Background and Instructions:

This “Virtual” Tour was created in Spring, 2020, when the Covid19 emergency prompted a move to remote, online instruction. A formerly Teaching Assistant-led field trip in GEOS 102* needed swift conversion to virtual operation, and here is the result.

* An introductory Physical Geography course at UBC Vancouver called Our Changing Environment: Climates and Ecosystems

NB: If you want a a guided tour through the actual forest, check out our mobile-app led Augmented Reality version in Echoes (this replaces the original Motive.io-Explore AR version)

The tour takes one through a large remnant of Coastal Douglas Fir forest in Pacific Spirit Park, Point Grey, Vancouver, BC to examine the species composition, structure and dynamics, particularly in relation to human and natural disturbance processes. It begins at the trailhead of Spanish Trail, starting at the end of College Highroad:

Map of tour route and stops (blue markers) along Spanish Trail, Pacific Spirit Forest. Zoom in or out, click the blue markers to see a description of each stop, and learn more in the field trip, below.

Students enrolled in GEOS 102: First, read the lab handout in the LMS (Canvas), the textbook sections referred to in the handout (Arbogast et al 2018 or equivalent, e.g., Strahler & Archibold 2011; Christopherson et al., any ed.) and the background information about this site, to familiarize yourself with concepts of disturbance and succession (more information about these processes will follow in lecture and this trip). Have your dichotomous species id key handy.

Anyone else who wishes to take the trip: I include Background information on this site here, along with the GEOS 102 question set, in case you wish to test your knowledge! Click here for a species id key (adapted from Straley and Harrison 1987; Diagram designed by UBC MSc. student, Nick Rong, and updated by K Hurley and N Hewitt).

To view the 360 Photos (photospheres) below, first click on the photo – it will open in Google Photos; then click anywhere on the photo to launch the 360 viewer; finally, scroll around the image (left – right, up – down) to explore the scene in 360 degrees.

We hope you enjoy learning about the forest and the trees!

Land acknowledgement: We respectfully acknowledge that this tour takes place on the traditional, ancestral and unceded territory of the xʷməθkʷəy̓əm (Musqueam) people, in a place that they call ʔəlqsən.We are grateful for the chance to study and enjoy this ecosystem, which they have sustained for millennia, and continue to do so.

Begin the Tour:

1) Play this video recorded at the head of Spanish Trail introducing the tour (Note: The City began gardening with leaf blowers, so this video is a little noisy!)

2) Click image below to open the 360 photo at the Spanish Trail Trailhead [Remember to then click anywhere in the image to launch the 360 viewer; scroll up, down, left, right to view photosphere].

Using the photo, be a field ecologist and use your observational skills, paying particular attention to visible evidence of:

a) species composition: inferred from, e.g., bark characteristics (color, texture/pattern); plant type, based on life-form by forest layer (shrub vs tree), stem morphology and branch pattern, etc.

b) age structure: inferred from the range of stem sizes visible. Is this a stand with even-aged stems or one with stems in lots of different size/age categories?

This, along with the other photospheres, was taken the day the video was filmed, on Mar 20, 2020, before trees have begun to leaf out. Thus, the deciduous trees are leafless.

As stated in the video, the disturbance event was a human-caused one. Clearly, the development plan did not go through, explaining why you see second-growth forest here, rather than apartments!

Hardwood Forest Stop (Stop 1)

1) Play Instructional Video 2: In the hardwood forest

[v2, edited for PG Lab Manual, 2nd ed, Jul 2021].

2) Click image below to open 360 photo of Stop 1 [Click image, click centre to launch 360 viewer, scroll].

The same scene in midsummer, June 17 2020, with deciduous trees fully leafed out.

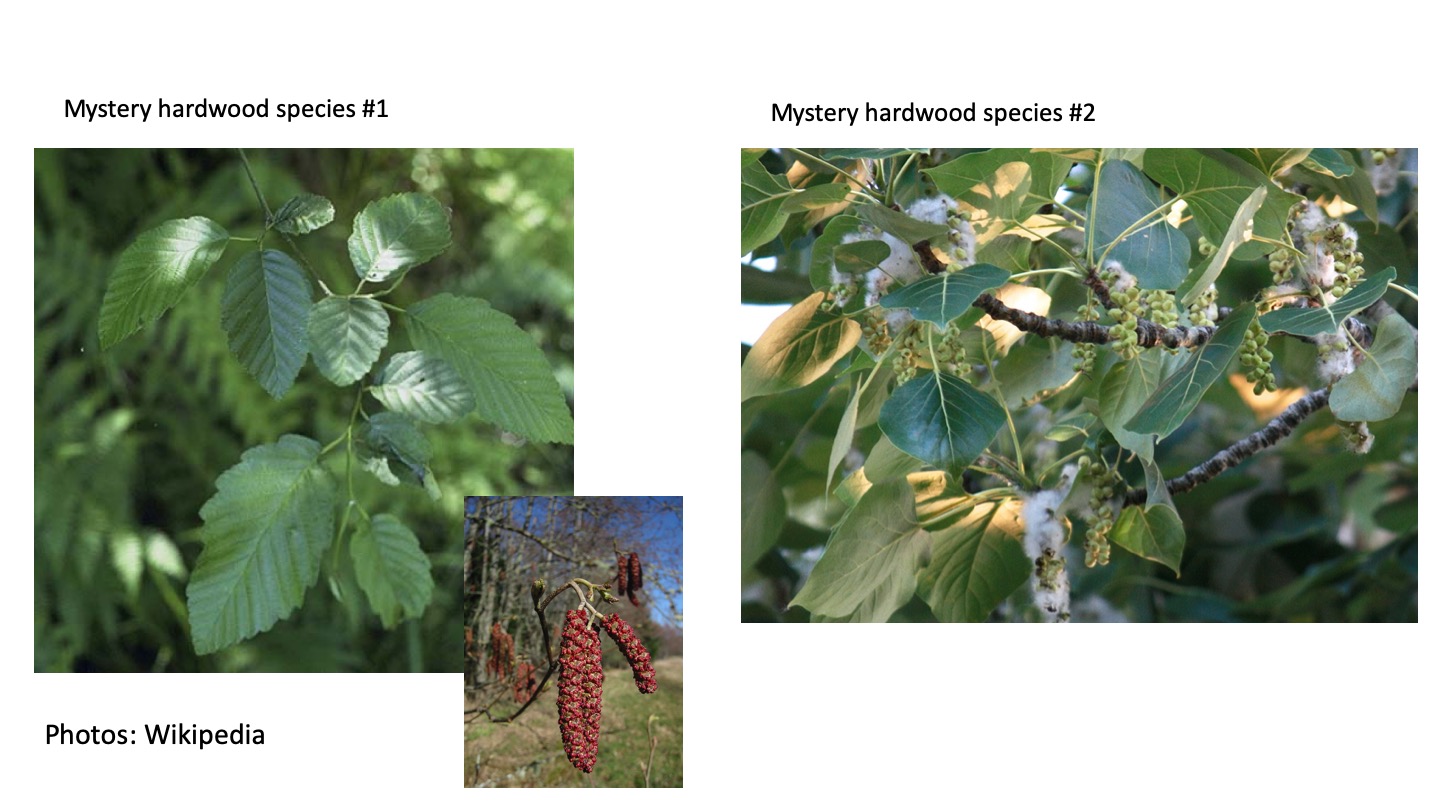

Can you identify the species in the video and in Figure 1? Use your key to find their latin binomials and common names. Both species are early successional, and these individuals recruited shortly after site had been disturbed when there was no tree canopy, little competition, and ample light.

What sorts of characteristics do you think these species have that allow them to arrive and thrive in recently disturbed sites (use your text as a reference)? These are adaptations – traits evolved over time, and they help to match the species with the type of environment (e.g., open, recently disturbed sites; shady, undisturbed sites) for which it is specialized.

- Things to consider: 1) “seed size/seed numbers” — there is a tradeoff between the size of a species’ seeds and the number of seed it can produce on limited resources – species tend to produce either many small or a few large seeds; 2) Seed dispersal characteristics: do the seeds have appendages such as plumes or wings, etc., to be scattered broadly by wind, or tasty coverings to attract animal dispersers and be placed in specific locations? More importantly, how do these dispersal syndromes affect the chances of arriving and surviving in particular sites? Hint: species with many, small seeds have a decent chance of at least some arriving in recent openings; species that produce a few large seeds have larger seed nutrient reserves to enable establishment in closed, shady sites where sunlight at the ground may be limited; at the same time, in these coastal forests, most tree species fall into the many-small seeds grouping. Nature often defies our simple attempts at categorization!

Are there other sorts of disturbances that might affect the forest? You might see some clues of more small-scale disturbance in the 360 photo. (Hint: any broken branches? Signs of disease?) A discussion of disturbances, small and large-scale, is found in your text chapter (Strahler and Archibold, Chap 21).

How do you think this site will change in future? In the following video, UBC Geography PhD candidate and former GEOB 102 TA (2018-19), Kevin Pierce, chats about clues that indicate how this early successional hardwood stand may change (videographer K Hurley, Mar 2019; shared with permission from KP).

Now play the video below, in which a biogeographer (guess who?) demonstrates how to date disturbance. She extracts a ring series (tree-ring core) from one of the largest, and oldest, stems at Stop 1. The ring counts and age of this tree will tell long ago it established, indicating the approximate timing of the disturbance event that led to stand initiation at the site (This is species x – the one you identified first).

With this information and your dichotomous key, you should be ready to answer the first few questions in the lab. Next, proceed to the boardwalk site….

Boardwalk Site

1) Play Video 3: Boardwalk Station [v2, edited for PG Lab Manual, 2nd ed, Jul 2021].

2) Click image below to open 360 photo of Boardwalk

Based on the information you learned, what sort of disturbance occurred here? How/Why? Hint: What do you know about Canada’s National animal?

Entering the Needleleaf Forest

1) Play Video 4: Entering the needleleaf forest

In the video above, I pointed out a species of shrub that is native to this forest, salal. Find out more about this and other native understory species, including red huckleberry, sword fern and dull Oregon grape in UBC Forestry’s Coastal Plants of BC’s videos (Culbert 2018), filmed here in Pacific Spirit Park!

I also pointed out a species non-native to the area, pictured in the following photos:

As you may infer from the photo in Fig. 3, this European invader has been very successful at colonizing the hardwood forest, with several individuals visible in the photo. What do you think makes it so successful? Why is this species so abundant in the hardwood forest? Other introduced invasive species present here include Laurel (Prunus amygdala). Note that holly and laurel are both evergreen woody species adapted to environments with mild rainy winters. They thus benefit from Vancouver’s West Coast Marine climate, being able to photosynthesize throughout winter, in contrast to native deciduous hardwoods.

What impact do invasive species have on native species in the forest? Listen to this audio clip for more information: Invasive Species in Pacific Spirit Park

What actions do you think could be taken to manage invasive species and the threat they pose to biodiversity?

Needleleaf Forest Stop (Stop 2)

1) Play Video 5: Needleleaf forest [v2, edited for PG Lab Manual, 2nd ed, Jul 2021].

2) Click image below to open 360 photo of the Needleleaf forest, Stop 2

The same scene in midsummer, June 17 2020. Or try scrolling around this 360 video of the same scene (video resolution is poor, but scene is interesting and has sounds of birds present!).

You have entered a remnant of Coastal Douglas fir forest, one of BC’s Biogeoclimatic Ecosystem Classification System (BEC) zones, described in detail here. You’ll notice that the canopy trees are larger and older than those in the hardwood forest, indicating the longer time since major disturbance (and later successional stage) at this site.

Identify the three conifer (needle-leaf) species discussed in the video based on their leaves and bark, using your species id key. In Figure 4 (top), you can see pictures of cones from the first and third needle-leaf species examined in the video (we saw cones of the second type in the video), and (bottom), the species with silver needle undersides heterogeneous needle lengths. This species has an apical meristem (the stem tip or branch leader at the top of the tree) that tilts over like a Dr. Seuss Christmas tree (perhaps not visible in the photo, but something to look for when next you visit a BC coastal forest).

Other native species present in this forest include the understory species of Acer (maple) mentioned in the video with “vine” in its common name (hint) and a canopy species of maple with very large leaves (hint). The latter, large-leaved maple, is actually a co-dominant species in this forest. It is shade-tolerant and reaches the canopy alongside the 3 conifers in late-successional stands. Find both in your Dichotomous key; for precise botanical information on the viney species, watch this Coastal Coastal Indicator Plants of BC video. Now, you may wish to try this tree species id knowledge test.

Notice, in the 360 photo, the large pile of earth with young hemlock trees (saplings) growing on it along the east side of the trail (opposite from the dog). This is a tree-fall or tip-up mound, an important micro-habitat and “safe site” for many forest species (Huckleberry and Western hemlock, for instance). The term safe site (coined by eminent British ecologist John L. Harper), refers to an establishment site protected from hazards (e.g., burial from leaf-litter) and providing suitable conditions (fresh, exposed soil) for species’ seed to germinate and establish. How does a tree-fall mound qualify? These sorts of micro-habitats become more available in complex environments such as this, where forest trees have had time to live out their life cycles, decay, and created decomposed stump or branch litter, etc.

More about BC’s Coastal Forests, Past and Present:

BC’s southern coastal rainforests are considered to be some of the most productive ecosystems in the world. Their dominant evergreen needle-leaf species retain foliage throughout winter and thus benefit from the large amounts of precipitation that fall during Vancouver’s mild winters. In this environment, deciduous trees (broad-leaf species) are compromised by the fact that they are adapted to lose leaves during cold periods, and can photosynthesize only in summer when moisture becomes limiting. To see the seasonal patterns rainfall and temperature that characterize BC’s West Coast Marine Climate, see your course notes for a climograph, or this link.

Consider the kinds of site conditions present here: cool and shady or hot and sunny (which?). How do they affect the sorts of species growing here (and visa versa?). As you consider the roles of species in this forest, you may wish to listen to this audio-clip from our AR version of this trip.

As with the first site you examined (Stop 1), this area experienced large-scale human disturbance (in this case, by extensive logging/tree-cutting), but less recently. See a photo of what this looked like at this link (clearing of Point Grey, 1914, UBC Archives). One can assume that the forest is approaching a size (age) structure and species composition of old-growth forest, and perhaps more closely resembles the historical forest, that would have been common throughout the regions prior to European settlement. That said, it probably lacks the complexity and very large, old (>500 years age) stems that would have occurred here otherwise (see below). How long ago was this site disturbed by logging (how old was the tree I cored)? Successional changes have thus proceeded for longer than at Stop 1, and this greater time since disturbance helps to explain the difference in species composition and structure between the two sites.

There are other sorts of disturbance here including some more regular, small-scale disturbance. When we take students through this site, we pass some burned out stumps (hint, for question on the lab about other disturbances at this site).

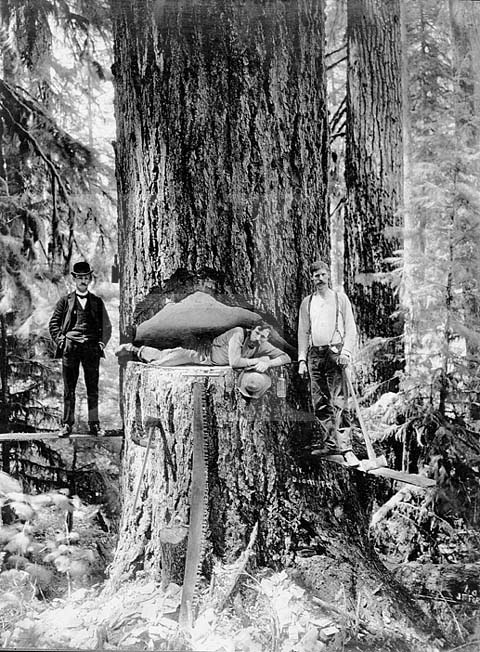

Think about the forest before the logging event. It would have supported stems much. more massive than those present (Fig. 6).

Stumps associated with these wide-scale logging events are found throughout Pacific Spirit forest (Fig. 7). How do you think these extractive forestry practices affected the ecosystem? Would there have been long-term impacts on structure and function? (For some answers and related discussion see here) Of course, disturbance and change is a feature of natural systems, but perhaps the scale of destruction from logging operations was atypical. In this sense, this little piece of Douglas fir forest represents an altered remnant, and is perhaps illustrative of the “Anthropocene”.

Consider how post-settlement forest practices compare to those of the original people of Point Grey, the xʷməθkʷəy̓əm (Musqueum). One Indigenous practice of forest harvesting, cedar bark stripping, was touched on in the video (and see: Snively and Corsiglia, Chap 7). This was non-destructive: Trees survived, gradually sealing off wood where bark was stripped via cambial tissue growth (growth from cambial cells located just beneath the bark that produce the tree’s annual rings). Affected trees retain residual scars that identify them years later, and are referred to as “culturally modified trees” (CMT). And recent research indicates that Indigenous peoples cultivated gardens that had lasting impacts on the forest structure and diversity in the Pacific Northwest (Armstrong et al. 2021). For example, archaeological village sites were accompanied by groves of perennial fruit (eg, Pacific crabapple (Malus fusca) and nut (Hazelnut (Corylus cornuta) bearing woody species, in otherwise closed needle-leaf stands; and these legacies persisted for up to 150 years, with implications for native wildlife including pollinators.

There is so much more to learn about the Coast Salish (Musqueum, Squamish and Tsleil-Waututh Nations) and other Indigenous peoples, whose legacy is embedded in the history of southern BC’s forest ecosystems. UBC’s Departments of Geography, First Nations and Indigenous Studies, and the First Nations House of Learning are all places to start, if you are keen!

You may wish to end with this audio-clip that considers a future affected by climate change in BC Forests (from the app-led AR version of this trip).

~ Trip End ~

New:

This trip is part of an open education lab manual (1st edition released August 2020). The updated 2nd edition (2021) is available at:

To view the 360 photos and videos in a seamless tour, try the VR tour created in H5P found at this page.

Good luck and enjoy the virtual ecosystem experience!

References and Further Reading:

Armstrong, C., J. Miller, A. C. McAlvay, P. M. Ritchie, and D. Lepofsky. 2021. Historical Indigenous Land-Use Explains Plant Functional Trait Diversity. Ecology and Society 26(2):6. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-12322-260206

Culbert, P. 2018. Coastal Plants of BC – UBC Forestry videos used with permission. UBC Faculty of Forestry, at: http://bit.ly/BCPlants

Hewitt, N., Chapter 10: Plant Geography (new segments for the 1st Canadian edition) in Arbogast et al. 2018. “Discovering Physical Geography”, 1st Canadian Edition, John Wiley & Sons, Toronto.

Strahler, A.H. and Archibold, O.H. 2011. “Physical Geography”, 5th Canadian Edition, John Wiley & Sons, Toronto.

– Chapter 21, especially sections dealing with “disturbance” (p. 526-9) and “succession” and pioneer species (p. 530-3)

Straley, G.B. and R.P. Harrison. 1987. An Illustrated Flora of the University Endowment Lands. Botanical Garden, Technical Bulletin #12. University of British Columbia, Vancouver B.C.

UBC Geography. 2019. Lab 4 Handout: Soils, Tree Species Composition and Disturbance History in Pacific Spirit Park. In GEOB 102, Our Changing Environment: Climate and Ecosystems, Dept. of Geog., UBC

Acknowledgements

I thank Stepan Wood for filming the instructional videos and assisting with photography; Kevin Pierce for sharing his TA experience in a video; Kelly Hurley for assistance with the tree ring coring video; the many course TA’s who, in the past, guided students through this trip in person, and shared their insights. The route and framework for this tour is based on a TA-led field lab designed years ago for GEOS 102 by Dr. Greg Henry, UBC Geography.

Creative Commons Licence

Pacific Spirit Forest Virtual Field Trip by N Hewitt (2020) is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Based on a work at https://blogs.ubc.ca/alpineplants/pacific-spirit-forest-tour/

If you make use of this resource, please let me know, and in which course you have applied these ideas. Thanks! Nina Hewitt, GEOB 102 Instructor, 2019-20, nina.hewitt@ubc.ca