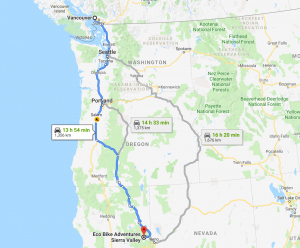

In third year, my life became a feverish balancing act. It was the year I took up 6+3 first and second term courses while trying my hand at leadership on the SUBC drivetrain team. In September, I had moved to downtown Vancouver with friends after living with family for years in Richmond. It was an exciting transition that would kickstart a much more social life – something I’d craved for a while.

I remember brimming with energy those first few months. On SUBC, I had assembled a strong team ready to tackle the design of our submarine gearbox. Classes kept me engaged and eager to learn more. I even found time to enjoy the downtown high life with friends and roommates.

I flew through first semester, eventually hitting second. That’s when my schedule changed dramatically as my SUBC commitment grew. My Saturdays became fulltime SUBC work sessions, pushing homework to Sundays. Soon enough, I was working 7 days a week, often more than 8 hours a day consecutively. Fewer were the weekends I found time for leisure.

“Paltry,” you might be thinking, “that’s Mech bread and butter.” And I would have agreed with you. My meager 12 credit course load in second semester signaled no excuse to compromise working hard. After all, now I had too much free time on my hands! In no universe could I allow myself to perform poorly. As the semester progressed, this mindset became increasingly sabotaging.

Before I knew it: burnout! It’s a condition I didn’t entirely understand or even really believe. After all, stress fuels productivity—until it doesn’t. Reality set in when I began to notice growing frustration over the simplest tasks. Exhaustion seemed to kick in unusually quickly. Ignoring these telltale symptoms, I fell into a cycle of downplaying burnout, reminding myself that I’d survived MECH 2 during COVID, so obviously I could survive any onslaught.

But despite my rationalization, every bit of work continued to feel like a step in some gargantuan supertask. I thought that my effort and energy could only be bounded by ambition, but much like an apparently infinite series, I discovered they needed to converge to a finite sum.

Even precious downtime with friends seemed to feel like a burden. An ever-present mental checklist fogged my brain, pulling me from enjoying life in the moment. I was chronically anxious that I had forgotten some crucial SUBC task or course assignment. My confidence waned and grades declined. I fell ill with a prolonged seasonal cold and experienced constant back pain – all the while beating myself up over being so “weak.” My stubborn work ethic turned exhaustion into a cruel measure of self-worth.

As a workaholic, the line between dedication and self-neglect blurs as perfectionism clashes with the need for rest. In my experience, this made burnout a nearly imperceptible threat. When your commitments start feeling like they’re getting to you, ask yourself:

- Have I been feeling exhausted recently?

- Do I feel ineffective at the work I’m doing?

- Do I feel distant from my work or a loss of interest in it?

- Am I feeling easily irritable?

If your answer is yes to one or more of these, I encourage you to critically reflect on your workload, schedule, and mental wellbeing. According to Mayo Clinic, among the biggest signs of burnout are exhaustion, reduced efficacy, depersonalization, and cynicism. This can make it very challenging to honestly assess yourself. Verbalizing my frustration with a supportive friend was a great way to get an outsider’s perspective on my situation. The UBC Student Services website also offers a comprehensive guide to managing stress responses, emphasizing support-seeking, relaxation activities, exercise, sleep, and mindfulness practice. These tools, while not guaranteed cure-alls, can help you think about how best to manage your response to stress. In my experience, starting with the simple admission that I even had burnout was a great way to dissolve the ego that kept me from addressing it.

Why? Because ego has no place when health is at stake. Consider the fact that prolonged burnout can even heighten susceptibility to depression and illness.

Unfortunately, Mech can certainly seem like the perfect breeding ground for stress-induced burnout and complications. I take issue with the student culture that accepts these as necessary corequisites to being a Mech student, and worse yet, the subculture that flaunts their stress to signal the program’s superiority over others. Stress is how our bodies tell us that something about our situation needs to change. A healthy amount of stress can motivate us to excel, while stress in excess immobilizes. There is nothing commendable or useful about the latter.

My fear while addressing my burnout was “what if by letting myself relax, my grades slump and the drivetrain team loses momentum?” It felt like an impermissible compromise. But the reality was that my grades and drivetrain team were suffering as a result of my burnout anyway. It was useful to reframe self-care as an investment in my future performance, especially for when it might really matter, like during midterms, finals, or the homestretch just before a submarine competition.

Mech demands more than academic prowess—it demands resilience, reflection, and adaptability. You might be pleasantly surprised what the occasional movie, workout, or hangout might do for your mental health and grades. I certainly was.