Nature

GETTING TO HOME: THE PATH OF FINDING NATURE

“When we see land as a community to which we belong, we may begin to use it with love and respect”– Aldo Leopold

Getting to Home: The Path of Finding Nature

“When we see land as a community to which we belong, we may begin to use it with love and respect”– Aldo Leopold

I found home in a stream. A tadpole bearing stream where I rested my heart, exploring the far corners of my imagination. During my parents’ divorce, at the age of seven, I found refuge and a sense of escapism, in the dewy, mossy and lush acreages of cedars, pines, Douglas firs and raspberry bushes, extending beyond the green grass of my middle-class, suburban home. I was free to independently explore the wilderness of the lush west coast rainforest. I carried a bucket full of tangled sorrow with me out into the forest, and often returned home after hours of play, with a terrarium of flora and fauna. Seldom a frog, if I was really lucky! The forest soothed the edges of my parents’ divorce, including the death of a close family member. It held me.

When I visited my childhood house as an adult, I froze. The acres of forest had been chewed and spat out into a monoculture of homogeneous houses. I spent some time sitting in the car, enthralled by the sprawl of dismay– ruminating over the impact of the unfamiliar landscape and its curious topography. It jolted me. My tree fort which had stood erect just beyond the property line, had vanished into further extensions of suburban grass.

My first connection and deep appreciation of nature was in that forest. When I moved to Toronto, I was dumbfounded by the amount of people who basked their weekends away in cottage country. It did not take long to discover that quintessential Ontario, could only be found in the beauty of the Muskoka’s. Or so it is branded. Torontoian’s drive three to four hours in seven lanes of traffic, one direction, to retreat in nature. This is the norm. Toronto, nestled along Lake Ontario, is a beautiful and expansive lake, lined with birch trees, and interestingly the most dynamic bird ecosystem in North America- The Lesley Spit. A tourist might not be familiar with the cormorants and exotic bird species that flock to this particular region but will for certain have heard of Niagara Falls. However, the beauty of the urban lake, doesn’t persuade recreational use, as it is often off-limits due to outdated water storm-pipes, which often discharges raw sewage directly into the waterfront. The only people found enjoying Lake Ontario are new immigrant families and those who do not have the economic and social capital to retreat to Muskoka. My own family is guilty of this unconscious practise. My dad bought a family cabin past Hope, B.C., and it has become a regular family tradition to travel to the cabin for family events. My dad calls it his retreat into nature, ironically he lives in a townhouse along the seawall in False Creek, Vancouver, with a view of the ocean.

As someone who is deeply concerned about climate change– I am alarmed by the license we allow normalizing a lifestyle that includes commuting to nature, while burning extensive amounts of CO2 throughout the process. Reflecting on the day I visited my childhood home; I did not have the mental and emotional resources to describe why I was heartbroken. Why had the forest of my past meant so much to me? I did not know how to grieve for my seven-year-old self.

Nature matters. Children need nature to retreat into. Sanctuary. Forests are canvases for creative minds, and expressive hearts. Every child should have access to nature, uninhibited by organized play or tasks. They should have time to utilize their senses, create their own games, their own world distinct from the hardness of this one. As an adult, I tap into this knowledge, a somewhat unconscious strategy to find inner peace- I retreat into nature. I know myself well enough, that after spending twenty minutes outside, walking with my dog that I feel calmer and more grounded.

Being in nature is only problematic when there becomes a need to find nature– the need for an exotic experience. I believe that the concept of nature has become a socially constructed experience. The desirable scared forest has become a place only accessible by white, able bodied folks who have the financial means to own their own private car. Nature is a commodity. Accessed by those who can afford a patch, connected by corridors of fast motorways.

I believe that children who grow up in nature, who spend time in nature, who create nostalgic memories of creative play with loved ones, appreciate nature as adults. To this point, appreciation really needs to be described as a vessel of sacred connection. Connection to the power of wild, magical, free and creative energy that only our hearts can begin to quantify. Science verifies that spending time in nature can boost our moods, creates antibodies, and is overall good for our health and well-being.

Where is nature? Nature isn’t a destination. It is not a campsite that you reserved two months in advance. It is not a vacation, you had to book time off from work and it is definitively not an all-inclusive in Mexico. Nature is not somewhere to get to. Nature is not out there. Nature is not the Redwoods. It is not in Haida Gwaii or Garibaldi and for those very misinformed, it is definitely not one of the thousand switchbacks along the Grouse Grind’s vertical tourist tower. Nature is not getting into your car and driving to Stanley Park, searching for parking among the other eager nature seekers. It is not traveling on an airplane to a country with a more temperate climate, to admire rare sensational topographic scapes of managed wildlife. Shockingly, it cannot even be purchased at Mountain Equipment Co-op! These examples are the social construction of nature, it is the commodification of nature where flora and fauna are packaged, exclusive and only for certain portion of society. Those whom are able to access its exotic treasures.

What is nature? No other human sums it up like William Cronon (1995). An academic and forward thinker that inspired my work throughout my undergrad and masters. In his article The Trouble with Wilderness or; Getting Back to the Wrong Nature, he so delicately states, “Wilderness gets us into trouble only if we imagine that this experience of wonder and otherness is limited to the remote corners of the planet, or that it somehow depends on pristine landscapes we ourselves do not inhabit.” He goes on to stay, “nothing could be more misleading.” Cronon’s words, always poetic, alludes to the fact that nature is not out there, it is right in front of us. Nature is in our cities. It is the moss that grows in the cracks of the sidewalk. It is the vines that consume the heritage home on the corner of your street. Nature is the raccoon the breaks into your compost at night, leaving you a 7:00am surprise. Nature is the rain drops. It is the sound and smell of the weight of the drops. It is the tree in your front yard and the green overflow of ‘weeds’ in your back alleyway. Nature is the bees. It is the tidal zone that is only a twenty-minute walk from your condo. Nature is the box of herbs growing on your windowsill. Nature is everywhere! It is a part of us, and worth protecting.

We have forgotten to see the nature around us. It has become the backdrop of our lives. Blended in and lost from days of endless dew and time lapsed while running for a late bus. Cronon says, “our challenge is to stop thinking of such things according to a set of bipolar moral scales in which the human and the non-human, the unnatural and the natural, the fallen and the unfallen, serve as our conceptual map for understanding and valuing the world. Instead, we need to embrace the full continuum of a natural landscape that is also cultural, in which the city, the suburb, the pastoral, and the wild each has its proper place, which we permit ourselves to celebrate without needlessly denigrating the others. We need to hono[u]r the Other within the Other next door as much as we do exotic Other that lives far away– a lesson that applies as much to people as it does to (other) natural things. In particular, we need to discover a common middle ground in which all of these things, from the city to the wilderness, can somehow be encompassed in the word “home.”

The stream in the back of my childhood house, was my home. It was my sanctuary. Every child has the right to access nature. It was my first true love.

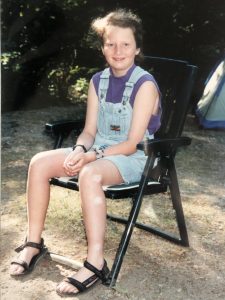

The photo above my childhood backyard space and me at the age of nine