials.

Recreation of Math Power 6, Estimating Populations

Collective and Collaborative Land Acknowledgment, November 4th, 2020

Today we trekked out to the rain to Central Park, Burnaby to identify native plants. We used Pacific Northwest Plant Knowledge Cards to explore the forest. Each card describes the plant name in both Hul’q’umi’num’ but also in English.

Each plant card uses both the English plant name and Hul’q’umi’num’ language

Pacific Northwest Plant Knowledge cards

Together in a circle, we as a group discussed Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK). Students led the land acknowledgment. Students shared about the land we stood on (Qayqat land), the Qayqat First Nation speak the language Hul’q’umi’num, and how the Qayqat People have lived on this land since time and memorial.

In a circle, students were encouraged to share what traditional knowledge has been shared in their families. What traditions have been passed to them? After a student shared their traditional knowledge they would take the string and through it to another student to share, until a web was created.

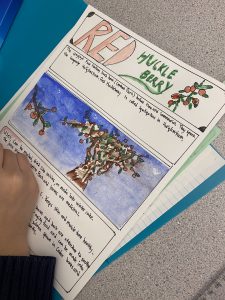

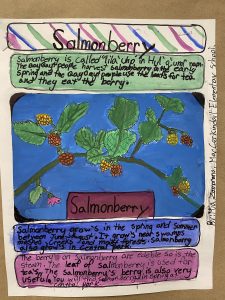

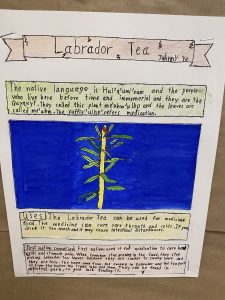

Students’ final science project was to create a native plant card. These are a sample of some of their finished projects.

A student creates their card

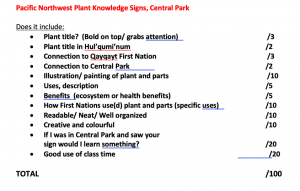

Assessment

The final project was co-designed with the students. They had the idea of indigenizing signage in Central Park. We made new signage that provided information about the plants that grew in Central Park. The items included in the assessment were pulled from ideas from the students—when I asked them what the signage should include. I created an exemplar of what one card could look like, including all the items in the co-created criteria. I provided students with creative freedom, using watercolor, fine liners, and card stock. Seen below are a few examples of their final creation!