Welcome back reader,

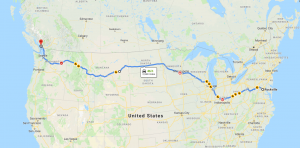

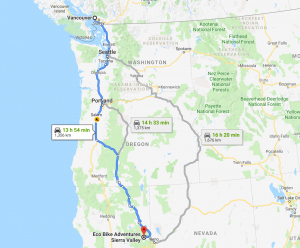

I the last post I discussed the preparation leading up to our first competition and the journey we took to get there. In this one, I’d like to recount the details of the festival itself, including the weather, the camping, the food, the people and most importantly, the race.

Firstly, I wanted to talk a bit more about my team’s purpose and electric bike as a whole. ThunderBikes was founded by my friend and classmate, Bhargav, last year with the goal of promoting the use of e-bike as a mode of transportation. The team is doing this through high performance bike projects as well as encouraging and helping their own members to do their own electric conversion. Less than 5 percent of Vancouver residents commute to work by bike. This is often largely due to the extended range of most commutes, as housing in the city or on campus is very expensive. Electric bikes is a fantastic method of transportation and significantly increase the range of an average commute. This push towards e-bikes will also help lower the congestion of commuting by car or public transit to campus, improve student health through exercise, and create eco-friendly transportation methods around vancouver.

Camping

Camping outdoors means exposing yourself to the elements, both hot and cold. And California in July is both hot and sunny in the day and quite chilly during the night. Fortunately for us, it did not rain. If you plan on camping this season, remember to check the weather forecast (highest and lowest temperature) and bring sufficient layers to dress up or down depending on the time of day. There was a lot of bugs at night, as they seek sources of light, so bring along bug spray. At night, the temperature dipped below 10°C, so invest in a warm sleeping bag and a comfy pad before heading out.

One Friday, we delegated one member to go grocery shopping while the other two stayed at camp to set-up. We had bought a butane stove, a saucepan and some camping dining ware at a nearby walmart. For dinner we boiled pasta and had it with canned chilli. We brought along soda and water in a cooler, which was great to keep everything cold. On Saturday breakfast, we boiled water to cook oatmeal, to which we added strawberries and peanut butter. For lunch, we grilled some corn on the cob right on top of our stove. Dinner was a western bbq provided by EcoBikes which included dishes including baked beans and beef brisket.

Race Day

We woke up early Saturday morning to prepare for our race. We signed up for only one race out of many (we qualified for the throttle assist class, but there were also pedal class, adaptive class, and super class). Bhargav, our rider for the race, went on a test run of the trail. Courtesy of EcoBike, I was able to borrow a pedal-assist bike and followed after him. The trail was a 10 km loop up into the mountains, consisting of big inclines and declines, countless turns, jumps and different rough surfaces (rocks, mounds, streams). It took me half an hour to complete the course, and I finished with sore hands and a very dirty bike. After our test ride, we did an overall inspection of the bike, and performed last minute adjustments to the suspensions, the pressure tires and secured all loose wires. We then left the bike to charge.

The race started at 2:30 P.M. One by one the racers stepped up to the start line and rode off; they were timed individually. As Bhargav rode off towards the mountain, we cheered him on and then waited anxiously for him to come back. 20 minutes later, we saw him slowly approaching the finish line. After he crossed, we slowly made our way towards the barn, and I noticed the flat tire. It turned out that our bike got a flat tire on the rear about 1 km into the trail, but the rider did not notice. He then crashed on a steep decline and was unable to keep going. Unfortunately, we could not finish the trail, and the bike suffered some damage to the rear wheel. We were disappointed with the result, but admitted it was down to track experience and unlucky failure, rather than a design flaw.

Other teams

Besides competing, this festival was a great chance to network with other teams. Some prominent e-bike designers attended, including Stealth and HPC. HPC sponsored some of the events and brought their own riders to compete using their bikes. Stealth had some of their models for us to test ride, and merch to give out. We also met some individuals who were just e-bike enthusiasts there to enjoy the atmosphere. Among them was Cutis, our camp neighbor who we shared some beers with; he’s a seasoned mountain biker who recently transitioned into e-mountain biking as he got older, and Daniel, a professor at Sonoma State University who built his own battery. Everyone there were very friendly and open to talk about their e-bike knowledge and experiences. We definitely took some inspiration from them that we could use for our future builds.

Conclusion

The Lost Sierra E-bike Festival was a great experience and a fun trip. Although the result was not what we wanted, we took a lot of positives from our design; we also learned a lot about other designs and have ideas for next year’s build. I would highly recommend going to competition with your design team if you have the chance, as you would definitely not regret it in hindsight.