Each time I get a discourse of critical pedagogy in my hands, literally holding onto a book instead of an article or chapter reproduced on-line, I go to the index and see what names appear in the text. Listings of Gee, Vygotsky, Freire and Murray are good signs that parts of the book will be on somewhat familiar grounds, and every once in a while there are pleasant surprises, like a reference to Shakespeare or the Brontëe sisters will appear (very fortuitous that Dorothy Holland et al. has an entire section on Bakhtin and Vygotsky plus a brief allusion to Shakespeare!). One name I have noticed with increasing frequency is Sigmund Freud, and I can understand the connection between the present texts being read and the founder of modern psychoanalysis. Another name I would expect, yet rarely ever find, is the more radical former colleague of Freud, Carl Jung. This week’s readings put me in mind of this “other” psychologist and the brief outline of his beliefs I had read earlier this year. Understandably a controversial figure not to every scholar’s tastes, still some of the concepts he presents are a wealth of ideas to make connections with identity and culture. This is particularly true in connection to Gee’s interview describing how he got into critical discourse analysis (NB: all lower-case letters). Both Jung and Gee seem to be aware of the shifting positions one will have throughout one’s career, and even the occasional moments of synchronicity that leads to the Big Idea.

Jung: A Very Short Introduction by Anthony Stevens

Jung: A Very Short Introduction by Anthony Stevens

My rating: 4 of 5 stars

A just-right introduction to this series by Oxford University Press, although I was tempted to see if Greer’s VSI on Shakespeare would have anything new to say on an already familiar topic. Stevens’ Jung was fascinating, especially as his psychoanalysis is just one of the many brilliant insights into what seems like a vastly complex and some would say indecipherable mind like Jung’s. Not only will readers have a better sense of who they are, and what archetypal influences shape them into individualized Selfs, but we get peeks at the course Jung’s life took, narrated adequately in his own words based on his self-analysis. It will be hard now to get through any of Freud’s groundbreaking works, such as the Interpretation of Dreams without thinking of his eventual breaking off with Jung, as if Freud was only prepared to go so far. Jung seems to have no limits, especially when it come to making sense of a theories as dynamic and multidimensional as the collective unconscious, shadow and mythological influences. As Stevens mentions numerous times, Jung was never one to be tied to one theory, and throughout his long career, everything he thought and wrote would be open to re-evaluation. It is obvious the best way into understanding him more is to read his ideas, and Memories, Dreams, Reflections has sat in my bookcase unread for far too long, yet in a synchronistic way I hope to discover more about my own self more than Jung with reading his biography. I’m even tempted to visit a therapist to see how it all will work out, and I am pleased to learn that his patients were given the freedom to find their Self by their selves. View all my updates

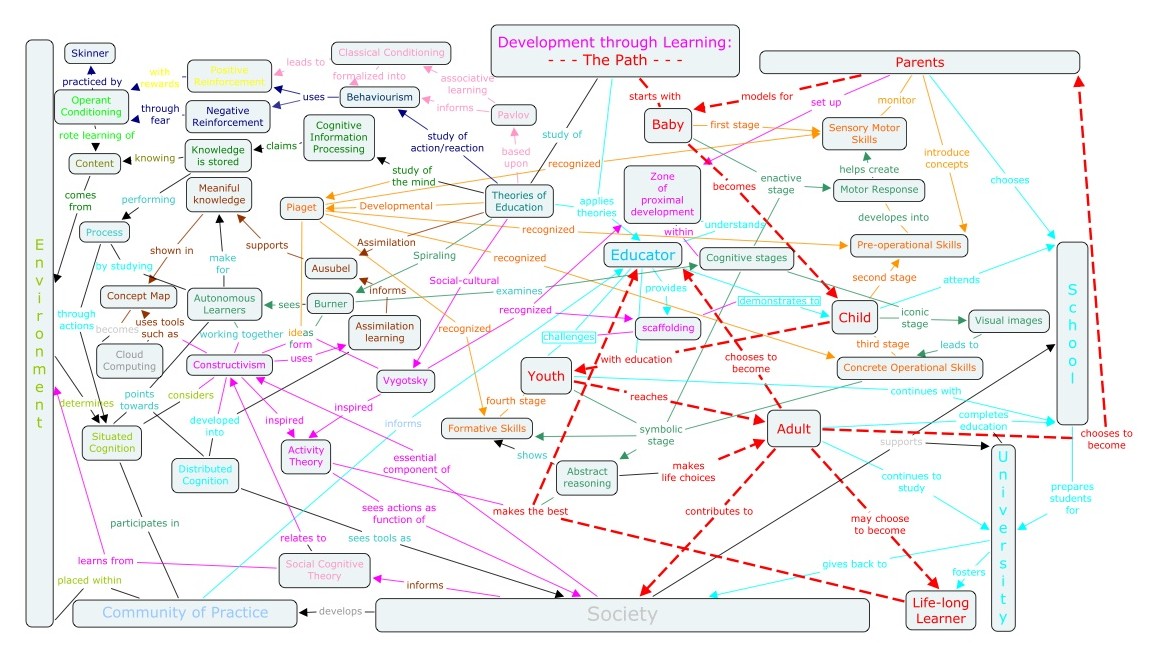

Like Jung, in some ways, Gee discusses at great length how he cobbled together his theories, almost as if he makes up his critical discourse analysis as he goes along. It may be a surprise to some classmates that he does acknowledge Mikhail Bakhtin twice in his interview, but not so much as the intellectual debt he owes the Russian literary theorist, rather how others should not be so beholden to the big ideas from the past. Instead, we get Gee’s surfing metaphor, making his discourse current for the Internet (and surfing) communities of practice: each scholar has to develop a sense of which wave to ride: join the established ones from the recent past like Kress and Fairclough and ride along, or wait for the next wave as Gee seems to be doing with video game literacy, or make some waves of one’s own. At some point in Jung’s career, he began to doubt most of what he had written before (perhaps fell prey to waves of criticism from the traditional Freudian analysis/surfers) and through this crisis produced even more astounding writing on alchemy, flying saucers and answers to questions raised by the Book of Job. Perhaps not as extreme as Jung (perhaps not yet in any case) Gee seems to be turning his back on the once-revolutionary multimodality theory of literacy, and can be seen by some as obsessing over video games. Yet he defends this choice by recalling how Sarah Michaels and Courtney Cazden’s critical analysis of sharing time radically changed the way educational researchers thought about this seemingly innocent primary grade ritual. Especially important topics as serious gamers are already making inroads towards academia. One last surfing analogy: in 2001 there was a documentary called Dogtown and the Z-Boys which showed the inception of skateboarding culture from the surfing community in Santa Monica. The Zephir team (Z-Boys) seemed just as surprised as anyone else that millions of dollars could be made from doing what most people saw as an idle pastime. Already in South Korea, there is a huge industry created around playing the on-line game StarCraft and perhaps a student’s Minecraft skills will be more in demand than an ability to spot names like Jung, Brontëe or Shakespeare in book indices.

Speaking of the index, what exactly is “indexicality” as mentioned in Davies and Harré’s article? Most of the way through this article, I found myself a bit too much in the deep end of discursive analysis, and this notion took me aback. Admittedly, there were moments of crystallization, particularly their example from Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina, reminding me of Jasper Fforde’s footnoter conversation on the same novel that appears (at the bottom of various pages) throughout The Well of Lost Plots. Anyhow, where was I? Near the end of their discussion on identity-makers, they examine Robert Munch’s Paper Bag Princess, very much an anti-Anna Karenina heroine, from a feminist perspective. Must have been disheartening for the researchers when the students reacted negatively to the active heroine, mostly those who see the poorly-dressed princess as “bad”. Seems particularly cruel as the story itself is designed to assert the heroine’s side of the story and change the hegemonic view that girls must patiently wait for the boys to restore order to the kingdom. I wasn’t a huge Munch fan when I was growing up (a bit before my time, actually) and while I can look back at the radical changes he set for the Once-upon-a-time crowd, at the time I only remember being peeved that boys were portrayed as dumb bullies. Now I am quite fond of children’s literature that pushes the boundaries and problematizes the hero’s journey – most of Fforde’s novels have women in the narrative driver’s seat. And to bring the discussion back to Jung, he opened the door not only for Joseph Campbell’s Hero with a Thousand Faces by working out his own archetypal images, but Jung also has interesting theories about dual masculine/feminine identies (animus and anima) that I need to explore further to see how they apply to literacy.

This brings me back to Dorothy Holland, and the first two chapters of Identity and Agency in Cultural Worlds. While Jung does not appear anywhere in this book, a shadow of anima theory seems to be lurking in chapter one with its evocative title “The Woman Who Climbed up the House” – both Campbell and Munch would have written something relating to Holland and Debra Skinner’s Nepalese field work. The pseudonymous Gyanumaya could not enter the rented house to be interviewed by Holland and Skinner, and her creative solution inspires Holland to write about how some people are positioned in society, and others resist the constraints placed by this positioning. At some point, it may have occurred to Gyanumaya that not being able to enter the house could have simply sent her home, her story never shared with the foreign researchers. It is not here, however, that we find out what she contributed to their study, other than the house-climbing incident; more details can be found, I assume in her 1992 New Directions in Psychological Anthropology article. She does, unlike Gee, have no problem directly referencing Bakhtin and Vygotsky, claiming to be standing on the shoulders of these socio-cultural giants – talk about being a head taller! I am very interest to read more of Holland et al. discourse, and may have some time during the December break to read their work while also starting in on Jung’s Memories, Dreams, Reflections.

Reference

Holland, D., Lachicotte, W. (Jr.), Skinner, D. and Cain, C. (1998). Identity and agency in cultured worlds. Cambridge: Harvard U P.

Holland, D. (1993). The woman who climbed up the house: Some limitations of schema theory. In Theodore Schwartz, Geoffrey White and Catherine Lutz (Eds.) New Directions in Psychological Anthropology. Cambridge: Cambridge U P. 68-81.

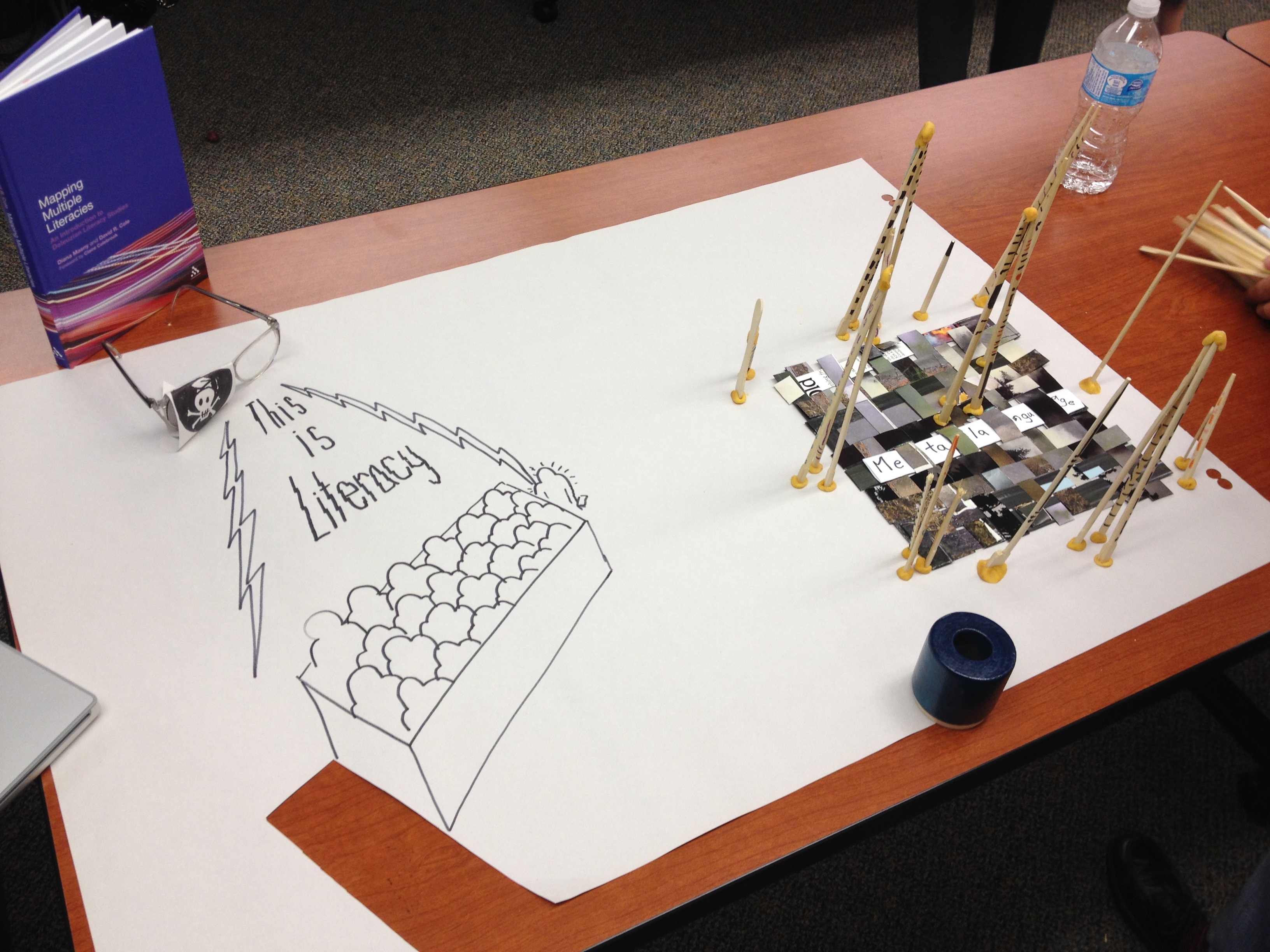

Mapping Multiple Literacies: An Introduction to Deleuzian Literacy Studies by Diana Masny

Mapping Multiple Literacies: An Introduction to Deleuzian Literacy Studies by Diana Masny