Not sure if this qualifies as an aspect of multimodality, but my readings over the Thanksgiving weekend (when one would imagine I’d have plenty of time to get into them, seemed to be actively working against me, conspiring with other events to make it nearly impossible to have them all read by Tuesday’s class! Dinner on Sunday evening was the least of my concerns, but my wife cutting her finger while preparing a salmon the next day, her trip to emergency to get stitches and then another trip to recover from the anaesthetic-induced nausea from the first trip all ended up with me at 2 am in the hospital waiting room, trying to read Pippa Stein’s wonkily scanned article on my low-battery iPhone – can any of this be blamed on the new basics?!

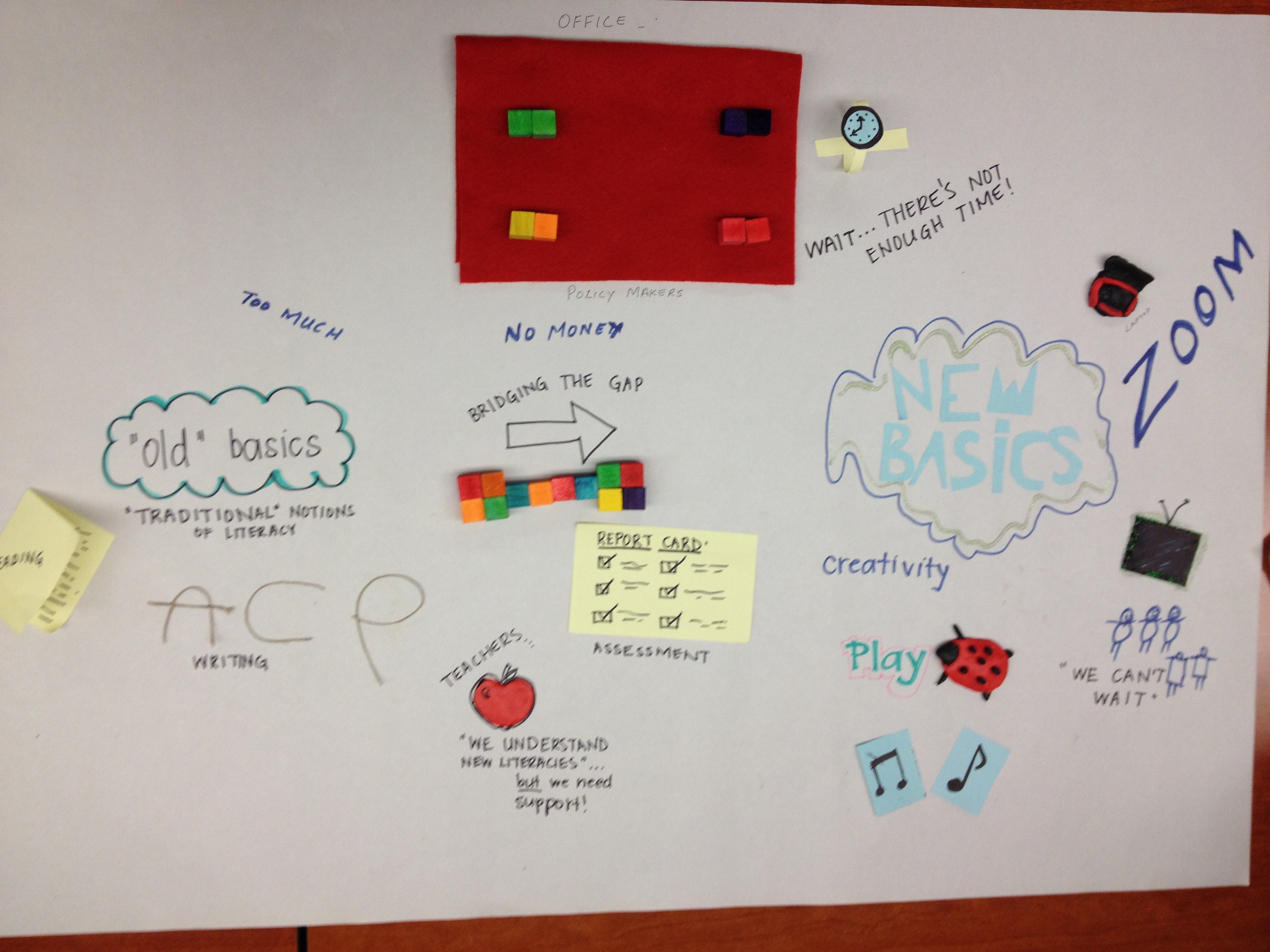

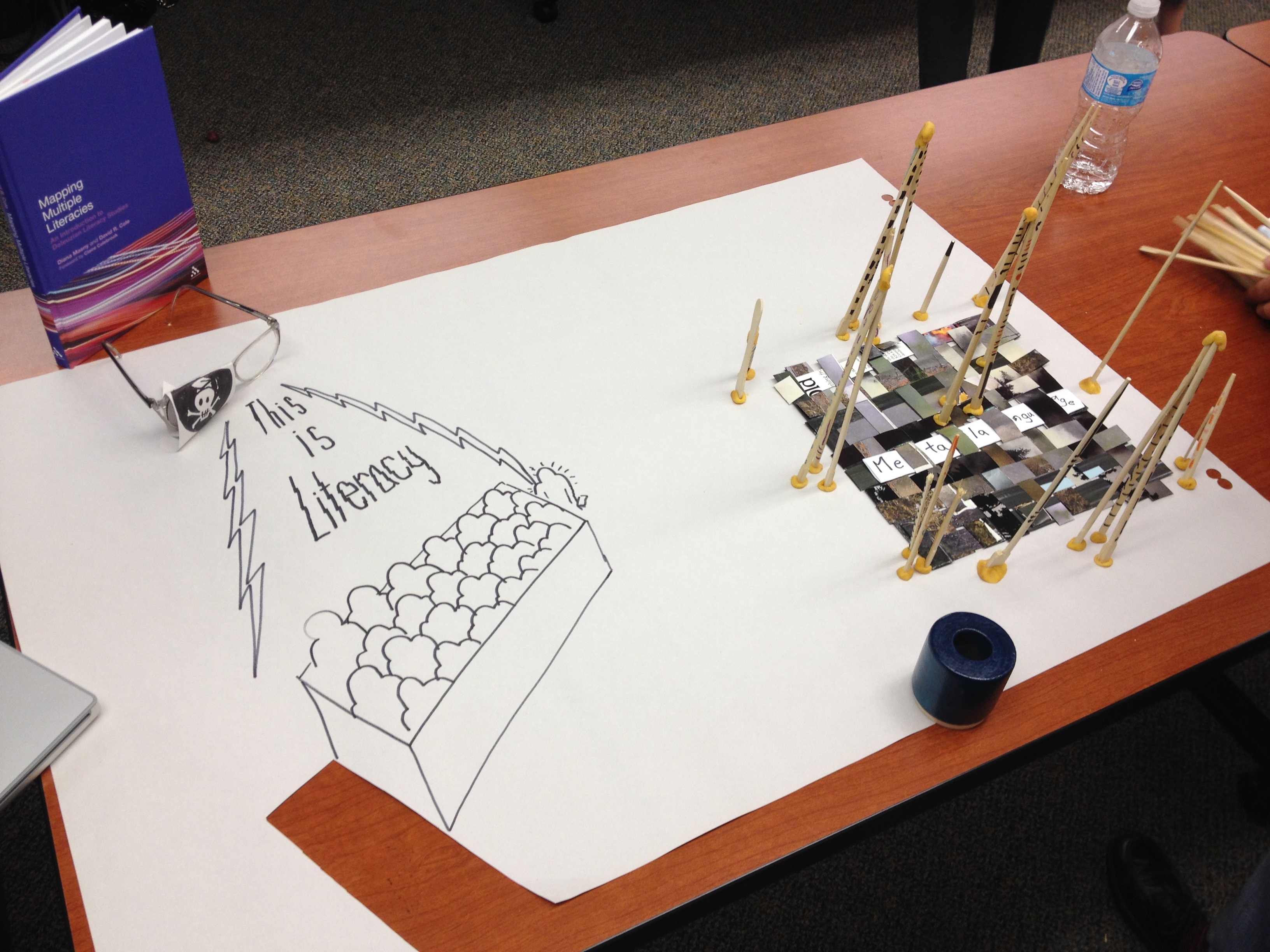

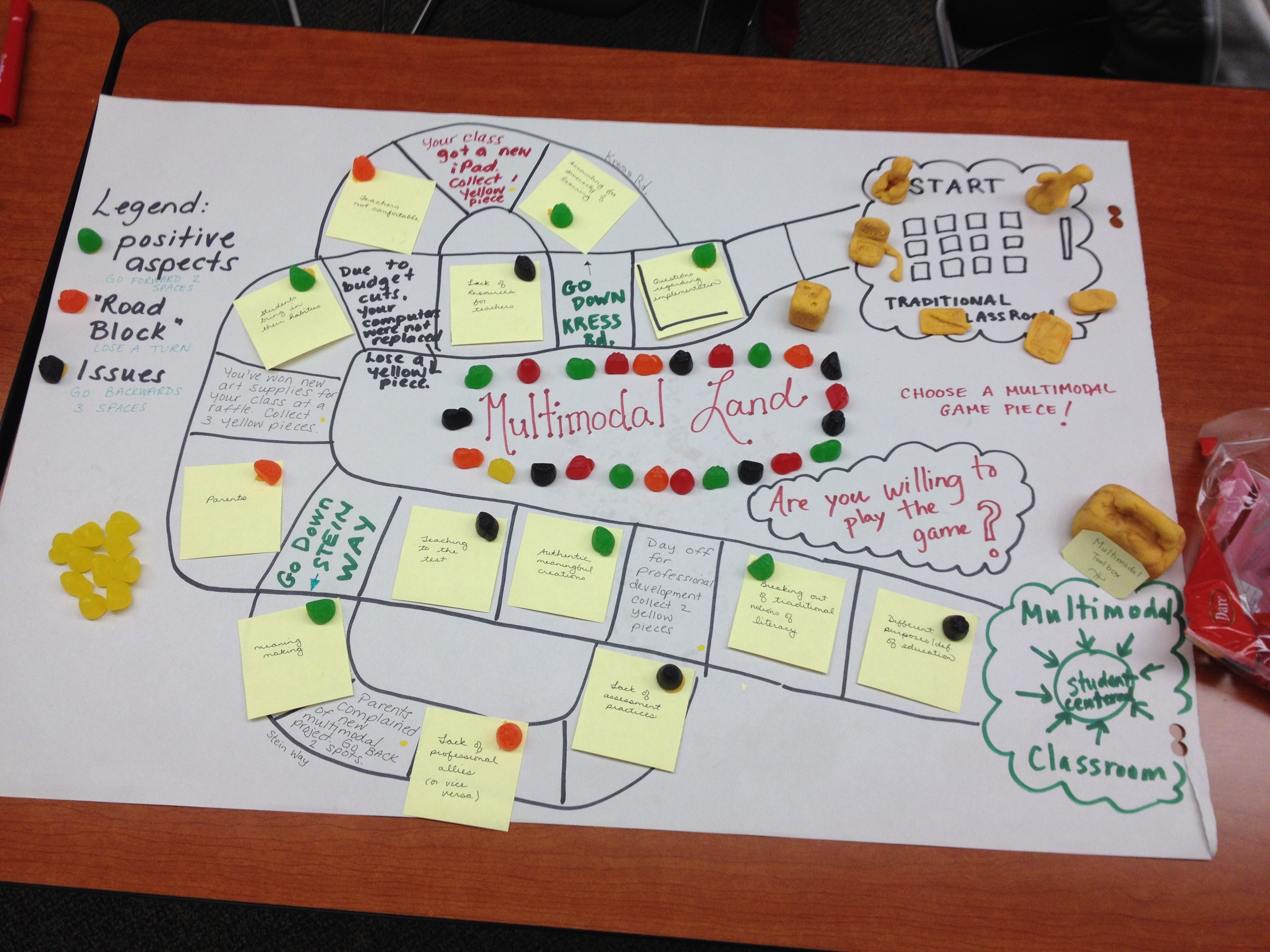

Stein’s trip to museum is a good place to start, not only because it was the most legible part of the PDF, but also for connecting back to an earlier class discussion where Anna explained an exhibit that was a slab of marble that every day had milk poured onto it. Her point was that the museum had taken down the title cards, and there was no explanation for what the artist attempted to achieve. While such a curious, innocuous artwork would not have captured my attention (unless a sudden draft caused the milk to ripple, it would have had me transfixed), I agree with the museum’s decision to remove title cards, PDA and any other multimodal method of filling in the gap created by an artist like Frida Kahlo between her biography and the paintings themselves. Nothing against Frida herself, the bio-pic directed by Julie Taymor completely won me over, but if her artwork needs description and commentary by people she would not have met, perhaps the artwork itself is not doing its job. It would be a good criteria for much of the new basics, our own class projects included in this post (sorry to Anna and Liam’s group, I did not get a photo of your fabulous projects), does it stand alone as an effective meaning-making object, or does there need to be another form of literacy to support what the teams created. Please feel free to leave a comment below on your interpretation of the three projects.

Anne Haas Dyson’s brief account of issues that occur with the new basics brings up another unanswerable question: how much of the students’ selves are acceptable to include in their literacy learning? Will it ever get to a point of being too much, and the students have to learn how to self-correct? In extreme cases where racist, sexist or other hurtful language is brought into the classroom, it becomes a stern lesson of what is not allowed. Yet in matters of faith, it becomes a matter of tactfully sidestepping theological issues that shape one person’s attitude. An example of this comes from my TOCing experience, where a class of grade 2/3’s had a guest speaker (called in by the principal to address some of the bullying and less-than friendly ways the students interact with other). The speaker was calm and professional, and wanted to get the class thinking about how nobody is more important than anyone else. This did not sit well with one student, who insisted several times that God is more important than anyone, and couldn’t accept the speaker’s gentle persuasion that it might be true for this student but not for everyone. What is an appropriate response? (Incidentally, the guest speaker told me confidentially that the students at this particular school – that will remain nameless on this blog – had the worst case of stubborn entitlement and it was difficult for any learning, social-emotional or educational, to happen at any grade level). Back to the role of religion in education, it is easy to wag fingers and say how reductionist most religions can be, the whole purpose of any religion is to promote one story while denying value in contradictory accounts. Dyson’s commentary on Tionna and Ezekial’s classroom discussion celebrates the identities these children have formed, and while it seems out of place to mention Jesus or God in an academic article, it is entirely relevant to a discussion on multimodality. It prompted me to ask a question in class that went unanswered: are churches on-side with multimodal education, or does it go against their belief system. Initial reaction might have one believe they would have nothing to do with new basics, but on second thought, Christianity has been multimodal for centuries: cathedrals, devotional song and poetry, and widely celebrated holidays like Easter and Christmas (for starters) are all inspired by words printed in the Bible. In fact, I would not be surprised to find an entire section of educational libraries with articles on religious multimodality.

Still there is the issue of basics, the traditional approaches to education mentioned in Marjorie Siegel’s earlier article that run contrary to new and new-fangled multimodal frameworks. Why are some people inevitably drawn back to them? With religion there is a purposeful “tying back” to one interpretation of text, but with schools shouldn’t the focus be on moving forward and developing? Her other article, from 2012, makes an evocative allusion to a fun Charles Dickens novel I recently read, Hard Times where the protagonist (or at least the character with the most dynamic change throughout the novel) is Thomas Gradgrind, a stanch uphold of traditions and the old basics. Books are book, numbers are numbers, and any attempt to make imaginative use of any school resource is frowned upon by this headmaster. What I have found interesting with this parody of extreme rationality is how it gets taken up by people who seem to be missing Dickens’ point. One of my side careers is working part-time at an afterschool academy, to train K-12 students on how to pass SAT and SSAT reading and writing tests – while they have no bearing on local schooling, many parents who want their children to get accepted into American universities will see this academy their children for rote learning skills. Of the many reading passages I have taught, and the usually inane multiple choice question that follow, passages that directly quote or refer to Hard Times seem to take the satire of education as well-reasoned persuasion. Why be critical of these passages, when students need to know only the correct answers to move ahead in life? The best I can do is suggest that students find time to read the novel, or at least watch the BBC adaptation, to get a better sense of how taking standardized tests is similar to being one of Gladgrind’s pupils, and that multimodality offers more than just “fact, facts, facts.”