Professional

Incorporating place-based/ land-based, environmental education, environmental sustainability, and Indigenous ways of knowing into future teaching practice

Margaret McKeon, outdoor educator at the Western School District in Corner Brook, Newfoundland writes in her 2012 article Two-Eyed Seeing into Environmental Education: Revealing its “Natural” Readiness to Indigenize shares the concept of a “touch-smell-listen session” to the environmental education program. This includes asking students to touch the ground, and ask: “What is this? Moss? Ground? [Folks] it’s the Earth. Aboriginal peoples call this Mother Earth. What pops in your mind when you say the word mother? What does your mom do for you? What does Mother Earth do for us? [further sharing] the importance of taking only what you need, and about knowing how to spend time on the land respectfully” (p. 134).

McKeon closes the article with these words: “Environmental Education is about re-storying our lives, the land, and our relationship to it. Through Two-Eyed Seeing it can also become focused on interconnection: between peoples, between ways of thought, between human beings and the natural world. It is a celebration of the magic and beauty of this world. An indigenized environmental education speaks for the education that tells a new, holistic creation story It is an education that includes the interconnection of interactions with the natural world and all peoples that is based on love and care-taking rather than fear or ownership.” (p. 143)

My professional goal is to teach environmental education through story and place. Starting with the place that we are now, connecting with it and through dialogue and inquiry find a way to connect it to a wider web of place and meaning.

Land-Based vs. Place-Based Education

Mandala found on a walk on a trail in Pacific Spirit Park, June 2020

Place-based education is not enough to “promote decolonizing goals”… and “consider Indigenous agency and resistance tied to Indigenous cosmologies.” Scholar Dolroes Calderon says, “here we can see that a land education approach requires that students understand themselves fully within the context of place. This means not only understanding themselves in the present and future of the place but also the past and how all three shapes who they are today and where they dwell.” Place-based learning is a modality of education I aim to incorporate. For example, taking children on silent walks through the forest or walking around the city with the intention of curiosity-creating a hypothesis of what is around them. That said, I aim to pose questions like, what was here before you were born? Or, what do you think will be here in ten years? Who land is this? What happened here before we arrived today?

Teaching goals

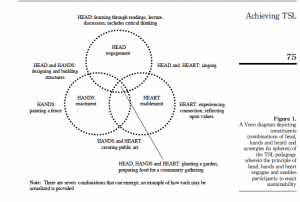

Sipos, Y., Battisti, B., & Grimm, K. (2008). Achieving Transformative Sustainability Learning: Engaging Head, Hands and Heart. International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education, 9(1), 68-86. doi:10.1108/14676370810842193

Being in nature provides the opportunity to utilize SFU Professional Program Goals of Teaching. Goal 8: The development of the ability to create opportunities for learning- The access and engage students’ ability to think and learn through their minds, bodies, and hearts. Being outside in nature is an opportunity to use place-based and land-based education as a tool for students to use their hands (experiential education), hearts (personal connection) and, heads (critically thinking and applying knowledge) (Sipos, Battisti & Grimm, 2008, p.72). A salient example of applying all three modalities: hands, head, and heart, as highlighted in the article Achieving Transformative Sustainability Learning: Engaging Head, Hands and Heart (2008) is a child working in the garden outside. The child is “planting a garden; preparing food for a community gathering” (Sipos, Battisti & Grimm, 2008, p.75) as students’ have the opportunity to “think and learn through their minds, bodies, and hearts” (Professional Development Program, SFU). The head portion evokes the idea of teaching the facts about the environment, and the heart encompassing the feeling of harmony and, the hands utilized with an opportunity to connect to the senses. The senses could include smelling flowers, touching the bark of old-growth cedar, or smelling the ocean breeze.

We need a new modality of education that provides students with the opportunity of applying their hands, head, and heart as outlined as a teaching goal by Simon Fraser University and Indigenous Peoples.

Teaching Resources

Curriculum Guide, Project Wild

Natural Curiosity 2nd Edition: A Resource for Educators

Influences on Professional Paradigm

Calderon, D. (2014). Speaking back to manifest destinies: A land education-based approach to critical curriculum inquiry. Environmental Education Research: Land Education: Indigenous, Postcolonial, and Decolonizing Perspectives on Place and Environmental Education Research, 20(1), 24-36. doi:10.1080/13504622.2013.865114

McKeon, M. (2012). Two-Eyed Seeing into Environmental Education: Revealing its “Natural” Readiness to Indigenize. Canadian Journal for Environmental Education, 131-147.

Professional Development Program, SFU. (n.d.). Retrieved June 14, 2020, from https://www.sfu.ca/education/teachersed/programs/pdp/goals/10-goals.html