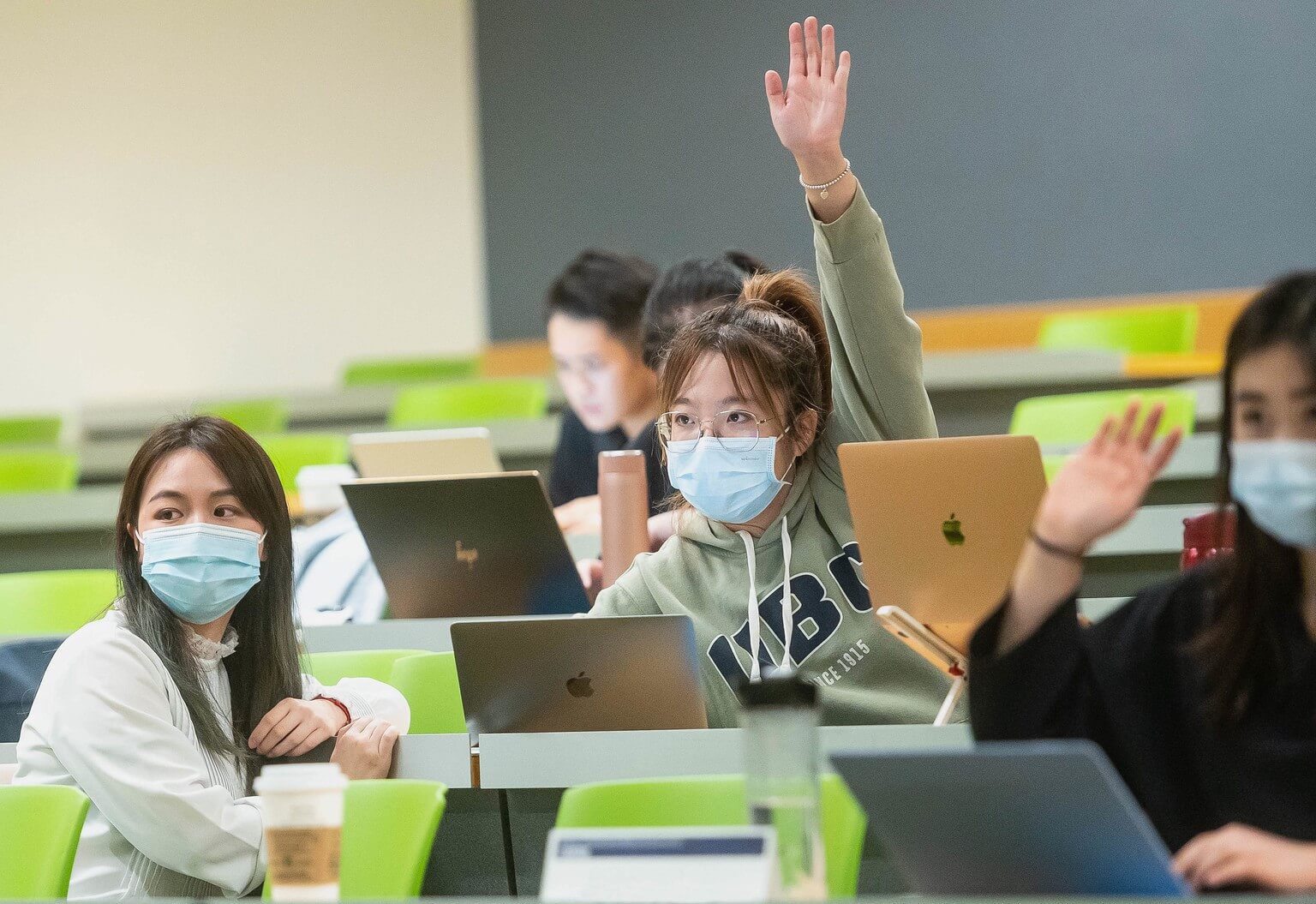

Walk into any undergraduate biology classroom, take a look around at the students in the room, and you might notice something: most students are women.*

Given that women now outnumber men in higher education throughout much of the Western world, this might not be too surprising, but it actually is quite different from what you would find in other STEM disciplines. While women make up about 57% of the student population in biology, they make up only about 20%, 33%, and 39% of the student population in physics, computer science, and chemistry, respectively (Perreault et al., 2018).

As the STEM discipline that is well-known for having more women than men, it might seem like gender is not an issue in biology. But underneath women’s numerical dominance lie some very serious gender-based disparities. For example, studies have shown that in biology classrooms:

-

- Women consistently ask and answer fewer questions than men (Eddy et al. 2014; Aguillon et al., 2020; Bailey et al., 2020).

- Women are less comfortable speaking out in class and are more fearful of being judged than men (Eddy et al., 2015; Nadile et al., 2021).

- Women underestimate their own understanding and abilities, while men overestimate their own understanding and abilities (Cooper et al., 2018).

- Men discount the knowledge and competence of women and overrate the knowledge and competence of other men (Grunspan et al., 2016; Bloodhart et al., 2020).

- Women tend to underperform on exams compared with men with similar grade point averages (Eddy et al., 2014).

These studies shine a light on how inequities can hide in plain sight. At first glance, it might seem like biology has overcome the gender issues that are so prevalent and obvious in other STEM disciplines. But despite their larger numbers, women are still being disadvantaged in ways that negatively impact their participation and performance. In other words, gender inequity problems are still there in biology, they’re just harder to see.

To be clear, the disparities listed above are not due to any intrinsic deficiencies in women; rather, they are the result of the historical, social, structural, interpersonal, and internalized sexism and discrimination that women continually experience—including within the biology classroom itself (Fisher et al., 2020).

But the numbers are undeniable. While originally developed by, and for men, the demographics have changed and biology is now a women-serving discipline. It’s time for us to acknowledge this distinction and ensure that we are teaching in a way that serves the women in our courses and does not perpetuate the disadvantages that have historically been put on them.

So, how can we better serve women in the biology classroom?

In my research into this question, I’ve identified five key strategies that have been shown to support women and promote their participation and performance in biology courses. What’s great about these strategies is that they not only support and uplift women, but in most cases, they also improve the learning environment for students from other marginalized and historically excluded identities, such as students who are IBPOC, 2SLGBTQIA+, and the first in their families to attend university.

Following are five evidence-based ways to create women-serving biology classrooms:

Counteract unconscious biases against women

We live in a society with deeply embedded gender roles (e.g., women are caregivers), stereotypes (e.g., science is for men), and socialization (e.g., women are to be deferential to men). These underlying gender norms not only interfere with how women perceive themselves, their abilities, and their sense of belonging, but can also impact how they are seen and treated by others, such as by peers and instructors (Eddy and Brownell, 2016). For example, male students tend to underestimate the knowledge and competence of their female classmates (Grunspan et al., 2016; Bloodhart et al., 2020), and faculty have been shown to harbor implicit bias against women, viewing them as less competent and worthy of attention (Moss-Racusin et al., 2012).

Because we live in a highly-gendered society, we likely all carry our own unconscious gender-based biases; but the good news is that there are things we can do to become aware of and counteract them.

First, start paying attention to gender dynamics and inequities in your classroom (Tanner 2009):

-

- Whose voices are being heard/not heard?

- Does one gender tend to receive more attention, praise, feedback, or help?

- Is one gender struggling more than another?

- Are the examples that you use in your class skewed to one gender (e.g., scientists, names, images)?

If you need help assessing these things, ask a trusted colleague or friend to observe your classes or review your course materials and provide you with feedback on any gender imbalances.

This first step is important, because once you can see the inequities, then it becomes easier to address and counter them. For instance, if you notice that your course materials skew towards showcasing men, you can intentionally increase the representation of women through things like Scientist Spotlights, guest speakers, and images of women on lecture slides. Be sure to include women with diverse intersecting identities, characteristics, and life experiences. This will help your students to see women – all types of women – as “science people,” and will also show them that you do too.

Additionally, you can explicitly talk about the historical and present discrimination against women in science to help students become more aware of systemic biases against women and what the impacts and consequences are, particularly for women who hold additional marginalized identities (e.g., IBPOC, 2SLGBTQIA+, disability, etc.).

More generally, having a course diversity and inclusion statement can set the tone for an inclusive and respectful classroom environment, and can signal that any instances of bias or discrimination will not be tolerated. This statement can be shared in the course syllabus, on the Canvas site, and during the first day of class. You may also want to create classroom guidelines with students at the beginning of the term to establish clear expectations for what is considered appropriate language and behaviour.

Finally, if you experience any instances of bias against women or any other marginalized groups in your classroom (e.g., language that puts women down), take steps to address it either in the moment or as soon as possible. You can find some advice and guidance for responding to biased language in this resource.

Provide opportunities for students to work together in small groups

Class size matters for women, as they tend to participate more and perform better in smaller-sized classes (Ballen et al., 2018; Ballen et al., 2019; Odom et al., 2021). While you may not have control over the number of students in your course, you can make the class feel smaller by allowing students to work in small groups. In fact, group work has been shown to help reduce the negative effects of a large class size on female students’ participation (Eddy et al., 2015; Ballen et al. 2019).

Group work sets up opportunities for active learning experiences, which have been shown to especially improve performance of women. Engaging in collaborative learning activities with peers also allows students to build confidence in their understanding and abilities, earn non-exam points, and develop a support network and sense of belonging, all of which are particularly important for women (Odom et al., 2021).

However, not all group work is created equal, and it is important to intentionally set up group work experiences so that they serve women rather than exacerbate any disadvantages women might already face. For example, women are more likely to value and participate in group work if they feel comfortable with the people they are working with (Eddy et al., 2015), so allowing students to choose their own group mates or encouraging them to build relationships with group members through icebreakers or sustained group work experiences could preferentially benefit women. If you do assign students to groups, ensure that women are not being singled out or marginalized in their group.

Women also benefit from efforts to encourage equity of participation among all group members. Women tend to prefer taking on a more collaborative role when working in groups and are more likely to participate in a group if they understand their role (Eddy et al., 2015). Structuring group work so that students each take on a defined role can help to establish clarity of roles and interdependence of group members, empowering women to participate and contribute. It could also be helpful to allow students to develop guidelines for group work (e.g., group contracts) and to designate an equity monitor in each group whose job it is to ensure that everyone’s voice is heard.

Reduce the impact of high-stakes exams on course grade

Women tend to experience more test anxiety and have lower confidence in their ability to succeed, which negatively impacts their ability to think and perform when taking traditional exams (Ballen et al., 2017; England et al., 2019; Cotner et al., 2020; Stang et al., 2021, Farrar et al., 2023). It’s no wonder, then, that women tend to do worse on exams compared to men with similar grade point averages (Eddy et al., 2014), and that they earn higher grades in courses that have less reliance on high-stakes exams (Odom et al., 2021). Because exams disadvantage women, using more non-exam assessments and reducing the stress-inducing aspects of exams can help to level the playing field and allow women to more accurately demonstrate their learning (Cotner and Ballen, 2017).

You can reduce the impact of high-stakes exams in a number of ways. One option is by decreasing the weight of exams on overall course grade and adding in other grade components (e.g., in-class assignments, homework). You can also make exams feel less stressful/high-stakes by allowing students to retake exams or correct missed answers, incorporating a collaborative aspect (e.g., two-stage exams), giving students more time (e.g., take-home exams), or breaking up larger exams into smaller pieces (e.g., weekly quizzes instead of a single midterm).

Additionally, you can have students demonstrate their learning in other ways, such as through presentations, projects, and reflections. These types of assessment strategies often provide students with more space and time to prepare, helping students to feel more in control of their performance and reducing their anxiety. They also usually allow for more personalization and choice (e.g., topic, format), which can increase student interest and engagement. If you’re looking for ideas for alternative assessment strategies, check out this guide.

Finally, given that each student has their own unique learning strengths, preferences, and situations, consider providing students with choice in how they want to be assessed. For example, you can offer multiple grading schemes that emphasize different components of the grade (e.g., different weightings for exams, homework, in-class activities, etc.). You can also offer students multiple types of assessments and let them decide which they want to complete. You may find that some students prefer taking a high-stakes exam, while others may prefer doing a project or writing a paper. Giving them the opportunity to choose what is best for them can help to ensure that they are being assessed fairly.

Encourage women to speak during class

Whenever I observe a biology classroom, I always start off by doing one thing. I make a little chart where I track the number of questions that are asked and answered by students based on my perception of their gender.* Almost without fail, the same pattern shows up each time: although women outnumber men in the classroom, men ask and answer more questions during class than women. And it’s not just limited to the classrooms that I’ve observed, the literature is actually quite clear that women’s voices are consistently underrepresented in biology classrooms (Eddy et al., 2014).

This is a problem because not only does it impact how women are participating in class, it also contributes to the inaccurate perceptions that women are not as competent or knowledgeable as men, both of which can negatively affect women’s performance and sense of belonging in the course. However, there are things that you can do to empower and encourage women to make their voices heard.

First, it is important to set up a classroom environment that promotes psychological safety and empowers students to share their ideas and take risks without feeling insecure or afraid of being judged. This will disproportionately benefit women, as women tend to experience a greater fear of judgment by others, preventing them from speaking up in class (Nadile et al., 2021). If you are looking for ways to promote psychological safety in your classroom, you can find some strategies in this short article.

Another way to hear more women speak is by using random call to solicit answers, rather than merely calling on the students that voluntarily raise their hands (who tend to be men). However, while random call can increase the diversity of voices being heard in the classroom, it can also cause anxiety (Cooper et al., 2018), especially for women who might already be more fearful about speaking up in class. One way of mitigating this negative aspect is to use warm-calling, in which students are given time to think about and prepare their answers by writing them down and/or discussing them with others in small groups before being called on.

If you don’t feel comfortable with warm-calling, know that women are more likely to voluntarily answer questions if they are first given an opportunity to engage in small-group discussions about them (Ballen et al., 2019). So, rather than soliciting answers to a question immediately after you pose it, consider posing the question and then allowing students to discuss the question within small groups. This will give them time to think and to practice sharing their thoughts with others in a less threatening environment so that they can build confidence in their answer before sharing it with the larger class.

Finally, women are more likely to speak up in class after hearing another woman speak, so employing these strategies early in the course or class session may serve to increase their impact on women’s participation.

Link course content to societal applications

Men and women have been shown to differ in their interests and motivation to learn biology. In general, women tend to more place more value in communal goals, such as helping people and solving societal problems (Eddy and Brownell, 2016). Therefore, presenting course content within the context of how it applies to and impacts society can preferentially benefit women students, particularly if the content is seen as helping to improve social conditions or address societal problems. And because interest in science has a greater impact on performance for women than for men (Ballen et al., 2017), tying course content to societal applications could also have a big impact on women’s academic achievement.

Including socially relevant topics in the course curriculum can also expose students to diverse scientists, helping to break down stereotypes of who belongs in science (Beatty et al., 2021; Metzger et al., 2023). If possible, try to use local examples, as they tend to be more immediately relevant and have been shown to have a greater impact on learning for women (Theobald et al., 2015). However, be aware that there may be some societal topics that are more uncomfortable to women than men, such as the bioethical topic of gene editing (Edwards et al., 2022).

Participating in research that addresses questions of social relevance is another way to link course content to societal applications and can also help students develop science identity, which can be especially important for women (Henter and Mel, 2016; Hanauer et al., 2022). One way to do this is through course-based undergraduate research experiences (CUREs) that investigate research questions relating to a social issue or problem, such as antibiotic resistance, food safety, or climate change. Allowing students to share their results with a real-world audience, such as with community members, politicians, or a government agency, can also help to align the research with communal goals, benefiting women.

In conclusion

Despite being the majority of students in biology classrooms, women are still subject to many internal and external factors that can negatively impact their participation, performance, and persistence within the discipline. To counteract the systemic and historical biases and inequities that women experience, it’s important to take steps to intentionally support women and create women-serving classroom environments.

The five strategies described above provide a broad, evidence-based approach to supporting women in biology classrooms, and many of them will also serve to support students with other marginalized identities. I encourage you to consider these five strategies and reflect on which ones you are already using and which ones you’d like to incorporate in your specific classroom context. Doing so will have a big impact on making your courses more equitable and fair for all.

*I acknowledge and recognize the following:

-

- Gender is not binary and in addition to women and men, other genders include non-binary, transgender, Two Spirit, gender non-conforming, agender, and gender fluid, among others.

- Gender is not the same as sex, and gender identity does not necessarily align with physical appearance or gender expression. Assuming someone’s gender based on their appearance can result in mis-gendering the person.

- Gender is just one aspect of a person’s identity and intersects with other personal identities and characteristics, such as race, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, first-generation college-going, etc., which result in unique experiences. Having additional marginalized identities can exacerbate the disadvantages experienced by women.

- Individuals vary in the degree to which they identify with their gender and adhere to gender norms. They also differ in how their gender identity influences their experience in specific settings, such as in a classroom.

- As a white, able-bodied, cisgender woman, I am limited in my understanding and perspective of gender and of the diverse range of experiences of women with different intersecting identities and characteristics.

Are there any other ways to support women in the biology classroom, or any strategies you’ve used that you’d like to share? Please include them in the comments below or send me an email—I’d love to hear them!