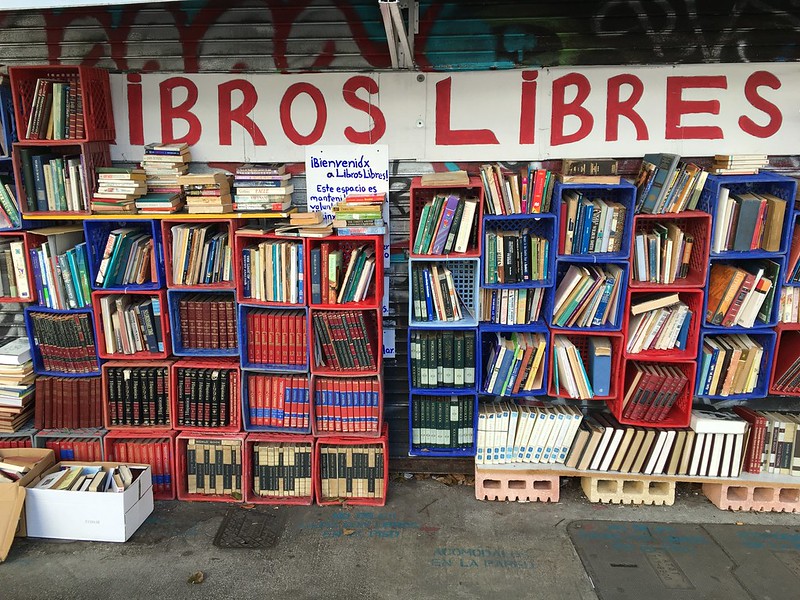

Libros Libres by Alan Levine on Flickr, licensed CC0.

In the last two posts I have been talking about Ruha Benjamin’s book Imagination: A Manifesto, which I’m reading as part of a book club for MYFest 2024. Here is part 1 on chapters 1 and 2, and here is part 2 on chapters 3 and 4. In this last post I’ll discuss chapters 5 and 6.

Among other things, chapter 5 focuses on how art and stories are crucial for changing imaginations and providing new visions. Benjamin quotes Angela Y. Davis:

… if we believe that revolutions are possible, then we have to be able to imagine different modes of being, different ways of existing in society, different social relations. In this sense art is crucial. Art is at the forefront of social change. Art often allows us to grasp what we cannot yet understand. (98-99)

For example, Benjamin points to artistic and imaginative dreams of what border areas between nations could be, rather than policed, surveilled, violent structures. One idea is a “binational library on the Mexico-US border” that would make the border “nothing more than a bookshelf allowing for ‘transnational exchanges of books, ideas, and knowledge'” (quoting Ronald Rael; 95). In a twist, Benjamin points out that such a library existed between the US and Canada in the early 20th century, and while that may not seem so far-fetched, if the former does then what does that tell us about the differences? About ourselves? Instead of the harsh break between ourselves and others, us and them, Benjamin states, “We must populate our imaginations with images and stories of our shared humanity of our interconnectedness, of our solidarity as people. A poetics of welcome, not walls” (p. 102).

Chapter 5 includes multiple examples of organizations dedicated to imagining the future, telling new stories about interconnection, collaboration, and interdependence, and working towards implementing them. Benjamin also dedicates space to discussing Afrofuturism and Indigenous futurism, as imaginations that counter a prevailing trend in which “Indigenous and racialized peoples, who know all too well what it means to live in a dystopian present, get suspended in time, never imagined among those peopling the future” (112).

I had heard these terms before but Benjamin’s short discussion helped me grasp them better. I have experienced that it is fairly common to think about Indigenous communities and cultures in terms of their past traditions, whereas Indigenous futurism, according to Grace Dillon, folds the past into the present, “which is folded into the future–a philosophical wormhole that renders the very definitions of time and space fluid in the imagination” (113). Benjamin points to the Initiative for Indigenous Futures at Concordia University here in Canada that, among other activities, teaches Indigenous youth how to “adapt stories from their community into experimental digital media,” to “envision themselves in the future while drawing from their heritage” (114). This is another form of breaking down walls, those between times as well as spaces, weaving the past into the present into the future and back.

My own visions of the future will of course draw from my past and present experiences, which will be limited (as any individual’s would be) and based in my privileged position. One thing I’m taking from these chapters is that imagining new worlds should be a collaborative activity with people involved who bring many different epistemologies, experiences, and identities.

This is a good segue into chapter 6, which is a short, practical chapter that provides sample activities to expand and strengthen imaginations. While Benjamin notes these can be done through individual reflections, she encourages readers to engage in these activities with others, through collective imagination: “Like mushrooms, the kind of imagination that can potentially transform toxic environments into habitable ones relies on a vast network of underground connections–with people, organizations, and histories” (p. 122). The appendix includes discussion- and activity-based prompts for individuals or groups that are short, but no less inviting and open-ended.

I am very grateful for the opportunity in MYFest to join a reading circle about this book, and not only reflect on imagination through reading the book, but also practice it in our group meetings. One activity I found particularly engaging (among many!) during the group meetings I was able to attend was a collaborative story-building activity. We started with a scenario, and then one person would have to brainstorm a challenge or obstacle, and another person would come up with an idea for how to address that, and then there would be another challenge, and so on, until we brought the story to a conclusion. These were short exercises, just a few back-and-forths of a challenge plus addressing that, but it was incredibly powerful to have the chance to imagine both how things can go well and also the reality that there will be complexity and obstacles, and then be nudged to really think hard about how to address those. This was a very hopeful exercise, in that we didn’t get stuck with the obstacles, but moved through and beyond them to something new.

There have been a few sessions in MYFest on imagination and speculative futures, including one that happened today on Imagination as a Liberatory Practice with Jasmine Roberts-Crews. During this session participants were encouraged to reflect on their practices of dreaming and play, and if those were challenging, to then reflect on why and what the obstacles are. I found myself thinking that I don’t have much of a dreaming practice, partly because I’ve been so influenced by the idea that such things aren’t “productive,” and it’s better to spend one’s time doing work that is more traditionally considered so. Of course, if I were someone involved in more creative pursuits I might feel differently!

Through reading Benjamin’s book and discussing it in the reading circle meetings, as well as attending Jasmine’s session (and others noted below), I’m realizing the deep importance of dreaming, daydreaming, imagination, and play to ideating and working towards necessary social change. Otherwise it’s too easy to get caught in how things are, adhering to existing practices and values and their notion of what counts as important and “productive.”

There have been several sessions so far (and more to come!) on imagination and speculative ideation, and I haven’t been able to attend them all. Thankfully, many have been recorded. You can find recordings of MYFest sessions on the MYFest website. For example, I attended the first session of by Dani Dilkes on Speculative Futures for Education, and am looking forward to reviewing the recording for the second (Session 1 and Session 2). Though I will not be in town and not able to attend, there is one coming up July 31 on Future Dreaming Part 2: Storytelling for Liberatory Education. The Wisdom of Fools Storytelling Activities and Readers Theatre are also wonderful examples of tending to our imaginations.

I am so grateful for the MYFest facilitators and the community generally for many things we’re learning together, including focusing on the importance of imagination, dreaming, and play in our lives and in our work as educators!