Algunas apostillas sobre la visita de Rita Segato

Algunas apostillas sobre la visita de Rita Segato

(y en defensa del Koerner’s Virtual)

«Tout le malheur des hommes vient d’une seule chose, qui est de ne savoir pas demeurer en repos, dans une chambre» Blaise Pascal

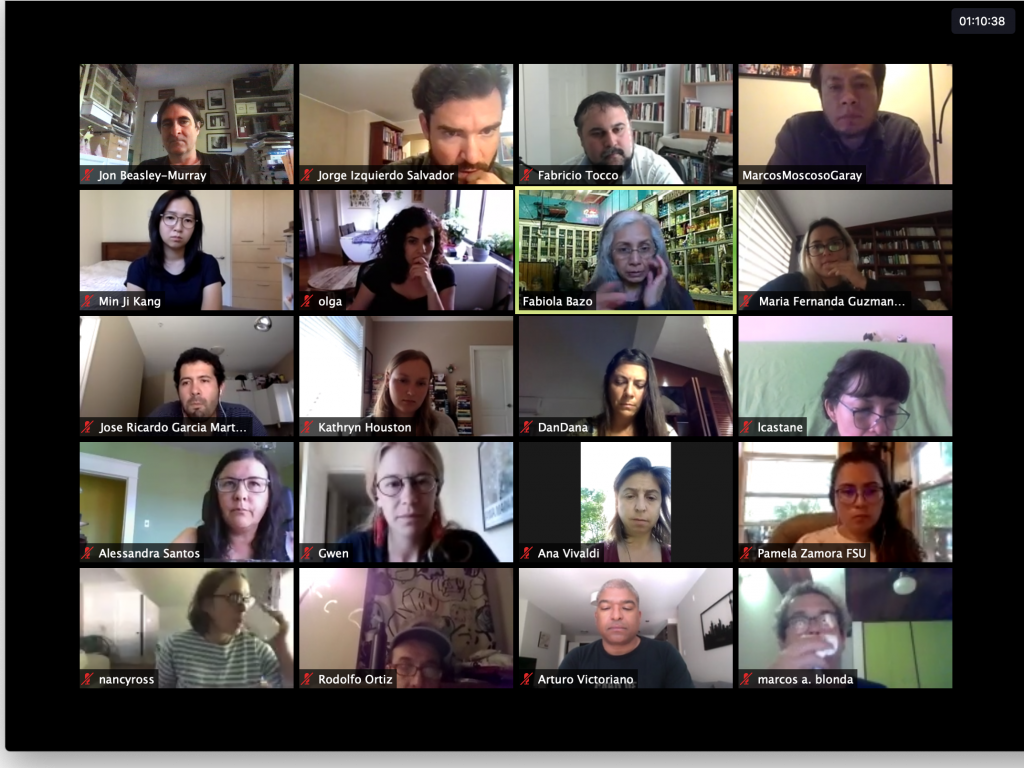

Con temor a caer en esa labor de aquellos que reescriben —porque muchas veces traicionan— lo que se dice en las conversaciones, habría que recuperar algunas preguntas y puntos que se tocaron muy brevemente en la charla que hace algunas horas tuvo el grupo del “Virtual Koerners” con Rita Laura Segato, que muy amablemente nos regaló más del tiempo que había acordado estar con nosotros.

Hay, al menos dos preguntas que requieren atención y discusión (quizá faltan otras):

- ¿Cómo cambia el mandato masculino en el tiempo? ¿Es correcto el decir que en estos tiempos apocalípticos del capitalismo este mandato demanda más violencia del varón? ¿Ha cambiado el rol de las mujeres en este mandato?

- ¿Cómo la domesticidad, que “nada tiene de privado o de íntimo”, se puede seguir reconceptualizando en tiempos de pandemia, cuando es impuesta por el Estado y sigue complicando la relación entre el mundo “de afuera” y el mundo “casa adentro”?

Las preguntas, de cierta manera, ratifican algo que se ha notado y anotado a la labor de Segato. Esto es que, detrás de la domesticidad y del rol emancipador de la mujer, al menos en esa necesidad de regresar o restituir esa historia de la prehistoria del patriarcado, esa historia dual y no binaria —que parece el primer objetivo de la labor feminista [según Segato, otra vez]—, hay un esencialismo. Por otra parte, estas preguntas pudieran encontrar cierta resonancia y respuesta en esa idea de Segato en abandonar la idea de humanidad. Es decir, que aunque el rol de las mujeres pudiera haber cambiado, o si el estado es el que exige la domesticidad, la salida que habría que buscar es la renuncia a la humanidad, construida e interpelada por el estado, y apostar por una existencia. Segato en la charla hablaba de un paisaje no-converso. Hay, quizá, un umwelt sin estar en la misma baldosa, un lugar que es condición de nuestras condiciones, por retomar eso que escuchamos en la charla de Alberto Moreiras. No obstante, la pregunta, otra vez, al menos para mí, sería pensar si todo esto no es una nueva demanda por la acción y por lo tanto no una demanda por la fascinación de la imposibilidad, de la muerte y de la crueldad, sino una afirmación más de la vida, que a todos nos excede. El comentario sobre estas preguntas es más una invitación (y a la vez una demanda) a la charla.

La reunión con Segato comprobó que hay muchos de sus temas que no nos mueven el piso ya. Esto es que con leer la obra de un autor basta, hasta cierto punto. Las charlas en vivo son más carácter institucional. Sin embargo, hay algo no codificable en ese cuadro de zoom, y en esos parches que se extienden en la pantalla del ordenador o del celular. Justamente, esa empresa, la de acercarnos a eso que escapa al carácter institucional, es lo que da más ganas para seguir leyendo o escribiendo, y más aún las charlas como la de hoy ratifican que tener desacuerdos es más productivo que juntar un puñado de acuerdos entre gente apática y que no quiere participar de ninguna forma (ni siquiera tomando notas). Habría que mantener abierto el canal con Segato y con los demás invitados (y sobre todo participantes del Koerner’s Virtual—sean ocasionales o frecuentes). Tal vez esos canales, a la larga de esta pandemia, que sigue sacudiendo viejos hábitos, puedan darnos otras respuestas.

In her chapter, “Patriarchy: From the Margins to the Center” (from La guerra contra las mujeres [2017]), Rita Segato goes further. We are all trained to be psychopaths now, she tells us, as part of a “pedagogy of cruelty” that is the “nursery for psychopathic personalities that are valorized by the spirit of the age and functional for this apocalyptic phase of capitalism” (102). Segato presents a brief reading of Stanley Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange to make her point, though what she sees as “most extraordinary” about the film is that the shock with which it was received when it came out (in 1971) now seems to have almost totally dissipated. What was once taken as itself an almost psychopathic assault on the viewer’s senses is now just another movie; this shift in our sensibility is “a clear indication [. . .] of the naturalization of the psychopathic personality and of violence” (102). The narcissistic “ultra-violence” of the gang of dandies that the film portrays is now fully incorporated within the social order that it once seemed to threaten.

In her chapter, “Patriarchy: From the Margins to the Center” (from La guerra contra las mujeres [2017]), Rita Segato goes further. We are all trained to be psychopaths now, she tells us, as part of a “pedagogy of cruelty” that is the “nursery for psychopathic personalities that are valorized by the spirit of the age and functional for this apocalyptic phase of capitalism” (102). Segato presents a brief reading of Stanley Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange to make her point, though what she sees as “most extraordinary” about the film is that the shock with which it was received when it came out (in 1971) now seems to have almost totally dissipated. What was once taken as itself an almost psychopathic assault on the viewer’s senses is now just another movie; this shift in our sensibility is “a clear indication [. . .] of the naturalization of the psychopathic personality and of violence” (102). The narcissistic “ultra-violence” of the gang of dandies that the film portrays is now fully incorporated within the social order that it once seemed to threaten. We are delighted to start today with a discussion with

We are delighted to start today with a discussion with

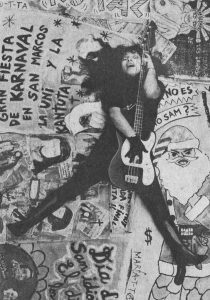

María T-ta had a very assertive discourse about female sexuality, and made it clear that she did “with her life and with her body what she wanted.” Her lyrics, presentations, interviews and publications evidenced her critique of machismo in Peruvian society. For instance, one of her songs describes the rape of a maid (a racialized woman from the Andes) by the son of a white family in a rich neighbourhood in Lima.

María T-ta had a very assertive discourse about female sexuality, and made it clear that she did “with her life and with her body what she wanted.” Her lyrics, presentations, interviews and publications evidenced her critique of machismo in Peruvian society. For instance, one of her songs describes the rape of a maid (a racialized woman from the Andes) by the son of a white family in a rich neighbourhood in Lima.