I read a terrific paper this week by Jennifer McCrickerd (Drake University) called, “Understanding and Reducing Faculty Reluctance to Improve Teaching.” In it, the author lists 6 reasons why some post-secondary (#highered) instructors are not interested in improving the way they teach:

- instructors’ self-identification as members of a discipline (sociologists, biologists, etc.) instead of as members of the teaching profession;

- emphasis early in instructors’ careers (graduate school, when working to attain jobs and then tenure) on research and publishing;

- instructors’ resistance to being told what to do;

- instructors’ unwillingness to sacrifice content delivery for better teaching;

- instructors’ momentum and no perception that current practices need to change;

- risk to sense of self involve with change by change by instructors

These are succinct descriptions of the anecdotes and grumblings I hear all the time, from instructors who have transformed to student-centered instruction, from instructors who see no need to switch away from traditional lectures and from my colleagues and peers in the teaching and learning community whose enable and support change.

What makes McCrickerd’s paper so good, in my opinion, is she connects the motivation behind these 6 reasons to research in psychology. In particular, to Dweck’s work [1] on fixed- and mutable-mindsets (with fixed-mindset, you can either teach or you can’t, just like some people can do math and some can’t) and to Fischer’s work [2] on dynamic skill theory (which posits, “skill acquisition always includes drops in proficiency before progress in proficiency returns”).

I won’t go into all the details because McCrickerd’s paper is very nice — you should read it yourself. But there’s one facet that I want to examine because of how it relates to a blog post I recently read, “How I cured my imposter syndrome,” by Jacquelyn Gill (@jacquelyngill on Twitter). She writes,

I felt like I’d somehow fooled everyone into thinking I was qualified to get into graduate school, and couldn’t shake the anxiety that someone would ultimately figure out the error. When something good would happen– a grant, or an award– I subconsciously chalked it up to luck, rather than merit.

With that resonating resonating in my head (yes, resonating: I often feel imposter syndrome), I read that McCrickerd traces some instructors’ reluctance to “self-enhancement” which she describes as follows:

With that resonating resonating in my head (yes, resonating: I often feel imposter syndrome), I read that McCrickerd traces some instructors’ reluctance to “self-enhancement” which she describes as follows:

Most Westerners tend, when assessing our own abilities, character or behavior, to judge ourselves to be above average in ability. In particular, we view ourselves as crucial to the success of our accomplishments but when not successful, we attribute the lack of success to things other than our actual abilities.

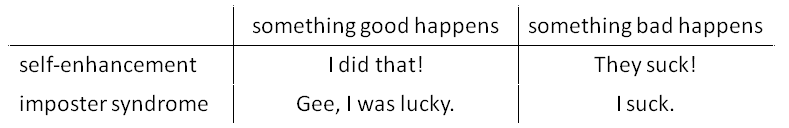

The streams crossed and I scratched out a little table in the margins of the paper:

McCrickerd points out it is only through dissatisfaction that we change our behavior. An instructor with an overly-enhanced self sees no reason to change when something bad happens in class. “Not my fault they didn’t learn…”

And who else does a lot of teaching? Teaching assistants, that’s who. Graduate students with a raging case of imposter syndrome. When something goes wrong in their classes, “It’s my fault. I shouldn’t even be here in the first place…”

Yeah, that’s a real motivator.

So, what do we do about it.Again, McCrickerd has some excellent ideas:

[I]nstructors need to be understood to be learners with good psychological reasons for their choices and if different choices are going to be encouraged, these reasons must be addressed.

The delicate job of those tasked with helping to improve teaching and learning is to engage these reluctant instructors so they begin to look at learning objectively, then to demonstrate there are more effective ways to teach, to closely support their first attempts (which are likely to result in decrease in proficiency) and to continue to support incremental steps forward. It’s not always easy to start the process but if there’s one thing I’ve learned in my job, it’s the importance of making a connection and then earning the trust of the instructor.

Now, go read the McCrickerd paper. It’s really good.

References

[1] Dweck, C. 2000. Self-theories: Their roles in motivation, personality and development. New York, NY: Taylor and Francis Group.

This Scientific American article by Dweck is a nice introduction to fixed and mutable minds-sets

[2] Fischer, K., Z. Yan, & J. Stewart. 2003. Adult cognitive development: Dynamics in the developmental web. In Handbook of developmental psychology, ed. J. Valsiner & K. Connelly, 491-516. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. [pdf from gse.harvard.edu]

Image “The Show Off. Part 2” by Sister72 on flicker (CC)

My wife works with people with developmental delays, like autism and fetal alcohol spectrum disorder. Her niche is sexual health. Imagine the hormones of a teenaged boy with the impulse-control of a 5-year-old. She often gets called in when some Grade 6’er starts whippin’ it out – either for the reaction he gets or because he doesn’t realize that’s not what typical Grade 6ers do.

My wife works with people with developmental delays, like autism and fetal alcohol spectrum disorder. Her niche is sexual health. Imagine the hormones of a teenaged boy with the impulse-control of a 5-year-old. She often gets called in when some Grade 6’er starts whippin’ it out – either for the reaction he gets or because he doesn’t realize that’s not what typical Grade 6ers do. I’m struggling with an issue. I can’t decide, or maybe I’m afraid to admit, if I’m being naive. Or perhaps so inexperienced, I’m blinded by imposter syndrome, the feeling that you really don’t belong in the group of experts you find yourself in. I’m hoping that by the time I get to the end of this post, I’ll at least have a better understanding of my confusion.

I’m struggling with an issue. I can’t decide, or maybe I’m afraid to admit, if I’m being naive. Or perhaps so inexperienced, I’m blinded by imposter syndrome, the feeling that you really don’t belong in the group of experts you find yourself in. I’m hoping that by the time I get to the end of this post, I’ll at least have a better understanding of my confusion.