In Arts One last week, we read a number of texts by Freud, including “The Uncanny,” in which he discusses a short story by E.T.A. Hoffmann called “The Sandman.” Here’s a version of this short story, though it’s not the translation we read: http://germanstories.vcu.edu/hoffmann/sand_e.html

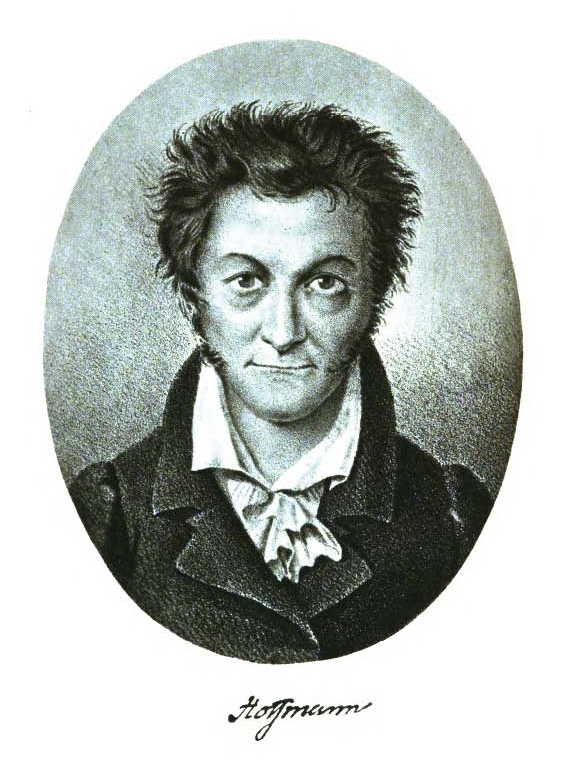

E.T.A. Hoffmann Self-portrait, public domain on Wikimedia Commons

We used the version of the story in this book: Five Great German Short Stories, ed. Stanley Appelbaum. Dover, 1993.

We didn’t get a chance to talk about this story much at all in our seminar meetings last week, having spent all of our time on the assigned texts by Freud. And I am so intrigued by Hoffmann’s story (and yet still pretty confused) that I thought I’d try to write my way through to possibly feeling like I have a better handle on an interpretation.

Our Arts One theme this year is “Seeing and Knowing,” and “The Sandman” fits into this theme quite well with its emphasis on eyes and vision. I can’t give a short synopsis here without more or less explaining the whole story, so I’ll just refer anyone who wants an overview of the plot to the Wikipedia page.

This post will be less a worked-out interpretation of the story than a series of observations that might be useful for others working out an interpretation (or me doing so later).

Clara and Olimpia

There are interesting parallels and contrasts between these two, I think.

Clara

Clara is presented in her letter, and by the narrator, as having “a very bright mind capable of subtle distinctions” (65). Her name suggests clarity as well. The narrator speaks of her eyes in glowing terms, saying that poets and musicians said of them, “Can we look at the girl without having miraculous heavenly voices and instruments beam at us from her eyes and penetrate our inmost recesses, awakening and stirring everything there?” (65).

- Not sure what to make of this, but this reminds me of how in Nathanael’s poem, Coppelius takes Clara’s eyes and throws them at his breast … (71).

Nathanael reacts badly to her “good common sense” (61), and accuses her brother Lothar of teaching her logic because he can’t imagine that she could be capable of such clear thinking otherwise; he tells Lothar to “let that go” (57)–yikes. What’s up with that? Nathanael doesn’t want an intelligent fiancée, perhaps?

Nathanael used to write stories that Clara would listen to and appreciate, but after the experience of Coppola coming into his life and reminding him of Coppelius, Nathanael’s stories become “gloomy, incomprehensible and formless,” as well as “boring,” and Clara no longer enjoyed listening. Nathanael starts to accuse her of being “cold” and “prosaic” (69), and then, after she tells him to throw his poem about they two and Coppelius into the first, he calls her a “damned lifeless automaton.”

Nathanael seems to think he is somehow expressing some deep poetic sensibility, seeing some real truths unavailable to “cold, prosaic people” (67, 69, 89). But to Clara his works have become prosaic themselves.

Olimpia

Jacquet-Droz Automata, by Wikimedia Commons user Rama, licensed CC BY-SA 2.0 France

It becomes clear pretty early on that Olimpia is an automaton. Hoffmann doesn’t try to hide this for very long, I think. Unlike Clara, she is described by others as “taxed with total mindlessness”; even Spalanzani calls her “witless” (87). Though Nathanael calls Clara a “lifeless automaton,” it is of course truly Olimpia who is such.

Yet Olimpia, unlike Clara, appears to list attentively to Nathanael’s creative works. Where Clara finds them “boring,” Olimpia is the best listener Nathanael has ever had (91). Where Nathanael thinks Clara is cold and unfeeling, he sees Olimpia as expressing deep and powerful feelings of love and longing.

Of course, Olimpia is not really feeling anything; these feelings are being projected onto her by Nathanael.

So we have:

| Clara | Olimpia |

| intelligent, bright, capable of subtle distinctions | witless |

| really loves N | incapable of love, but N thinks loves him |

| N thinks cold, unfeeling, prosaic | actually cold, unfeeling, but N thinks passionate |

| thinks N’s artworks dull, boring | doesn’t think anything about N’s art, but N thinks she loves it as much as he does |

Nathanael and Olimpia

There are hints throughout the text that Nathanael is or feels like an automaton:

- In his first letter, when he is recounting the frightening encounter with Coppelius in his father’s room, he says that after Coppelius threatens to steal his eyes, he started unscrewing his hands and feet and trying to put them in different places, speaking about the “mechanism” of these appendages. Coppelius puts them back where they were, saying,”The old man knew what he was doing!” (47). I’m still puzzling over who the “old man” here is (Spalanzani?)

- When Nathanael comes home to visit his family and friends (after the letters in the beginning of the story), he is gripped by the conviction that free will is an illusion, that “every person, under the delusion of acting freely, was merely being used in a cruel game by dark powers …” (67). To me, this suggests that he feels he is not in control, that someone else is controlling him as if he were an automaton.

- He even feels pulled to look at Olimpia through Coppola’s spyglass as if by “an irresistible force” (81)

It’s also pretty clear that when Nathanael falls in love with Olimpia, he is falling in love with a reflection of himself:

- When he looks at her for the first time through Coppola’s telescope, at first her eyes seem “strangely rigid and dead. But as he looked through the glass more and more keenly, moist moonbeams appeared to radiate from Olimpia’s eyes. It seemed that her power of vision had only now been ignited; her eyes shone with an ever livelier flame” (79).

- This sounds to me like it is only Nathanael’s looking at her that brings Olimpia’s eyes to life. She seems to be capable of vision only through the fact that he is looking at her and imputing that to her.

- Later there are some statements that make it obvious that Nathanael is seeing himself in Olimpia:

- N to O: “you profound spirit in which my entire being is reflected!” (85).

- N to Siegmund: “It was only for me that her loving looks grew bright, filling my mind and thoughts with radiance; only in Olimpia’s love do I find my own self again” (89).

- Then there is the very telling passage on p. 91, that makes it clear that when Nathanael thinks Olimpia is saying just what he would have said about his art, it must only be Nathanael’s own voice.

Finally, I find it interesting that when Nathanael touches Olimpia, she is at first ice cold, but then as he looks into her eyes she seems to warm up (83). There may be something here about Nathanael looking into her eyes, seeing himself, and then her skin seeming to pulse with life. He is bringing her to life with his looks and with his touches.

Some thoughts from all this so far:

- Nathanael doesn’t want Clara to be intelligent, doesn’t want her to see rationally and clearly into what is going on with him. She says that his fears are due to him allowing them to come to life, and he doesn’t want to hear it.

- Nathanael really loves a woman who has no mind at all, who sees nothing (literally), and who can therefore serve as a perfect mirror to Nathanael himself, reflecting himself back to him as his object of love.

Nathanael and the narrator

The narrator speaks of having an experience that you want desperately to communicate to others, but when you try, “[e]very word, … everything that human speech is capable of, seem[s] to you colourless, glacial and dead. You try and try, you stutter and stammer, and your friends’ sober questions blow upon your inward flame like icy blasts of wind until it almost goes out” (61). This struck me as descriptive of what Nathanael was trying to communicate to Lothar and Clara about Coppelius and Coppola, and his response to Clara’s “good sense” as thinking of it as cold and unfeeling. Nathanael struggles to express what he wants to express to Clara, and finally hits on the poem about he and Clara and Coppelius, which she eventually tells him to throw into the fire.

Similarly, the narrator him/herself says that Nathanael’s story had been so gripping that s/he struggled with how to begin. So, the narrator says, “I decided not to begin at all. Gentle reader, accept the three letters (which my friend Lothar kindly made available to me) as the outline of the picture, to which I shall now, while narrating, strive to add more and more color” (63). This is similar to how the narrator describes trying to tell others of a profound experience by first providing an outline and then later shading it in with colour. The letters are the outline that the narrator begins with, but Nathanael’s first letter is also the outline he begins with in telling his friends of his experience, and he tries to fill in the colour later.

So there is some kind of parallel being drawn here between Nathanael and the narrator of the story, I think, though I’m not sure what significance that might have.

Eyes!

Really, this whole story centres around eyes. And we have an essay topic students could write about, asking them to discuss the significance of eyes and vision in the story. I hope someone takes this up, because I’m still unsure myself. Here are some random thoughts.

- When Coppola/Coppelius takes Olimpia away and leaves her eyes, Spalanazani says to Nathanael that the eyes were “stolen from you” (95).

- This makes sense to me insofar as her eyes only came alive, only had the power to see, when he looks at her and sees her as having the power of vision. Her eyes are his eyes, in that sense.

- This also brings up the experience Nathanael had when he is spying on Coppelius and his father, and Coppelius catches him and threatens to take his eyes because they need some eyes (for some reason). He was going to steal Nathanael’s eyes, until his father begged Coppelius to let N keep them. What to make of this, though, I don’t yet know.

- In Nathanael’s poem, Coppelius takes Clara’s eyes and throws them at N’s chest, and they enter his chest “like bloody sparks, singeing and burning” (71). To me, this could suggest a fear of Clara really looking into his heart, that he doesn’t want that?

- Clara later says that Coppelius fooled him and she still had her eyes, that what entered his breast was drops of his own blood. But when he looks at Clara’s eyes it is death looking back (Olimpia’s eyes?). Perhaps it’s that he fears that if he really were to “belong to her” (71), and she were to really see into his heart, he would die.

- Notice that when Coppola/Coppelius takes Olimpia away, Spalanzani picks up her eyes from the floor and throws them at Nathanael’s chest, at which point he becomes mad: “Then madness seized Nathanael with red-hot claws and penetrated him, lacerating his mind and thoughts” (95). So the scene in N’s poem gets repeated here.

- In addition, Coppola’s spectacles scattered over the desk are “shooting their bloodred rays into [Nathanael’s] breast” (77)–another similar image.

- Finally, when Nathanael looks at Olimpia through the telescope at the party, her “loving look … pierced and inflamed his heart” (83).

- There is some connection between fire, heat and eyes that I can’t yet make sense of:

- There is the childhood scene where Coppelius and N’s father are working over the fire, and Coppelius calls for eyes; then Coppelius grabs N and threatens to put “red-hot grains” into his eyes (47).

- In N’s poem, Clara’s eyes singe and burn his breast when Coppelius throws them at him; similarly, when this scene is repeated and Spalanzani throw’s Olimpia’s eyes at N’s chest, then madness seized him “with red-hot claws” (95).

- When Olimpia’s eyes seem to come to life when N is looking at them through Coppola’s telescope, the power of vision is connected to fire: “It seemed that her power of vision had only now been ignited; her eyes shone with an ever livelier flame” (79).

- As noted above, Olimpia’s loving look “pierced and inflamed his heart” (83).

Well, that’s about as much rambling as I can do for today, and I really haven’t come to much in the way of conclusion yet. But perhaps these thoughts might be helpful for others in their own interpretations.