Pam Kalas, Maryam Moussavi and Solveig van Wersch recently worked with some colleagues to create two case studies that counter genetic essentialism and reflect the complex reality of how genes are expressed as phenotypic traits. These case studies, one featuring the variation in hair colour and the other featuring the variation in the blood clotting factor involved in Hemophilia A, introduce students to the many interacting factors that influence phenotypic variation in the context of real-world examples

Below, Pam, Maryam and Solveig share their motivation for creating these cases, how they did it, the impact it had on students and the course, and what they learned along the way.

What was your motivation for creating these case studies?

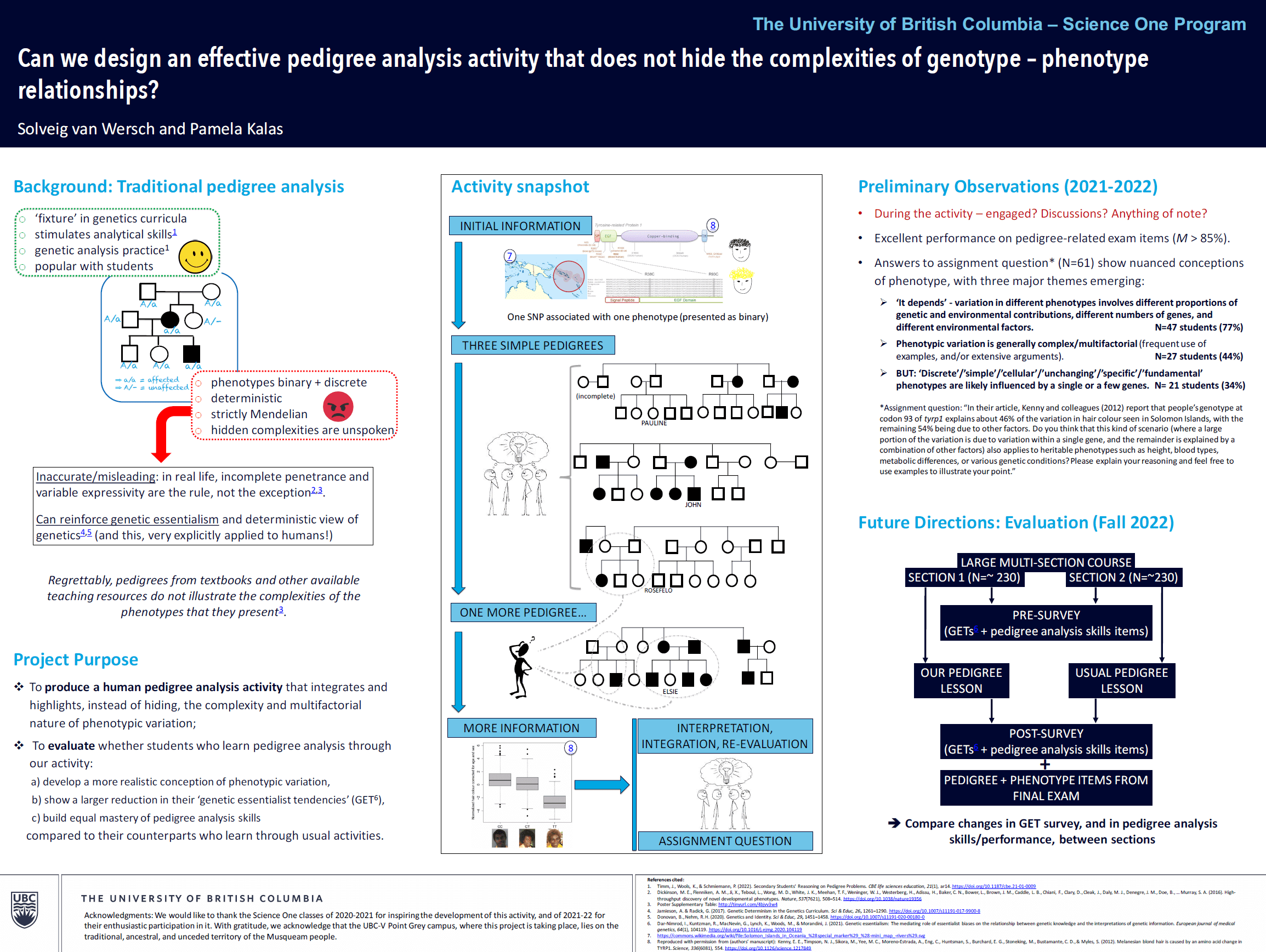

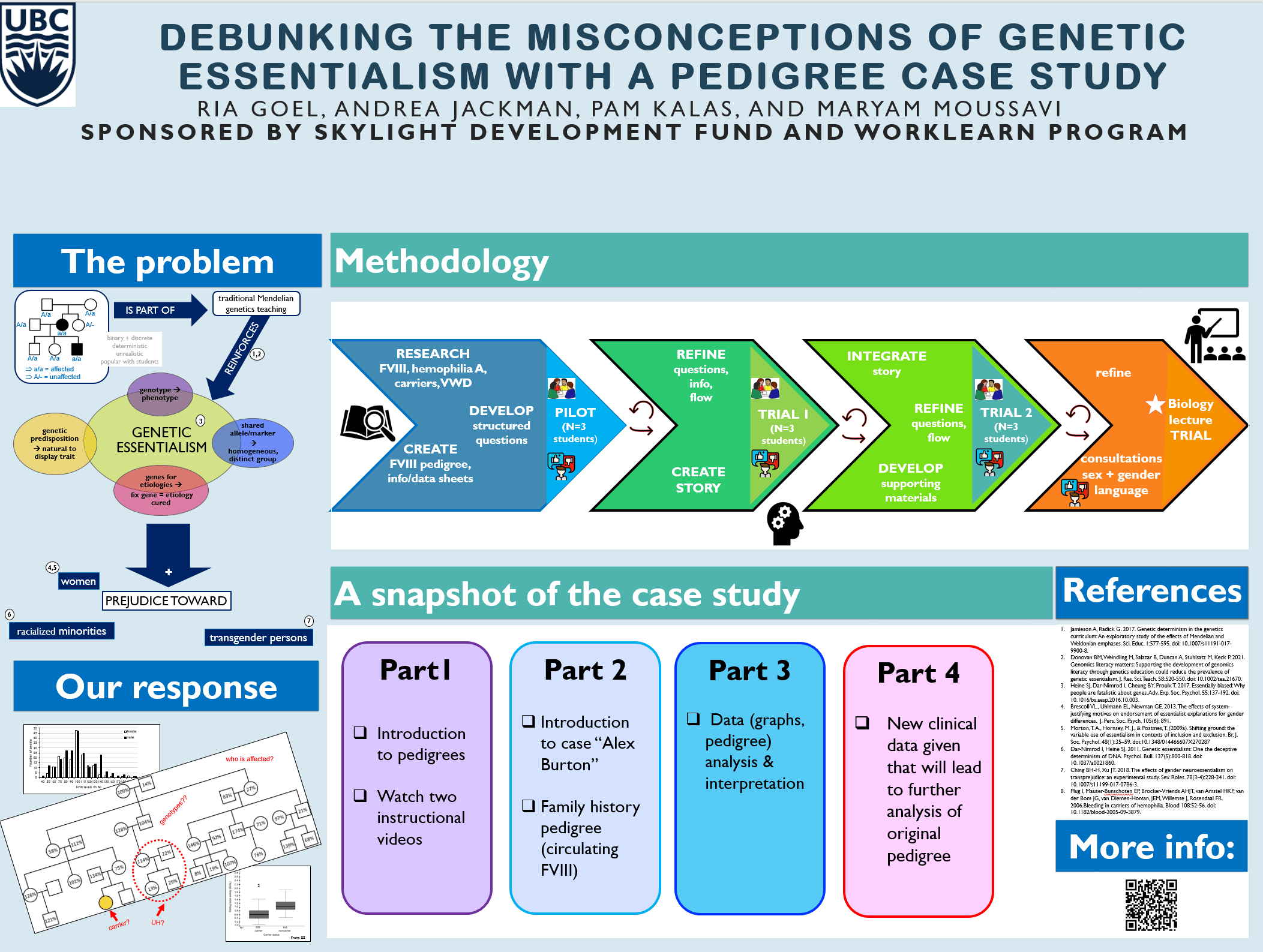

We wanted to create a lesson plan that would allow students to learn the basics of pedigree interpretation while also giving them a more realistic view of the phenotypic variation seen in humans, including for the Mendelian, monogenic traits typically used in these lessons. First year biology often lacks a quantitative element, so the integration of data examination/analysis in this case study allowed us to show students the realities of human genetics, particularly in regards to incomplete penetrance and variable expressivity. We also hope that by uncovering some of the complexities and consequences associated with categorizing individuals in a dichotomous manner, we can encourage students to challenge ideas and language associated with genetic essentialism.

How did you do it?

We used slightly different processes in creating the two cases, because of their different nature. For the hair colour case, the inspiration came from a single paper (Kenny et al., 2012) so there was no need for much additional research. After developing a set of questions that targeted our objectives, we designed a “story” to carry the case study and tried it out in class. We then used what we learned from that first trial to refine the lesson materials and improve its implementation.

For the blood clotting/hemophilia A one, the process of developing the case was much more complex because the case itself is more complex. Thanks to the support form Zoology, Botany, and Skylight, we were able to have two URAs (Andrea Jackman and Ria Goel) doing background research, developing materials, and developing the entire pedigree around which the case is designed. The URAs also lead multiple small-scale trials and focus groups with students; each time they reported back what they observed, what the students had said, and a set of suggestions, and we modified the case accordingly. We went through several iterations of this process, then our colleague and collaborator, Lynn Norman, allowed us to pilot the case in her class. We used what we learned from her students, and from our observations, to improve the lesson and implemented it again in one of our classes.

What was the result? What impact has it had on students or the course?

We were very excited to see that students responded enthusiastically in class, engaging in deep discussions surrounding the topic! The early exposure also resulted in some students being much more likely to consider variable expressivity in later class questions, forming reasonable (if unexpected) hypotheses.

What did you learn or find surprising?

The students’ enthusiasm and receptiveness to such a new and complex topic! We were surprised that the case study prompted some students to delve deeper than was asked of them. It was also interesting to see that once they were encouraged to think about it, many students already had a strong understanding of how traits, such as hair colour, can be affected by many factors, both genetic and environmental.

What challenges did you encounter?

It was definitely a challenge to keep it from ballooning into something too big! To keep the case studies focused and doable in one class, we tried to cut parts that, though fun and interesting, would have detracted from the lesson’s main purpose or tired out the students. And of course, as with most teaching materials, it’s hard not knowing if the case study was actually making a difference; we can see students’ reactions in class, and how they answer questions on assignments and exams, but does the lesson “stick”? Do students take it with them into their next course, and into their everyday life?

What advice would you give someone who wanted to create something similar for their course?

Here are some steps we suggest taking before jumping into creating a new case study:

- carefully look for what is already available (e.g. CourseSource, other QUBES resources, the NCCSTS, OER Commons, even textbooks sometimes)

- ask around, and see if you can modify or adapt something to suit your needs. Even if there is nothing quite like what you want, you will come across a lot of material that will inspire ideas and possibilities.

- learn about/read the literature on the phenotype that you want to focus on, and use real data. OMIM (https://www.omim.org/) is an excellent place to start.

Is there anything else you would like to share?

- Those who would like to try out our pedigree cases should contact us!

- Anyone interested in ready-to-use genetics lessons and activities (not just pedigrees!) that honour complexity and emphasize the role of environment in phenotypic variation should look into the work of Kelly Schmid at Cornell.

- Since a number of instructors have been working on using more inclusive and “neutral” language in biology classes, this paper comes in helpful when discussing human genetics.

- It is also a good idea to point out to students that, although our specific pedigrees depict fictitious people and families, many others do not – and we don’t always know if they are fictitious or real. So, we should keep in mind that the symbols we refer to in the pedigrees, such as “II-4” or “IV-1”, may represent real people who are someone’s siblings, parents, cousins, etc. and have real lives.