Our final text of the year in Arts One is Moore and Gibbons’ graphic novel Watchmen. We only had one seminar meeting on this text this week, as opposed to our usual two. Which means I didn’t spend as much time going over the text, deciding on my own interpretations, as usual: usually I spend at least 3 hours before each seminar, and this week I spent just 3 hours before one seminar rather than two. I wanted to spend some time in this blog post going through my thoughts on a few things–writing them out is really the only way they get clear for me.

This first post is starts off talking about Rorschach, then moves into broader themes related to black/white, dark/light and. I also wanted to write about my concerns regarding the novels portrayal of women (which really bothered me), but I’ll save that for the next post (hopefully tomorrow) b/c there is a lot to discuss here already.

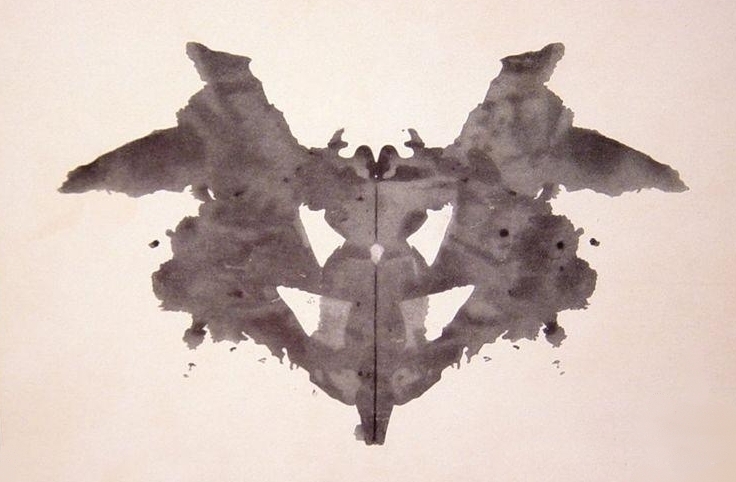

Rorschach Blot 1 from Wikimedia Commons. Public domain.

Why do I dislike Rorschach?

A number of people disagreed on whether they liked this character. Some of us (myself included) find him to be highly questionable as a person, and others sympathized with him because of his bad childhood, or thought he was at least somewhat likeable in other ways. Why don’t I like Rorschach? I’m trying to figure that out.

One obvious thing, for me, is that he reads and trusts the New Frontiersman. This paper publishes racist things, like saying the Ku Klux Klan may have had “later excesses” but “originally came into being because decent people had perfectly reasonable fears for the safety of their persons and belonging when forced into proximity with people from a culture far less morally advanced.” And then again: the Klan worked “to preserve American culture in areas where there were very real dangers of that culture being overrun and mongrelized” (end of Chpt. 8). Now I just don’t see any way to read these statements that isn’t racist. And I don’t believe that as readers the point is for us to take this paper seriously or sympathize with it. Since Rorschach does read this paper, and thinks they’re the only ones he can trust, that tarnishes him for me.

I suppose one might say that well, if anyone is going to print his story it’s going to be a paper that doesn’t mind printing things that sound crazy or controversial in the name of what it thinks of as truth. But he does read the paper himself, going to the news agent Bernard to get it most days.

He also says a couple of things in the first issue that are offensive. After visiting Heidt he asks: “Possibly homosexual? Must remember to investigate further” (1.19). As if being homosexual is something that he needs to investigate, as if there is something about it that requires his further attention rather than just being, well, a fact like someone being heterosexual. Next, as Laurie rightly notices, he refers to the Comedian’s attempted rape of Sally as one of the “moral lapses of men who died in their country’s service” (1.21). Laurie correctly gets upset about this seeming trivialization of her mother’s attempted rape.

These, I think, are the main reasons why I really can’t bring myself to like him. Yes, there’s also the violence he engages in, but arguably that’s against people who have done very bad things: the guy who kidnapped and murdered a child, the guys who came to his prison cell to murder him; wasn’t the man he killed to protest the Keene act a serial rapist? I can’t find that right now, but that’s interesting, in contrast to what he said about the Comedian. It’s not so much the violence that bugs me as the stuff above.

Black and white

At first I wondered whether the book was asking us to see Rorschach somewhat sympathetically b/c of his integrity, the strength of his convictions. There is something valuable in his idea that it’s wrong to let Veidt get away with what he has done, to not tell anyone. In issue 12, p. 23, he tells Jon that he can’t go along with keeping silent, because “Evil must be punished. People must be told.” Veidt can’t get away without being punished. There is some truth to this–he’s done something awful, and it is wrong to let him get away with it. But there’s also truth to the other side, that if they say something it’s likely to destroy a possible peace that millions of people have died to achieve.

As I said in class today, I feel like there’s a kind of dual extreme between Veidt and Rorschach: Veidt (and Dr. Manhattan agrees) says that the moral choice is clear–they must say nothing. Rorschach, too, thinks the moral choice is clear–evil must be punished. I think the moral choice isn’t clear here, that it’s not that black and white, to refer to Rorschach’s face and worldview. It’s a tough choice, and as Dan asks, how can humans make the decision? Perhaps, insofar as Veidt, Dr. Manhattan and Rorschach can make the decision, they are inhuman? But then again, Dan does make the decision to agree with keeping quiet, even though he at least struggles with it.

Rorschach’s face is made of fabric that is, in his words, “[b]lack and white moving, changing shape … but not mixing. No gray. Very, very beautiful” (6.10). Veidt refers back to this when he describes Rorschach as “a man of great integrity, but [who] seems to see the world in very black and white, Manichean terms,” and Veidt sees that as “an intellectual limitation” (last page of issue 11). This would speak against my statement above of Veidt seeming to be very sure of himself, somewhat black and white himself, but I think he is sure of himself as having decided that things are not either good or evil, but evil can be used in the service of good. And, as noted in class today, Rorschach refuses to “compromise”: “Not even in the face of Armageddon. Never compromise” (12.20; see also 10.22).

This black and white stance, this inability to compromise, reminds me of course of Miller’s The Crucible, where he criticizes (in his notes) the Manichean worldview of “us” vs “them,” where “we” are the good, the Godly, and anyone who is against us is diabolical. When then leads me to think also of the cold war, and both sides being unwilling to compromise, to back down for fear the other would take advantage of this. And I don’t think this is portrayed in the novel as a positive thing! When two groups or two people are both so certain they are right and refuse to move towards the other in any way, we are going to end up in conflict rather than, as we discussed in class today, coming together, uniting, connecting (which seems to be one of the things valued in the text).

Darkness and light

Lisbon Sunset in Black and White, Flickr photo shared by Pedro Ribeiro Simões, licensed CC BY 2.0

Finally, I want to think a little about the black and white images in the text. There is one panel that’s entirely black, and another that’s entirely white. The entirely black one is at the end of issue 6. Malcolm is looking at a Rorschach blot, thinking about why people argue, like he and his wife, when “Life’s so fragile, a successful virus clinging to a speck of mud, suspended in endless nothing” (6.28). He begins to muse about the meaninglessness of life, the “real horror” of life (echoes of Heart of Darkness?). Looking into the Rorschach blot, he tries to find meaning there, but can’t: “The horror is this: in the end, it is simply a picture of empty meaningless blackness. We are alone. There is nothing else” (6.28). And the next panel is merely blackness, as the ‘camera’ zooms in on the blackness of the Rorschach blot, followed by a quote from Nietzsche: “Battle not with monsters, lest ye become a monster, and if you gaze into the abyss, the abyss gazes also into you” (6.28).

I haven’t looked into this quote from Nietzsche much, but one possible interpretation of “the abyss” that fits with its use here is the utter lack of meaning, the emptiness of the universe in the sense that we just don’t matter; it will go on with or without us, uncaring. There is no meaning to life, no morality but what we impose on it. Rorschach says something similar in 6.26: “Existence is random. Has no pattern save what we imagine after staring at it for too long. No meaning save what we choose to impose.” And he imposes a stark, black-and-white morality on what is, at root, just empty blackness.

The all-white panel is at the end of issue 11 (11.28) when the creature Veidt has sent to New York arrives and kills millions of people. Bernie and Bernard are split apart into fragments the same way that Jon is before he becomes Dr. Manhattan. On 4.8, where he is depicted being pulled apart into fragments, he says, “the light is taking me to pieces.” The same thing is happening on 11.28, where the characters’ faces are lit up before they are taken to pieces and all that’s left is light in the last panel.

This light and the fragmentation that results is of course reminiscent of the atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and the “shadows” of people that were sometimes left on the walls are like the black images of Jon and then Bernie and Bernard left in the panels on 4.8 and 11.28. On 6.16, Malcolm points out the link between the silhouettes painted on the street walls and the atomic shadows. While the black darkness of meaninglessness is a horror, so is the blinding white light that tears us into pieces.

Veidt talks about ushering in “an age of illumination so dazzling that humanity will reject the darkness in its heart” (12.17) (again, echoes of Heart of Darkness). He is associated with ‘light’ in the sense of enlightenment, knowledge, but also with the light in the television screens he is continually watching. I’m not sure what to make of this, exactly, except it seems that the kind of light he brings, the “dazzling illumination,” is more like the cold, calculating rationality of someone who sees things only in the big picture, who weighs the lives lost to the lives saved as if they are mere numbers. It is like, I think, the inhuman perspective of Dr. Manhattan, whose view-from-all-time makes him think of human life as invaluable and unnecessary. He does, that is, until he sees individuals as improbable “miracles” (9.27)–until he begins to see the value of specific individuals, of their particularity coming from chaos as being miraculous. Veidt doesn’t care about individuals, only the abstract concepts of “humanity” and “peace” vs “war.”

Well, I think that’s quite enough musing for the moment. I’m not sure I’ve made anything any clearer for anyone else, but I do think I’m a bit clearer on some of my own views of these characters and this story.

I don’t think Rorshach is meant to be likeable or sympathetic. I like that he’s such a nutjob, and I’m fascinated by criminality in general, but he’s pretty much repulsive in every way. He may have a kind of righteousness and integrity, but he comes out of a cesspool and carries that with him.

His mask is an interesting metaphor. The black and white seems to represent a clear morality, but it’s also always changing shape. It suggests that there is a definite right and wrong, but it’s always relative to the situation – “no meaning save what we choose to impose.”

Rorshach’s mirror image, Veidt, is just as dislikeable and fascinating. He imposes an order on the world, acheiving peace through the murder of millions. But does he do it for mankind, or his own sense of self-satisfaction? He makes himself into a savior, but no one can know about it – like a god who no one worships but himself.

The black and white themselves both represent a kind of emptiness, different sides of the abyss, in the two panels. Veidt’s grand achievement is as empty as Rorshach’s efforts, and the struggle of life goes on.

So much for my mini-musing. It looks like you have a great course here. Too bad I wasn’t paying attention earlier.

I love your thoughts here, Paul! The point about the black and white panels representing two sides of the abyss, equally empty, is great. Black and white as opposites, but in a sense not really that different because they are two sides of the same thing–opposites are about the same thing, rather than being two very different, incommensurable things.

And your point about the black and white in Rorschach’s mask always changing is a good one too. I only got as far as thinking about what he says about them never mixing, not considering any further that they are in constant motion and what that might mean. Though I suppose the constant motion can also be related to them never mixing, always staying separate: they move, but they don’t cross each others’ boundaries.

Thanks for giving me some new ideas!