In Arts One this term we are reading Ian Hacking’s book, Rewriting the Soul: Multiple Personality and the Sciences of Memory (Princeton University Press, 1995). Here is a link to the Prezi used by our lecturer for this book, Jill Fellows.

In our seminar class on Wed. Jan. 21 I asked students to write down one or more of the “main points” they got from the text. I did this because there are many things that Hacking is talking about in this book, and I wanted to see if we could pull out a few that we thought were especially important.

In this post I am going to try to put these ideas from students together in some kind of coherent fashion (I hope), adding in my own thoughts on what I think are some of the main arguments in the book. I’ve grouped them into categories; others may group them differently, but this makes sense to me at the moment.

Note: this is a very long post! The first part is what we all said we thought were the main points in the text. If you want to jump down towards the bottom, I try to put this all together into a bigger picture, and then distill it down into an even bigger picture at the very end (literally, with pictures!).

What we said are the main points in the text

Making up people/the “looping effect”

The “looping effect” as explained by Hacking:

“People classified in a certain way tend to conform to or grow into the ways that they are described; but they also evolve in their own ways, so that the classifications and descriptions have to be constantly revised” (21).

“Being seen to be a certain kind of person, or to do a certain kind of act, may affect someone. A new or modified mode of classification may systematically affect the people who are so classified, or the people themselves may rebel against the knowers, the classifiers, the science that classifies them. Such interactions may lead to changes in the people who are classified, and hence in what is known about them” (239)

I think he connects this pretty closely with the idea of “making up people” (6).

The following things said by students fit with these ideas, I believe:

- Several students mentioned something about language:

- The stigma associated with certain words and ideas can affect the way that mental health (and other) issues are handled by those affected

- The importance of language in both memory and history–we need to have a dialogue before these two things can exist, and the particular words used can affect memory and history (e.g., the discussion of the development of “child abuse”)

- Language fundamentally shapes and alters thought and identity–people labelled/identified will (even if unconsciously) conform to some degree to the stereotypes/shades of connotation of that label

- How the looping effect works with multiple personality and other medical/psychological concerns:

- Multiple personality and other “disorders” (note: a word Hacking says he doesn’t want to use (17)) are not completely detached from culture and society, but change with these. The way we classify and talk about a disease can change the actual disease itself.

- Throughout history, different clinical paradigms were created when clinicians were trying to interpret and label some kind of illness. Our understanding is therefore a continuum and can change over time.

- We define ourselves based on what others think of us–for instance, Félida thought of herself as “double consciousness” because that is what her doctor thought she was.

- similar: People’s impressionability is a key in our personalities and physical development as we see ourselves as we are defined (or we reject the descriptions). This also works with the increase of the average number of alters.

- The way we are perceived and treated by others has such a profound effect that it can even cause physiological changes in brain chemistry and result in medical conditions

- We are not responsible for who we become, OR possibly that we are?

- People create, and follow, their own biographies (218). The soul or “biography” is constantly changing depending on others’ views and opinions.

- Fact and fiction are interrelated (see Hacking 232-233, e.g.); (Christina’s elaboration of what this might mean:) our identities are a mixture of facts and the stories we tell about these (e.g., the reference to the idea of stars vs constellations in lecture–there are stars, but how we put those together into constellations is “fictional”)

Memory, self-identity, making up ourselves

- Self-identity and personality are defined and created by our memories

- similar: People are defined and shaped by their memories, no matter how true those memories are

- similar: Memories play a key role in the development of a person (with either real memories or fabricated ones)

- (Christina: I think this is similar) Recalling past memories creates a new present reality; the past constantly affects the present as it is relived

- If our memory is what shapes our soul–who we are–then by changing our interpretation of the past, we also change who we are

- His arguments about the “indeterminacy of the past” and “action under a description” (chpt. 17) are relevant here: using new descriptions for actions from the past can lead to us becoming new persons, in a way (68), with new pasts and therefore new identities

- The way we remember things can be altered and memories can be created or repressed

- External forces are at play when creating the self–politically influenced memory

- similar: the recreation of memory is often influenced from outside with political views and agendas

- He raises concerns about the manipulation of memory in regards to multiple personality and remembering child abuse

- Memory and recollection in general are not by any means objective; rather, the passage of time in human history, including the turning of memory into a science, has seen attitudes towards and beliefs about memories change

History, historical contingency

- Challenging our perception of facts that we see as absolute; part of his history of multiplicity is made to show how our “general knowledge” came into being and to show that it isn’t as absolute as we may believe it to be

- From lecture: Hacking illustrates that there are a lot of facts that we take to be obviously true but are only contingently true–they have not always been true, and they need not always be so in the future

Multiple personality

- Multiple personality is linked with how we conceive ourselves and with memory

- The association that many psychiatrists have raised of multiple personality and childhood abuse is not proven, so it is only a conjecture

- Multiple personality is a real condition now and cannot be written off (as it has in the past) though it is socially constructed

Secularizing/scientizing the soul

None of the students said this in what they wrote down, but he makes several points about this idea:

“My chief topic, toward the end of the book, will become the way in which a new science, a purported knowledge of memory, quite self-consciously was create in order to secularize the soul. Science had hitherto been excluded from study of the soul itself. The new sciences of memory came into being in order to conquer that resilient core of Western thought and practice” (5).

“I am preoccupied by attempts to scientize the soul through the study of memory” (6).

The sciences of memory “all emerged as surrogate sciences of the soul, empirical sciences, positive sciences that would provide new kinds of knowledge in terms of which to cure, help, and control the one aspect of human beings that had hitherto been outside science” (209).

His discussion of the history of the sciences of memory that developed in the 19th century fits here: he is describing how we have come to think of memory as the key to whatever it is that we might call “the soul” (which he defines on pp. 6 and 215). He talks about these sciences of memory mostly in Chpt. 14, but I think what he talks about in Chpts. 10-13 could also be part of the discussion of the sciences of memory.

Other points

- Ignorance, or overlooking some things, in our search for knowledge about mental health issues can lead to detrimental results; categorizing people under certain mental disorders can be dangerous

- We can “create” other persons within ourselves, whether it’s intentional or unintentional

- The soul/identity are transient–who we are shifts and changes over time

Putting this all together

How do these various arguments/emphases fit together? As one student put it when I also asked them for questions they have about the text: “What is this book really about? Multiple personality, the soul, memory?”

Here’s my take on how this might all fit together, but there are, I expect, other legitimate ways to connect it. Under each heading, below, I’ve tried to put in bold and a new colour some of the other categories from above, to show how they could fit with the heading.

1. Memory, the sciences of memory, scientizing the soul, historical contingency

- He starts the book by asking why memory has become so important in our lives. He says, “An astonishing variety of concerns are pulled in under that one heading: memory,” and asks, “why has it been essential to organize so many of our present projects in terms of memory?” (3).

- His history of the sciences of memory, including how memory was important in discussions of hysteria, double-consciousness and multiplicity, are, I think, a way to show that the way we think about memory is historically contingent–it has a particular history, which he is trying to trace, and it’s not necessary that we think this way, then or now or in the future.

- Memory has become something to study scientifically, whereas that wasn’t the case before the 19th century

- Things we used to talk about in terms of the soul, in terms of spiritual difficulties, are now talked about in terms of science and in particular sciences focused on memory (5, 197)

- Further, he argues on p. 260 that “Only with the advent of memoro-politics did memory become a surrogate for the soul,” and “Since memoro-politics has largely succeeded, we have come to think of ourselves, our character, and our souls as very much formed by our past.”

- This suggests that part of his point is to argue that our current thoughts about our selves, our identity, being so strongly connected to memory and the past are also historically contingent; we don’t have to think of ourselves this way, necessarily.

- The question above, of why we think of so many things in terms of memory, seems to be answered by him saying that memory, as a scientific way of thinking about the “soul,” has become, due to the particular history of the sciences of memory, a topic that encompasses many different things.

- How is multiple personality connected to these points?

- Hacking: “I hold that whatever made possible the most up-to-the-moment events in the little saga of multiple personality is strongly connected to fundamental and long-term aspects of the great field of knowledge about memory that emerged in the last half of the nineteenth century” (4).

- In other words, the way we talk about, understand, treat MP is importantly linked to the history of the sciences of memory.

- Hacking argues, for example, that in views of “double consciousness” in the English-speaking world, “there was virtually no interest in memory within the symptom language” (150), because “memory had not yet become an object of scientific knowledge” (155).

- It is with Azam’s discussion of Félida that we begin to see a link between double-consciousness and memory–specifically, with amnesia (170). He first treated her in 1858, but the sciences of memory weren’t yet in place; it was only in 1875-1876 that she fit into “the emerging sciences of memory” (160).

- Then the link between memory, amnesia and multiplicity was strengthened with the case of Louis Vivet (179, 181).

- Today, amnesia is critical to the diagnosis of multiplicity (or rather, dissociative identity disorder) (from lecture)

- This means that “multiple personality” is a historically and socially created category, but is not therefore “not real” (chapter 1).

2. Making up people/looping effect

- He uses his history of multiplicity to demonstrate the “looping effect”

- e.g., the patients who are described as multiples may begin to act according to the paradigm of what a “multiple” is like (or, don’t forget, they may not quite fit it and then a new description has to be created)

- The connection between memory and identity, how we can create ourselves differently by seeing the past differently, can be an example of the looping effect–see, e.g., second paragraph on p. 239.

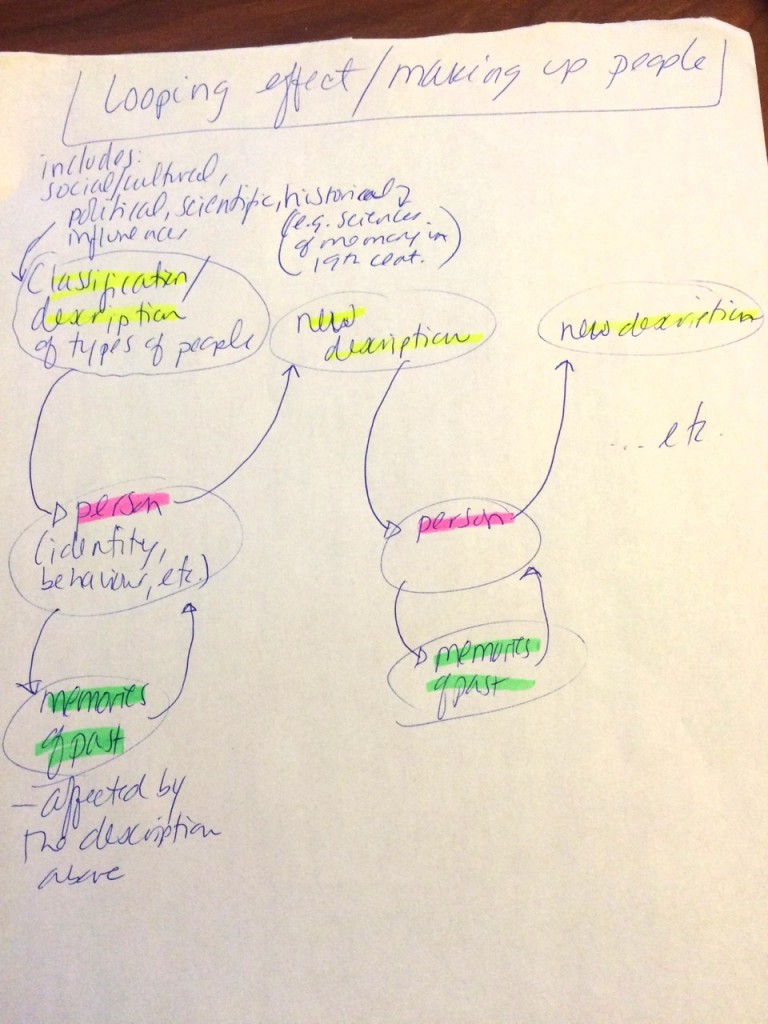

- so the “looping effect” can be both that

- descriptions from our social/cultural/scientific context can affect how we see ourselves (and our thoughts and behaviours also affect those descriptions)

- those descriptions affect how we see our past, our memories, and this also affects how we see ourselves

- so the “looping effect” can be both that

Here’s a picture of what I mean by these two aspects of the looping effect. (Sorry, I only have time to draw this up by hand right now!)

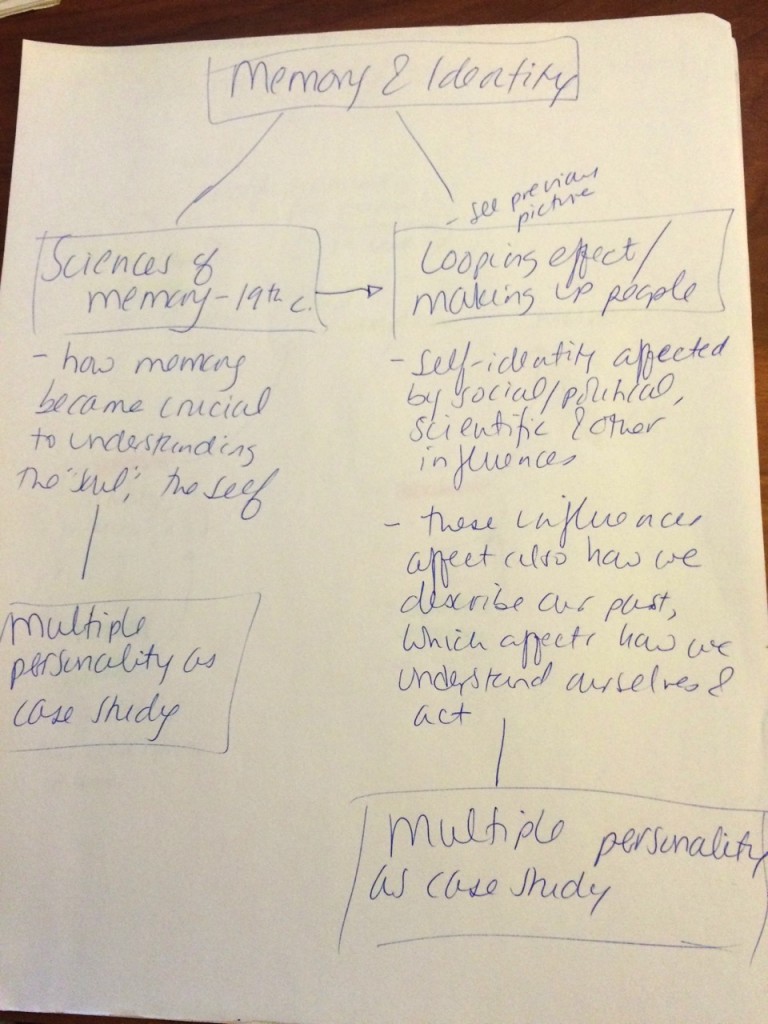

So what is this book about, then?

At this point, after working through all this, I think it’s about memory and identity, how the sciences of memory have developed such that we now see memory as an important part of our identity (that’s the point of the history of those sciences in the middle of the book). This is true for those diagnosed with multiple personality or dissociative identity disorder, but also true for all of us, as we change the past using new descriptions for actions from the past (chpt. 17). Multiple personality is used as a kind of microcosm for the larger phenomenon that we all experience, of how we think of memory as important to who we are, and how the looping effect also affects how we think of ourselves (and note from above, the looping effect also applies to current descriptions of us affecting how we see our past, and thus how we think of our identity.

Here’s another picture:

I don’t know if I’ve clarified anything for others, or just made things more complicated. I’ve done what I can in the time I have!